For all its relevance to their interests, I wonder how many menswear enthusiasts would, or could, sit down and read this book. Despite coming in the same thickness and glossiness as many standard menswear books do, The Men’s Fashion Reader has no dressing advice to offer, nor does it concentrate exclusively on the history, development, or mechanics of men’s clothing. It does contain a great deal of analysis, delivered in the form of 35 separate articles on everything from dandyism to the Japanese adoption of the western suit to the rise and fall of the Men’s Dress Reform Party. And indeed, any man who takes an active interest in what he wears will find dozens upon dozens of fascinating pages — embedded, alas, within hundreds of academic ones.

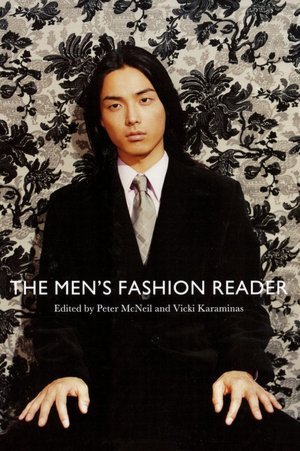

Here I use the word “academic” mostly by its neutral definition, “of or pertaining to a college, academy, school, or other educational institution, especially one for higher education,” but not without an eye toward the more pejorative ones. “Of purely theoretical or speculative interest,” “excessively concerned with intellectual matters and lacking experience of practical affairs” — these charges often stick. McNeil and Karaminas make no bones about their book as a product of the academy, for the academy, and a quick glance across online collage syllabi reveals that professors do indeed assign it. Yet its relatively lush printing, complete with two sections of color plates showing off eighteenth-century finery, midcentury California leisurewear, and the unconventional fashion choices of Japanese youth surely makes it one of those burdensomely expensive, beer money-eating pieces of required reading. A peculiar hybrid, this book: its form keeps it from quite belonging on the student’s bookshelf, and its content keeps it from quite belonging on the well-dressed man’s.

Several of its articles, to be fair, do supply just the kind of knowledge that even clothing-oriented fellows tend to lack. Many of them have a reasonable enough command of the evolution of menswear, though only back to the twenties or thirties, and mainly in the Anglosphere even then. Deep historical and wide cultural knowledge of men’s style being something of a rarity, the average reader would do well to spend time with The Men’s Fashion Reader’s first section, “A Brief History of Men’s Fashion,” which features such articles as John Harvey’s “From Black in Spain to Black in Shakespeare;” David Kuchta’s “The Three-Piece Suit,” which traces the seventeenth-century emergence of just that; and even Olga Vainshtein’s “Dandyism, Visual Games, and the Strategies of Representation,” which reveals a wealth of information on how nineteenth-century dress became twentieth-century dress through the framing device of opera glasses, lorgnettes, and other such vanished male accessories.

The book’s contributing professors, honorary associates, and fellows seem condemned by research specialization to write through these sorts of intellectual pinholes. Non-academics may find themselves put off by some of the article titles that result: “Consuming Masculinities: Style, Content, and Men’s Magazines,” “A Tale of Three Louis: Ambiguity, Masculinity, and the Bow Tie,” “American Denim: Blue Jeans and Their Multiple Layers of Meaning.” More legitimately frustrating are the frequent citations of high-profile theoreticians rendered unintelligible by decades of intellectual isolation in the academic humanities. I suspect little of it means anything to a man who simply wants to dress more consciously.

What a shame, since The Men’s Fashion Reader contains so many edifying stories of men dressing consciously. The flamboyant but (for his time) aesthetically chaste nineteenth-century dandy Beau Brummell makes several appearances, as he should. And we can all learn much from the book’s accounts of how certain style pressures operated in 1930s Oxford, of the choice men of the Meiji Restoration faced between traditional and Western dress, of industrialized tailoring permanently opening up sartorial options for all social classes, and even of the supposed “great masculine renunciation” of display and beauty in clothing. While some of the material reads rather bloodlessly, the book’s inclination toward gender studies actually contributes to some of its most immediately fascinating and illuminating sections, which examine the patterns in deliberate, visible male homosexual dress — the habitués of the Vince, John Stephens, and John Michael men’s shops of midcentury London; the mustachioed, work-shirted “Castro clone” of San Francisco; the one and only Liberace — before the widespread acceptance of male homosexuality itself. I can’t say the same of the readers my own professors made me buy.

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall. To buy The Men’s Fashion Reader, you can find the best prices at DealOz.