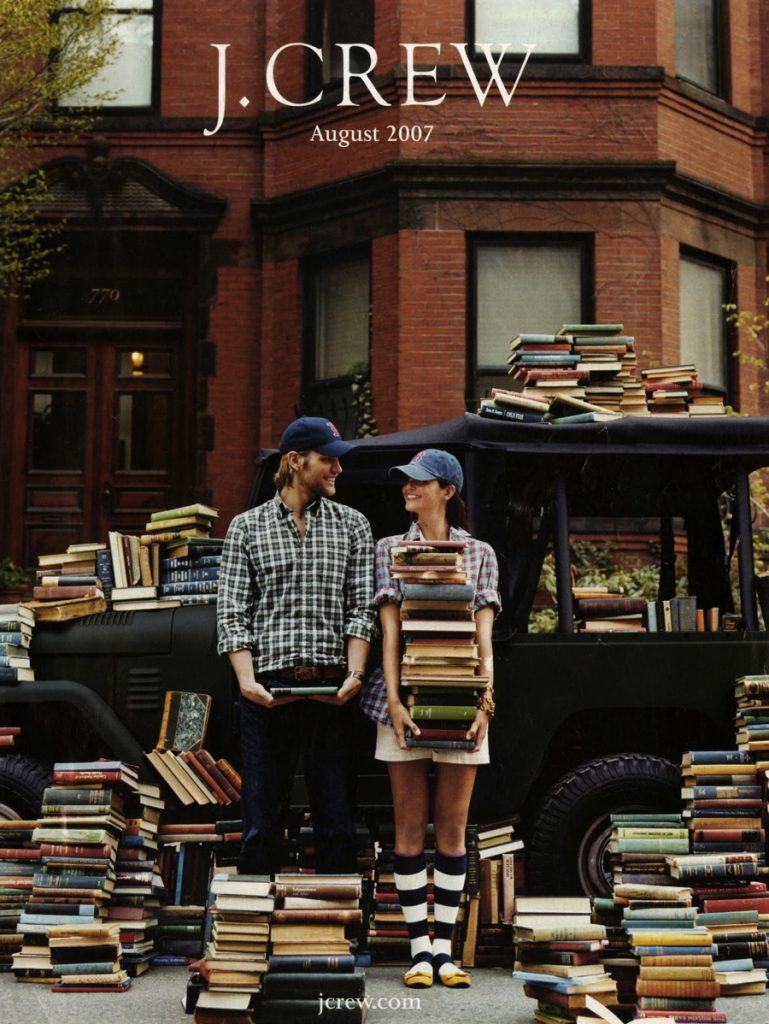

J. Crew filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on Monday morning, making them the first major retailer in the US to do so during the coronavirus pandemic. Vanessa Friedman of The New York Times was among the first to break the story. A day later, she wrote a post asking if consumers need J. Crew at all. Once upon a time, J. Crew was “the apotheosis of New England prepster style, crew-neck sweaters and wide-wale cords brought to you in a catalog of cheer.” Now it’s not clear what they stand for.

[T]he idea that brands deserve to be preserved, invented and reinvented ad infinitum is a late 20th-century creation. The notion is born from the luxury groups of Europe, who theorized that it is easier to restart an already established, if decrepit, name (hello, Patou!) than create one from scratch. It is not, however, an American tradition. Maybe it doesn’t need to be.

Traditionally, the United States has been happy to let brands live out in their natural life span — to believe they should not, necessarily, be seen as immortal — and be replaced by the new, the young, the of-their-time. Fashion history is rife with memories of bygone names: Bonnie Cashin, Claire McCardell, Willi Smith, Stephen Sprouse, Patrick Kelly. Donna Karan. Maybe J. Crew is ready to join them.

Today, consumers who shop for value have more options than ever. There are now thousands of digitally native brands that specialize in just one kind of item: UntuckIt has branded itself around short-hem shirts; Gustin has built a business around affordable raw denim jeans. And as J. Crew has faded, the middle of the market is getting squeezed by luxury brands and fast-fashion retailers. Mid-tier companies such as J. Crew and Banana Republic don’t have the uniqueness of the first or the price-competitiveness of the second.

If you want to dress in head-to-toe Gucci — or H&M — you still have stores for that. But for men who want something classic, generally appropriate, well-made at a reasonable price, you may soon have to scour the Internet for the best makers of socks, then chinos and then shirts. Then, you’ll have to figure out yourself how to combine these things into a coherent outfit, rather than rely on dedicated sales associates who know the story behind each piece — the sort of person who worked at, say, J. Crew.

When I submitted my article, one of my editors asked: “What happened to pleated pants? I used to wear them and then they just disappeared! But I never knew why.” This is why men still need J. Crew! The company is a bellwether for men’s style — they don’t set trends so much as they confirm them. For the millions of men who don’t want to have to follow every online discussion about pleats, J. Crew neatly curated everything for them in one place. Compare this with the other mode of shopping, where people have to read through thousands of internet threads and hunt down niche brands to effectively cobble together the same look.

This ended up getting cut from my article because I wasn’t able to flesh out the idea entirely, but I think the fashion industry also benefits from having “entry-level” stores such as J. Crew. It needs a way to bring new men into the fold. A small percentage of J. Crew’s customers will go on to buy higher-end clothing, including niche brands such as Crockett & Jones and Engineered Garments. This may sound ridiculous on first blush, but it’s the story of how the heritage menswear movement developed. If we raise the barriers of entry, however, either by requiring men to spend more time or money when building a better wardrobe, many won’t even take the first steps.