This spring marks the opening of a new men’s fashion exhibit at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the first of its kind at one of the world’s leading spaces for fashion research. Entitled “Fashioning Masculinities: The Art of Menswear,” the show is a trans-historical examination of masculinity in all its guises, arguing that men’s fashion is entering a period of increasing openness and expressiveness after two centuries of renunciation.

Broken into three main galleries — Undressed, Overdressed, and Redressed — the exhibit features over a hundred looks, ranging from bejeweled historical costumes to celebrated contemporary designers, such as Rick Ownes and Thom Browne. Though the show features many impressive outfits alongside a trove of artworks and objects from the V&A archive and borrowed from other institutions, it fails to draw a convincing through-line from gender-bending court frippery to Gen Z’s rejection of traditional masculinity.

Even a casual observer at this past month’s fashion shows (or the past decade, for that matter) would notice how much of men’s fashion has shifted away from rigid formulas in favor of increasingly expressive and “feminine” designs. What is valuable about shows like “Fashioning Masculinities” is how they can connect what may feel wholly of the moment to sometimes quite old ideas in fashion history. Like the Met’s recent and much more thematically coherent “Camp,” good fashion exhibits elucidate and elaborate on that history. Instead, “Fashioning Masculinities” offers an overbrief and distinctly Anglo-centric vision of men’s fashion that seems obsessed with tailoring while missing the significance of sport, work, or the military in defining men’s fashion and masculinity in the 21st century.

The show opens with an austere gallery devoted to underwear called ‘Undressed,’ which explores fashion’s relationship to the male body through undergarments that hide, shape, or expose the male physique. Using a palette of black, white, and nudes, the items on display focus on the creation of (and occasional challenge to) the Western male bodily ideal, going as far back as the hulking Farnese Hercules for inspiration. There are white linen shirts and white jockstraps, Calvin Klein ads, and a video of dancers performing Matthew Bourne’s Spitfire in their underwear. Classically inspired (and predominantly white) homoeroticism abounds. The alternative queer takes on the male body are more interesting, as in a black and white Ajamu X photograph of a lacy brassiere stretched over the muscular back of a black model. In the exhibit’s accompanying catalog, the complex tensions in men’s underthings – form and function, phallic symbolism and frank sex appeal – are expertly unpacked by Shaun Cole, Associate Professor in Fashion at Winchester School of Art. However, most of the historical and theoretical context is missing in the physical gallery, leaving too much to the viewer’s imagination.

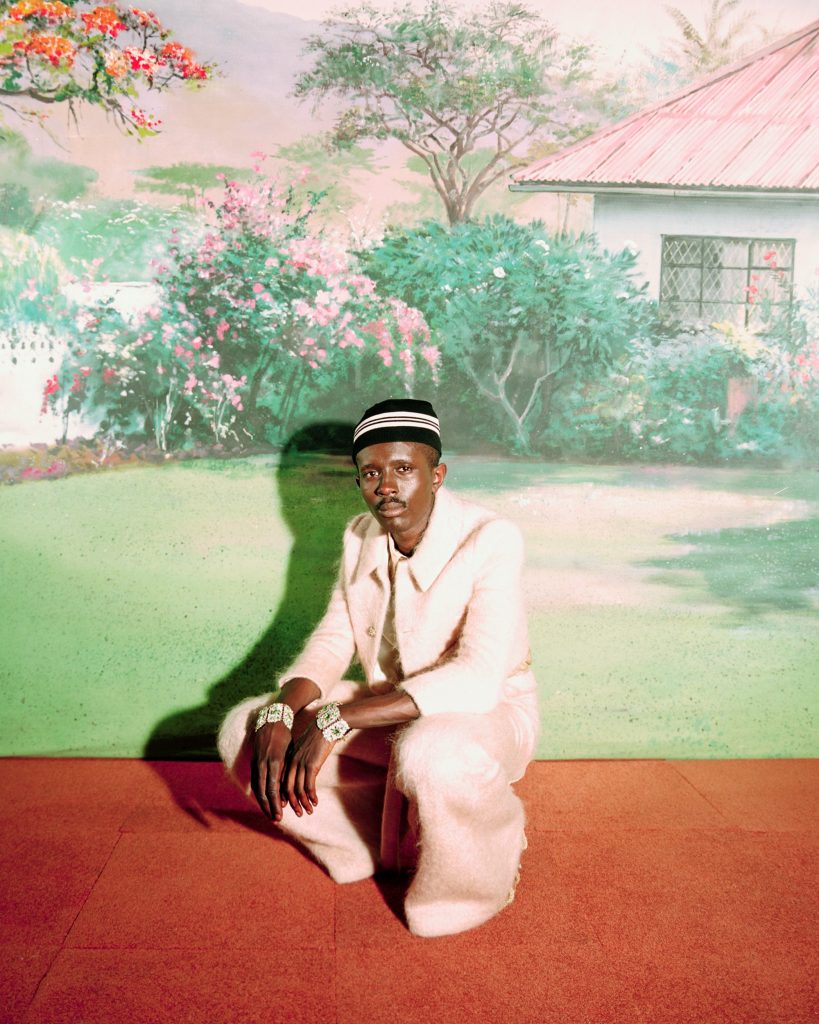

The following section, “Overdressed,” is a tour of the ways men’s fashion is connected to power and wealth–courtly swag, oversized silhouettes, lavish and colorful fabrics. Here, the show shines (literally), offering the viewer a cornucopia of outrageous fits. Personal favorites include a pink, fuzzy suit from Wales Bonner (pictured above); a garden party frock coat studded with roses, designed and worn by society and fashion photographer Cecil Beaton; and a hyperreal marble bust by Bernini of a young fellow with flowing locks and a lace collar so elaborate and expensive that even a devoted hypebeast would blush at the cost.

The organizing principle in “Overdressed” is color, resulting in a beautiful, albeit vapid rainbow of rich guy clothing. Gucci, a sponsor of the show, features prominently. Yet, beyond the idea that Englishmen have at various times dressed as lavishly as women and have sometimes borrowed from the sartorial traditions of China and India, the room does little to critically examine how that masculine display is connected to networks of power – cotton plantations in the Americas, deathtrap mills in Manchester, vast colonial holdings in the British Raj. As historian Sven Beckert persuasively argues in Empire of Cotton, for men of the mercantile and early industrial ages, fashion was not just a way to ostentatiously display their wealth. It was often the source of their wealth. This two-way relationship seems largely lost on the curators, with the result being more celebration than an examination of how guys have stunted through the ages.

The final gallery is meant to be a more critical look at what men’s fashion might be going forward, centered around the construction and dissolution of the suit. The problem with this room is that though it purports to be a corrective, it’s mostly a long and well-trod history of the garment most readers of this site are quite familiar with, the lounge suit. From a plaque on Beau Brummel to an elaborate display of mannequins and paintings dedicated to the fits of the Duke of Windsor, this is stuff most #menswear guys lapped up a decade ago.

However, there was one character I discovered in “Fashioning Masculinities,” who I think deserves to be canonized as a menswear icon: Maharaja Yeshwant Rao Holkar II of Indore. Immortalized in a life-sized 1929 oil painting by artist and fashion illustrator Barnard Boutet de Monvel, the Maharaja appears as the epitome of ultra-groomed, classic menswear elegance. He stands contrapposto, nonchalantly fingering his black satin lapel. Interestingly, Boutet made a second portrait of the Maharaja in traditional Indian dress (not on display), which shows the young royal in his official garb, staring blankly at the viewer as if he would rather be dressed for a party in London.

Ultimately, “Fashioning Masculinities” feels more like the start of a conversation than the final word. The contributions of “regular” guys are almost entirely absent. Arguably, football casuals, roadmen, and New Romantics have had more significant impacts on shaping the image of contemporary UK masculinity than Savile Row has. And it is this obsession with tailoring that causes the show to suffer from a strangely provincial idea of men’s fashion, mistaking upper-class English fashion history for a universal one. The final display, full of tuxedo ball gown mashups worn by the likes of Billy Porter and Harry Styles makes a powerful statement about where men’s fashion may be headed, at least on the red carpet. But as I exited my train at Cambridge Station (where black tie is still a regular part of life), I found that most guys were dressed in identical black puffer jackets showing off their college crests. It seems some men take a longer time to change.