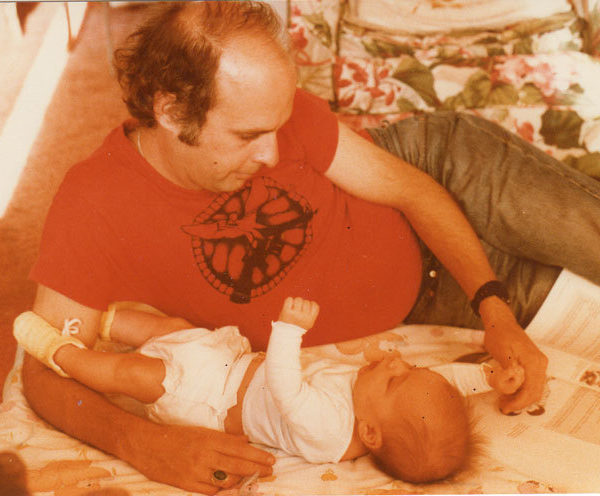

Recently Max Wastler of All Plaid Out asked me to write a brief piece about what I’d learned from my father. The result has almost nothing to do with clothes, but I thought I’d share it here. Above: my father and I in 1981.

My father was homeless when I was conceived. That’s something I found out recently.

I knew he’d been without a home and had even lived on the street a little, but I didn’t know that particular circumstance of my origin story. It’s true, though: In 1980, when my parents first met, he was a homeless alcoholic and drug user, suffering from severe post-traumatic stress disorder. You can see how maybe my parents’ marriage, which happened after the events of my conception, didn’t go well. In fact, it went about as poorly as a marriage without physical violence could possibly go. They divorced before I remember.

But my father isn’t the villain of this story. Far from it. He is the hero. This is a father’s day appreciation, after all.

Here’s the thing: my father grew up in an abusive home. He tried to escape by enlisting in the navy at the beginning of the war in Southeast Asia, and his two years in the service further scarred him. In many ways, by the time he was 22 or so, when most people are just hitting their stride, he was broken. He drank, used drugs, and generally didn’t have control of his life for the next twenty years.

When I say he didn’t control his life, I don’t mean to say completely. He was using and drinking and making a lot of mistakes, but he participated in some amazing things as well. When he got back from the war, he helped found an organization called Veterans for Peace. Along with a group called Vietnam Veterans Against the War, they helped provide a voice for veterans in the peace movement. People who knew what war really was were speaking up against war for the first time. He was beaten and arrested many times. It was a brave thing to do.

But by 1980, when I was conceived, he was at a low point. His first marriage had long since broken up. He’d struggled to hold a job. His PTSD and alcoholism were running his life. And he was entering his late thirties. He could see the path down which he was headed: at the end of this abuse would have been an early death.

From what I’ve heard, my mother told him he didn’t have to be involved in my life. She just wanted a baby, by whatever means necessary. She was prepared to raise me herself if that’s what it took. She’s told me since then that she had visions of me in the clouds — literally in the clouds. She’s not generally the type to have visions, but she was serious about this baby project. He could have just left.

So that’s where my dad was thirty-some years ago, when I came into the world. Moving from homelessness to a bad marriage. Alcoholic. Intermittenly employed and generally unemployable.

But like I said: this is a tribute to my dad.

Because the quality that I admire most in my father is his commitment to being better.

My dad got clean around the time he divorced from my mother, when I was a toddler. I still remember going to AA meetings with him. They had joint custody, but he couldn’t afford a babysitter. He liked to go to vets’ meetings, which in our neighborhood, the Mission in San Francisco, usually meant that half or so of the attendees didn’t have a place to live. While I colored in the corner, they’d talk about the low points of their lives, both at war and with drink. Even then, I think, I understood that my dad was learning to be better.

His PTSD was always part of my life. I’m not sure when I figured out that other kids’ dads didn’t jump out of their chairs when the ground rumbled from a grocery truck passing outside. Sometimes I would stand next to my dad as he was lost in the newspaper, and I’d yell at the top of my lungs in an unsuccesful effort to break into his private world. When something went wrong between us, he was like a prosecutor, his PTSD-paranoia in full flight, tearing me apart. It could be very, very scary.

But he was working so hard to be better. I remember once when I was thirteen or so, we were in a screaming match in the kitchen. When he was zeroed in on his target, he was unstoppable, undistractable, undivertable. With one hand, he pushed me back into the wall, six or eight inches. Honestly, it was quite a fight, but not much of a push.

A few hours later, he came into my room and apologized. A sincere, full-throated apology. He knew I hadn’t been hurt or anything, but he also knew that he was wrong, and wanted to make sure I knew that, too. It was something that in the moment, when we were screaming, would have been unthinkable. He was trying hard to be better.

When I was ten or twelve, he founded an organization called Jhai. The world, in Lao, means hearts and minds working together. He had met and befirended a Laotian woman who was a refugee from the part of Laos his aircraft carrier had bombed during the war. He started by bringing medical supplies to the village where her family lived, and over years helped the people he had so horribly wronged build community-owned schools and get access to communications infrastructre.

He called his process reconcialiation-based development. He was reconciling with these people who’d fled the bombs he loaded, but I think he was also reconciling within himself. It wasn’t a matter of doing penance. It was about being better today than he was yesterday.

My father told me that after his first visit to Laos, he slept through the night for the first time since he was a teenager. He didn’t sleep through the night every night thereafter, but he got better. These days, he tells me that walking is what helps him most. He does what he needs to do.

I wouldn’t wish PTSD upon anyone, nor addiction. And I wouldn’t wish a parent who suffered from them on any child. I can say, though, that I don’t wish for any father but the one I have.

Even when things were as horrible as they could be, when he was fighting my mother in court and fighting with me at home and struggling with his awful diseases visibly every day, I never doubted that my father loved me. I never doubted that he wanted me. I never doubted that he supported me becoming the man I wanted to be. And I never doubted that for my sake, he wanted to be better each day than he had been the day before.

I try to live my life by that example. Thank you, dad.