When my teenage daughter was younger, my wife and I used to joke that she took her style from her nai-nai (her paternal grandmother, aka my mom). She wore bold colors in big prints and patterns. Her ensembles may not have always classically harmonized, but even amidst the visual dissonance, there was a charming playfulness, however intentional or not. Perhaps younger children and older adults embody a certain freedom of style, a sprezzatura flair, because they don’t conform to basic fashion norms (or never knew them to begin with).

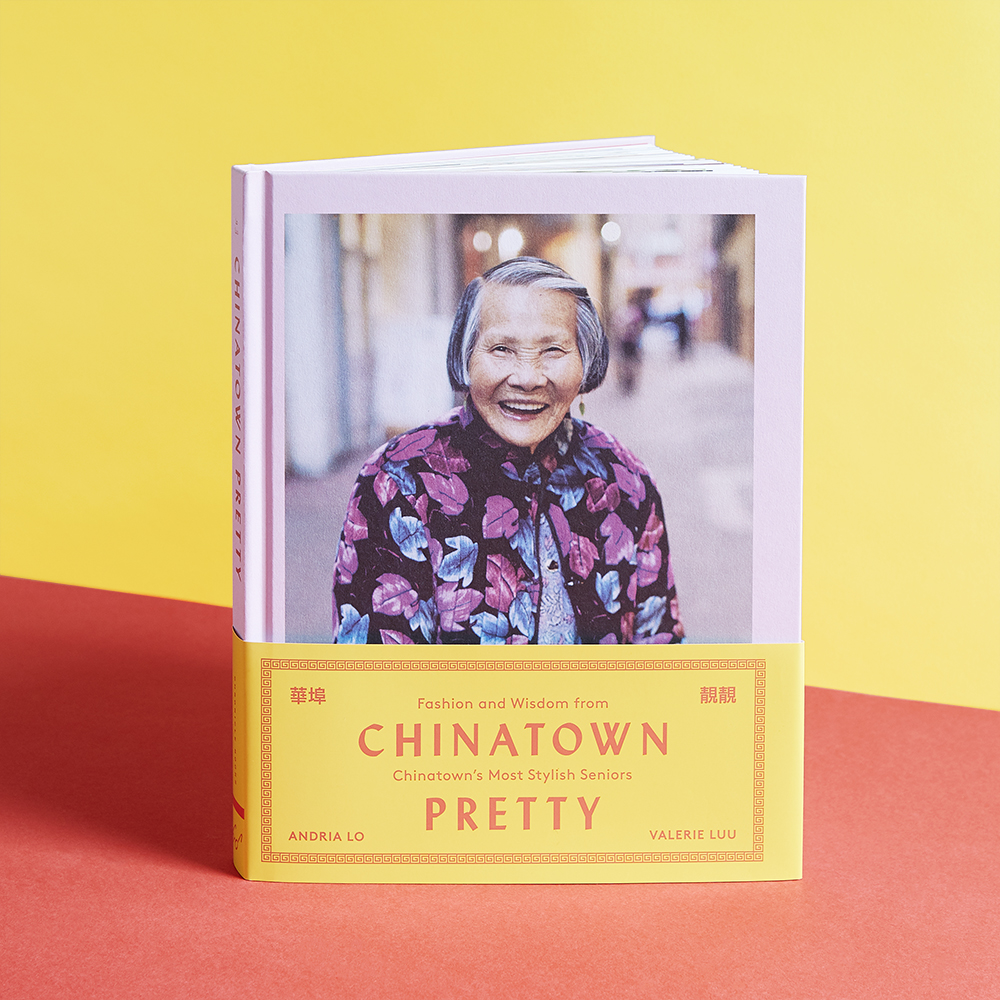

Amongst my fellow Chinese American friends, we all knew of aunties and uncles who rocked similarly outlandish outfits. It was a kind of inside joke, a sense memory similar to the menthol burn of Tiger Balm or the tart tang of Haw Flakes we grew up around. It didn’t occur to me that any of this was worth compiling until a few years back, when I stumbled across Andria Lo and Valerie Luu’s Chinatown Pretty, a blog and Instagram account, recently turned into a 224-page photo book.

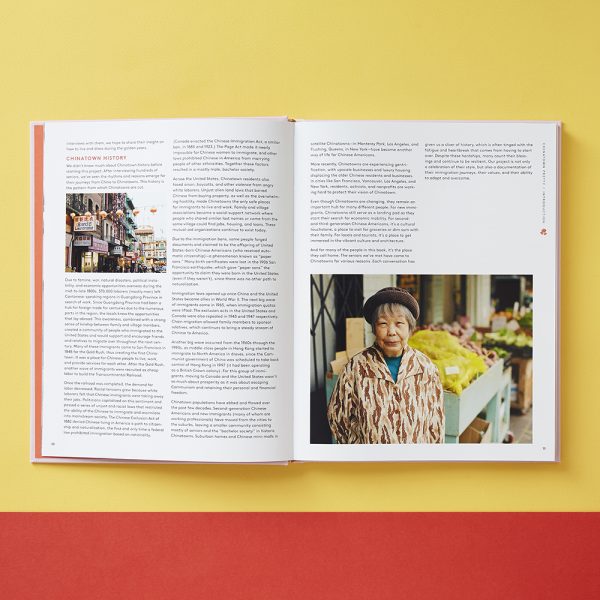

The idea behind the original blog and new book is that Lo and Luu went around various Chinatowns — including San Francisco, Los Angeles, Manhattan, and Vancouver — to photograph local Asian American residents and shoppers in all their resplendent glory. As they write in the book’s intro, “These Chinatown fashion icons share some of the same aesthetic sensibilities as hipster bloggers — except they’re eighty years old!”

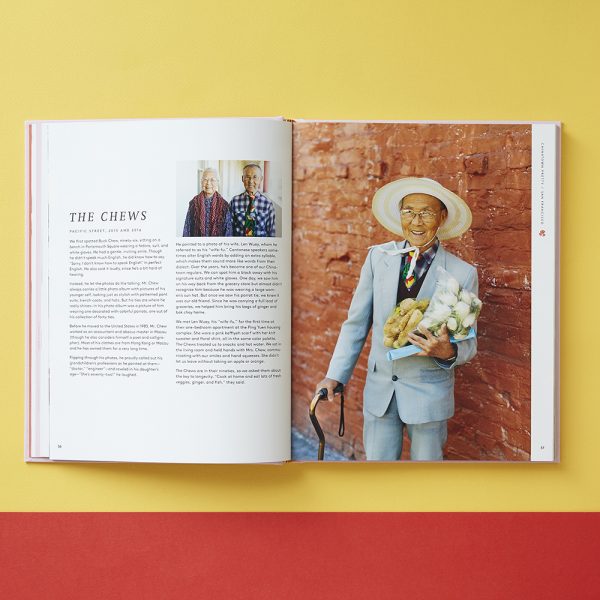

In total, Lo and Luu photographed and profiled over 100 women and men between six cities. In most cases, participants are primarily identified by some aspect of their outfit. For example, Merlot Man (Wai Ping Lam, 80) was seen in Oakland’s Chinatown wearing a deep merlot jacket with a matching beanie, plus flip-up eyeglass shades. Ten-Gallon Bucket Hat (Lau Wai Kwong Cho, 84) was photographed in Chicago’s Chinatown with her aforementioned bucket hat and a loose-fitting, Christmas-themed mock turtleneck that hid a homemade shirt patched with aqua gingham fabric and a wide strip of white, purple and black plaid.

One of my favorite subjects comes early in the book, spotted on San Francisco’s famous Grant Avenue: Two Hats (Huitang Peng, 75). He’s so named because Lo and Luu found him with a beanie beneath an oversized grey felt newsboy cap along with seven layers of tops. “I live in the Sunset, near the ocean,” Two Hats told them. “Sometimes when it’s really cold out there, I wear eleven layers,” (As someone who used to also live in the Sunset, I can relate).

If Chinatown Pretty was an inspo-board, there’s no shortage of smart style ideas to learn from. The Fox (James Yang, age unknown) showcases a classic monochromatic approach with his stone-colored pants, half-zip sweater, and 3/4-length jacket worn over a white dress shirt, with just a blood-red beanie adding a splash of contrast. At the other end is Silk Scarf (Mee Lee, 83), who participated in the Chicago Chinatown Senior Portrait Day. She’s cloaked in a riot of colors, from a deep teal winter parka worn over a fire engine red zip-up fleece to the titular silk scarf, originally from Shanghai, adorned in pink flowers and lapis-blue leaves, the latter of which accents the blue-green of her coat.

It’s tempting to classify these as “accidental street style,” but that’s not giving the wearers enough credit for putting thought into their daily fashion. An 80-year-old shot outside a Chinatown produce market isn’t inherently less conscious about their personal style than a 40-something shot in Florence during Pitti Uomo. As Lo and Luu note, there’s an inherent “urban utilitarianism” to their subjects’ choices, conditioned by immigrant pragmatism and especially for seniors, the realities of living on a fixed income. The two authors write, “These outfits weave together the seniors’ diaspora: where they came from, what they did for a living, how they made the best of their circumstances.” The origins of streetwear in ‘70s hip-hop culture share this same ethos: inventive adaptation arises from conditions of scarcity.

Chinatown Pretty is also notable for being one of the first, if not the first, mass-market book dedicated to Asian American fashion. There have been, of course, books chronicling individual Asian American designers such as Vera Wang, Anna Sui, and Vivienne Tam. There are also entire bookstore sections on fashion in Asia, but chronicling Asian American street style hasn’t exactly been on most publishers’ radars. In Thessaly La Force’s April article in T Magazine on Asian Americans in the fashion industry, the author notes that “Asian-American representation in the broader glamour industry…has been slow to come… Whatever lingering resistance exists to seeing Asian-Americans speaks to a persistent invisibility.”

However, it’s telling that Chinatown Pretty’s intervention — welcome as it may be — relies on a well-established, but troubled, exception to this “persistent invisibility”: Chinatowns. The book includes a short history of the Chinese community in America, including specific backstories for each of the six Chinatowns that Lo and Luu visited. Still, the two mostly steer away from discussing the historical legacy of these neighborhoods as exotified tourist destinations.

This is especially true for the Chinatowns in San Francisco and Los Angeles, both of which are “new” since their original versions were either demolished by an earthquake and a fire in 1906 (San Francisco) or displaced by the construction of Union Station in the 1930s (Los Angeles). In both cases, virulent anti-Chinese lobbies wanted to use the destruction of the traditional Chinatowns as a way to permanently disperse the Chinese American population away from the city centers. However, local organizers convinced civic leaders that new Chinatowns could help generate municipal revenue by appealing to tourists, and thus, were allowed to rebuild near their respective downtowns.

This is why the colorful architecture in most Chinatowns doesn’t resemble anything you’d actually find in China: they’re deliberate, Orientalist fantasies. As the design podcast 99% Invisible argued in their episode about Chinatown architecture, “This was exactly the Westerner-friendly version of China [tourists] wanted: vaguely exotic, but safe enough for middle-class White America. The visitors began to flow into Chinatown, and so did their cash. The result was a success financially, but it also perpetuated stereotypes about Chinese culture.”

Chinatown Pretty’s core conceit partly rests on this cultural legibility of Chinatowns for non-Asians. After all, the places where most Chinese American seniors actually live are not central city Chinatowns. They’re suburbs, located in places like Los Angeles’s sprawling San Gabriel Valley or Richmond, just south of Vancouver. From a pure streetwear perspective, you can find similar outfits amongst Asian American residents in Rowland Heights, CA, Flushing, NY, and Naperville, IL, but Chinese American Suburban Enclave Pretty doesn’t have the same ring to it.

And yet, Chinatown Pretty also undoubtedly helps to challenge stereotypical impressions of Chinatowns through the stories (and styles) of the people who depend on them as their home and social center. If one ever needed evidence of the heterogeneity of the Asian American community, you can find it in the book’s expansive diversity of personal fashion, from the matching yellow sweatsuits worn by The Jungs (86) of Los Angeles to the plum purple knit vest and blue and orange Mets cap of New York’s The Gardener (Gui Zhi Li, 73) to the spectacular Botan Rice apron dress draped onto San Francisco’s Polka Dot (Dorothy Quock, 83). Though the book advances the idea of “Chinatown pretty” as an aesthetic, it’s also quick to highlight that no two people wear it quite the same way.

I don’t mean to end on a dark note, but it’s hard to ignore one reality haunting the book’s pages: not only are these 70- and 80-year-olds in the twilight of their years, but so are the Chinatowns themselves. Most are being transformed by the forces of gentrification in which the land value of blocks located near city centers and transit hubs outweigh the needs of locals who need affordable places to live and shop. As a compendium, Chinatown Pretty is also a snapshot of various communities in danger of disappearing within a generation.

This point certainly isn’t lost on the people in the book itself. Dora the Explorer (Xing Jun Ma, 86) was spotted at the Sun Wah Centre in Vancouver. Besides being an active tai chi practitioner, she’s also involved in the Chinatown Concern Group, which is challenging development plans in the neighborhood. With her matching magenta sneakers and backpack and periwinkle-blue skirt suit, Ma seems poised for taking action at a moment’s notice, and as she told Lo and Luu, “our Chinatown doesn’t look the same as before, so I want to help.”

(Images via Chinatown Pretty: Fashion and Wisdom from Chinatown’s Most Stylish Seniors, by Andria Lo and Valerie Luu, published by Chronicle Books 2020)