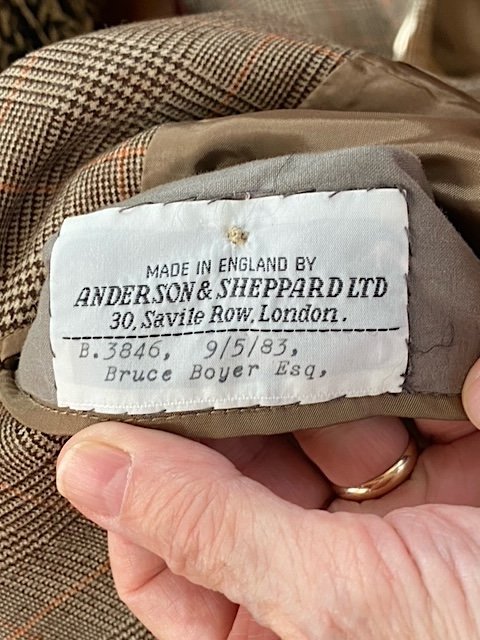

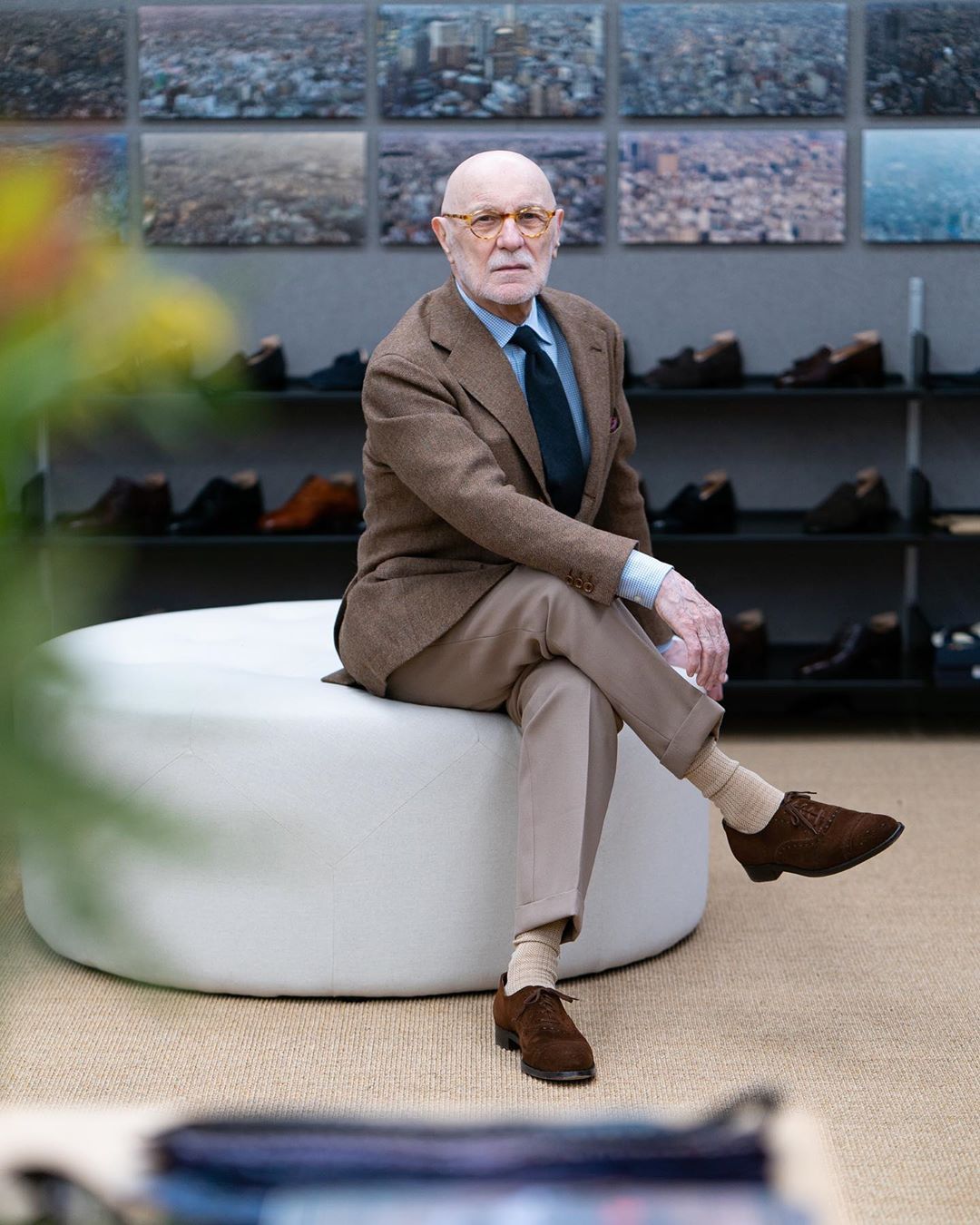

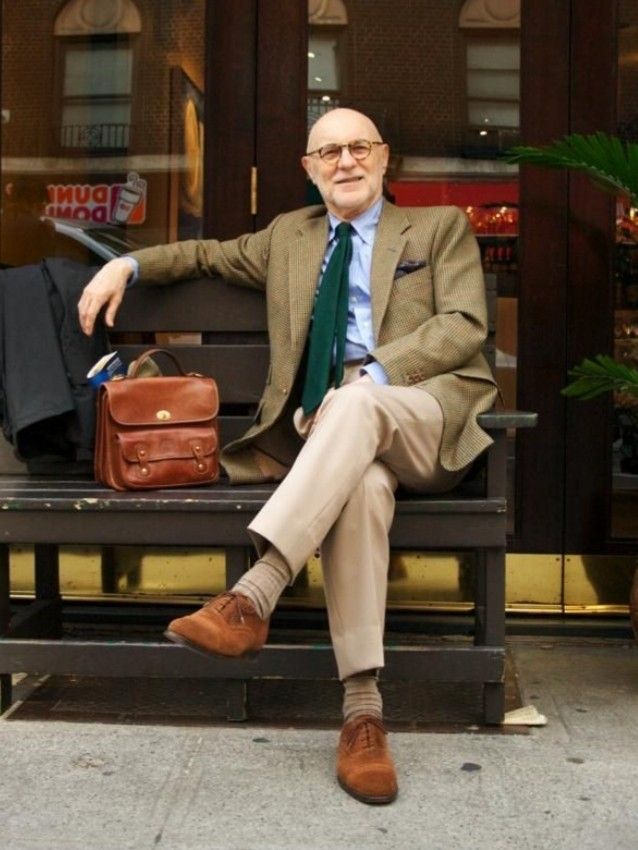

In a post last month at Permanent Style, Bruce Boyer shared some charmingly low-res images of his Anderson & Sheppard sport coat. It’s made from a clear finished, 14oz worsted wool, a brown version of the classic Prince of Wales check. Cut with a soft shoulder and draped chest, it looks wonderful on Bruce, as he pairs with tan cavalry twill trousers, a light blue shirt, and a blue striped tie. Tucked inside the right in-breast pocket is also a small hand-sewn label that neatly reads: “Made in England by Anderson & Sheppard Ltd, 30 Savile Row, London. 9/5/83. Bruce Boyer Esq.”

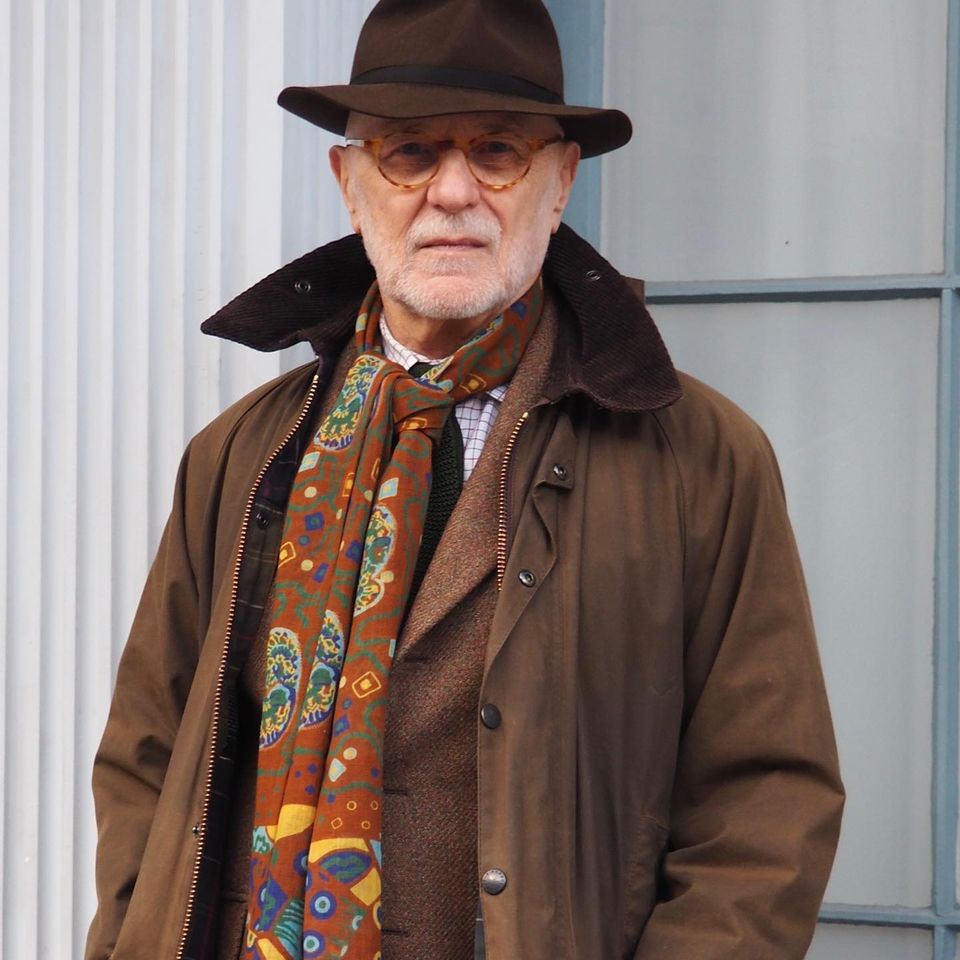

The word classic is the most overused descriptor in fashion writing. Yet, 37 years after Bruce walked into Anderson & Sheppard to commission this coat, he still looks great in it today. Much of that is thanks to the moderate proportions — the lapel, length, and shoulder line don’t veer into the extreme — and consistency of Bruce’s good taste. If you scroll through photos of him online, you’ll always see him in the same British-Ivy clothes. He looks the same today as he did when we featured him in our webseries nearly ten years ago, or when he first appeared at The Sartorialist in 2007. Open the back cover of his 1985 book Elegance, and there you’ll see Bruce’s author photo. He looked younger back then, but was still dressed in the same unmistakable clothes.

While reading that Permanent Style post, I thought about how wonderful it would be to consistently wear something for 37 years. Clothes described as classic are not often timeless — many can be easily pegged to an era or age, as evidenced by what you find in thrift shops. “Classic menswear” ten years ago — as it was worn with trim pants, colorful bracelets, cutaway collar, and double monks — also looks terribly dated today. Yet, Bruce’s style is proof that some things do age well. Such a proven track record is refreshing at a time when new clothes, silhouettes, and style archetypes debut by the minute, and many are concerned about the fashion industry’s contribution to a global climate crisis. So I reached out to Bruce to talk about how he built his wardrobe, what advice he has for a younger person, and how classic menswear might fit into broader discussions about sustainability.

Derek Guy: I’ve always admired the stability of your style. But before you wore the clothes you do now, did you experiment much with clothing? Are there things in the Bruce Boyer archive that you regret?

Bruce Boyer: You use the word stability to describe my style so delicately and diplomatically. The fact is, for better and worse, I’ve worn the same style of clothes since I was 15 or so. It may seem strange, it sometimes does to me, that I would have been so taken with my appearance at an early age. I can only explain it by thinking that I was a rather short and scrawny kid in a blue-collar neighborhood, and looking for survival tools, I hit upon style as a weapon. I was merely adequate at team sports, not particularly handsome, had no father as a role model or teacher. I believe I had a highly developed sense of humor and good manners — and those two attributes will get you halfway there. But how to go the second half? I must have started to closely watch the older guys and how the more successful ones did it. The “wheels,” as they were called, had specific ways of walking and talking, certain poses, special language, and particular forms of dressing. I looked and learned.

So fortunate for me, I had a mother who allowed a certain freedom in choosing my own clothes even from the time I was perhaps six or seven. Her rule was that when I was with my friends, I could dress any way I wanted. But when I was with family, I would dress more appropriately. It was a good deal, and so I was allowed to experiment with my “looks.” When I started my teenage years, it was both the twilight of the zoot suit era and the age of The Rebel Look years of the 1950s. I wore a zoot suit for a very short time (a big mistake for a skinny, short kid) and a black leather biker jacket and engineer boots a little longer. I lost interest in the zoot look quickly, but still to this day admire the biker look. Most of the clothing I see today has its roots in the ’50s — the Rebel look, the Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, Italian styling, the British approach, ranch wear, and prole gear — and we absorbed it through movies and adapted it for ourselves. I wore it all, kept wearing those items that worked for me (jeans, flannel shirts, ranch jackets), and forgot things that didn’t (black leather motorcycle jacket, pegged pants, “stingy brim” hats, engineer boots, Chelsea boots).

When I entered high school, I was put in with kids from other parts of town and introduced to the Ivy League Look from the city’s wealthier section. I immediately took up this look. I pestered my grandparents, the sweetest people on earth, to buy me a Harris tweed sports jacket I’d seen in our local department store, and that was the start of my lifelong style of dress. I became a fan of Fred Astaire, Marcello Mastroianni, and Sean Connery, and while I didn’t look like any of them in any way, I found I could adapt things they wore to suit me. So, in addition to my Ivy wardrobe, I added a few “Continental” items (a dark grey, mohair double-breasted suit and a brown puppytooth, single-breasted one), Cary Grant collared shirts (they were about a half-inch higher than normal and were called “High Boy” collars), flannel trousers, and other items. For my graduation present, I opted for a gray flannel made-to-measure suit, the start of my road to clothing depravity in the custom clothing trades.

So my wardrobe was mostly khakis, button-down oxfords, and Shetland sweaters when I entered a small Ivy League college, mixed with a few more international items from Italy and England, and the Army & Navy store. In my four undergrad years, I perfected what has become my personal look. We had an excellent campus shop and several good trad shops. Then I discovered Langrock in Princeton, a repository of great American and British clothes in the days when Princeton students and their profs were still dressing like they meant it. By that time, I’d also started regularly going to Manhattan — plays, concerts, nightclubs, museums, girls, clothing stores, record shops — and discovered all the important stores there: Brooks Brothers, J. Press, Chipp, Saks Fifth Avenue (wonderful in the 1950s), and others which are no longer sadly there.

Additionally, I went to Europe for the first time in 1963 and discovered both Savile Row and Carnaby Street. I liked Savile Row better, and never really got into the floral shirts with long collars and such. I hunted out the classic shops. People ask me how I could afford those clothes, but they have no idea how inexpensive things were in England at that time, just a few years after the war. You could get a very good off-the-peg suit at any number of stores in the heartiest cloths for under $100. On my second trip to London a few years later, I bought a bespoke three-piece flannel suit from Bailey & Weatherill for $125. I was able to visit London every year in the ’60s and ’70s, and I’d pack light and simply buy what I needed to wear there. Somewhere in the ’80s, things started to change dramatically, and clothing prices rose along with everything else.

I began my short teaching career in 1964. A few years later, it was evident that we were entering a new era. There were outward signs. The Beatles arrived in ’64 with their Carnaby Street style and created an uproar for all things British. I’d been to the “Mr. Fish” store in London and tried a few flamboyant shirts and wide ties, but by this time, I was already stuck in my Ivy-British conservative style. Then came the deluge for Ivy style. It was the Summer of Love in 1967 and Woodstock in 1969; students returned to their campuses after burning all their Ivy gear. They adopted the uniform of tie-dyed t-shirts, distressed bell-bottomed jeans, Afros, and kurtas (Indian collarless shirts made of dyed cotton). I continued to wear a suit or sports jacket and tie when teaching on campus, even though I sympathized with the student movements that were occurring. So, in summation, I’d say that my years from 5 to 14 were experimental. The years from 14 to 20 were hardening and trying to perfect my image (still working on that, but with less concern). I occasionally try a small experimental gap into a slightly wilder tie, bolder striped shirt, or colorful sweater. I recently discovered the color purple and wonder why I’ve never had anything purple before. But my wife continues to say that all of my tweed jackets look the same (and she’s right). I recently thought to buy a new overcoat and finally got one: a Gloverall duffle, exactly the one I wore as a freshman in college. All my friends know I’m hopeless.

So the “perfecting” part of it continues as life changes, without as much enthusiasm, but with as much interest. I’m not interested in looking younger than I am; I’d rather try to look the best I can for my years. I haven’t needed clothes for decades because I maintain what I buy, but I still occasionally get a flutter when I pass by a display of nice sweaters, and one of them whispers, “take me home with you.”

DG: What advice would you give to a younger person who’s trying to build a more sustainable wardrobe?

BB: The idea of sustainability has, of course, been in the air and on the pages now for some time, but I like to think I’ve always promoted sustainability because I’ve always advised young men to buy the best they can afford and take care of their purchases. That is, wash and dry clean properly, have clothes professionally altered and repaired, and store garments and accessories appropriately. I’ve always said that two good pairs of shoes are preferable to six cheap pairs. People should get away from considering merely the purchase outlay, and instead consider the lifetime of the garment. These ideas should lead young men towards quality and classically styled clothes. I’ve never promoted fashion and never will because I think it’s wasteful to buy new clothes every season or two. My touchstones are quality and style. And I’ve found that I like my clothes all the better as they age. I’ve always thought that style isn’t fashion, and fashion isn’t style. And I’m happier with style.

A while ago, I was told by a friend that someone had, gently I hope, criticized me for dressing like an old person. I didn’t know whether to be flattered, shocked, puzzled, or angry. I decided on puzzled because I AM an older person and can’t think how I should dress if not like an older person. I simply want to be a well-dressed version of my age and believe that mutton dressed for lamb is a bit silly. Not that people shouldn’t dress any way they want, I just feel most comfortable dressing my age.

Finally, I should say a young man should experiment, try different approaches. It’s a way not only of finding what sort of clothes work best for you, but I believe it helps you find yourself in more profound ways as well. The herd’s pulling influence is strong, but you’ll be happier finding and being yourself in the long run.

DG: In GQ last year, Rachel Tashjian wrote, “The Most Sustainable Idea in Fashion is Personal Style.” Her article is basically about how it’s OK to enjoy fashion, but to turn yourself over to it entirely is to forgo individuality. And when you do that, you’re continually chasing trends. True sustainability comes from having the confidence to wear things you like even when they’re suddenly no longer considered cool.

I like her message and find it to be true when I look at the broader fashion world. Some guys have worn Rick Owens forever — longer than some who got into tailored clothing ten years ago and gave it up after five years. Bill Cunningham made the French chore coat and tan khakis his uniform. But to get to that position, guys have to consume a considerable number of things — buying and discarding, buying and discarding. How do you suggest someone find their personal style quicker and more efficiently?

BB: You’re referring to clothes and developing a wardrobe, but the question’s so difficult because I think it’s true that “style is the man.” Then the question becomes: can a person develop his style quickly, efficiently, less painfully? The diplomatic answer is yes, partially. If a young man does some homework — reads the few books that aren’t just bullshit, looks closely at how the guys he admires do it, pays some attention to admirable blogs, and asks pertinent questions when he shops — he may be able to shorten the time and save a bit of money. But in reality, we’re talking about a person developing himself, his outlook, his philosophy of life, his aesthetic, his lifestyle (for lack of a better word). There are all sorts of “lifestyle” programs, “lifestyle coaches,” and other courses promising to shorten that process. I have my doubts, particularly when swift improvement, awareness, or goal achievement is promised. It seems every season, some new guru promises salvation, but invariably he’s as quickly forgotten. So I’m dubious that there are any shortcuts to developing style. Many have looked for this golden fleece for so long and tried so hard. I think we must assume that style isn’t won easily. Those who have it are held together with scar tissue.

DG: It feels like a lot of what you write says the same thing as Tashjian’s article. You have to have a sense of personal style and not be as moved by trends. You often recommend that guys anchor themselves in more classic clothing. Yet, a lot of classic clothing has proven to be its own trend. Many guys who wore suits and sport coats ten years ago have moved on because they feel it doesn’t suit their lifestyle. Aldens have been swapped for Nikes; sport coats for Patagonia fleece. Do you think investing in a classic wardrobe still has meaning, given what’s happened in the last ten years?

BB: That classic clothes may be a trend now and again is, I think, perfectly valid. It’s usually believed that these things go in cycles and that “dressing up” alternates with “dressing down.” There’s a psychological theory that we grow tired of one thing and must move on to another, and that this movement is like a pendulum. Some argue this is usually a 5-year cycle; others say 10-year and even 20-year cycles. I find most of these theories too simplistic to be entirely believed. But here I’m sailing into the shallows of my mind; I’m not a cultural critic or sociologist or psychologist. I do note that trends these days do move with a rapidity unknown to past ages, but I’m no longer attuned to them as I once was.

As for advice, I think people should dress as they want, within the confines of the law of course, and that it’s probably best to wear the clothes that best suit a person’s lifestyle and profession. As we all know, clothes send the most blatant kind of symbols about who we are in society, and it’s probably a good thing to send clear, truthful signals unless we wish to deceive others. There is a glaring exception to this advice. A person may have an interest in clothes and enjoy dress for its own sake, as a hobby, or some other personal reason, just as a person who rarely writes letters collects stamps. After all, most of us don’t need half of the clothes we buy, but we find joy in them. And what’s the harm in that?

Finally, I do think that some otherwise sane citizens worry too much about clothes. I’m not thinking of your blog site, Derek, but years ago, when I first started to see these clothes sites popping up, I was surprised to discover how many men were becoming interested in dressing as a blood sport. This then becomes a game of one-upmanship. Nothing wrong with it, and it serves to keep them occupied; who knows what trouble they’d get into otherwise. The line between interest and madness with some of these men is rather too thin, and I find it sad that some don’t get the joy out of clothes that they might. You can always tell the guys who are genuinely interested because they have a veneration for their old clothes. The punters don’t even have old clothes.

DG: Your point about having a veneration for old clothes seems like the heart of this issue. Sustainability, to me, feels more like an emotional thing. Sometimes I see designers talking about sustainability — the sustainability of the materials, the production, or even the design. But it feels more like a consumer issue. Ultimately, the lack of sustainability comes from us loving novelty. We want new clothes, new designs, and new style archetypes. Fashion is a culture of nonstop neophilia. In the last few years, I’ve been trying to emphasize the emotional aspect of clothes, so hopefully, people find joy in their clothing. Ideally, that joy stays with them and they don’t feel the need to replace what they own. But how do you find clothes that will eventually resonate with you long after you’ve purchased them?

BB: I often tell people that the best diet is to buy expensive clothes. I’ve maintained my weight consistently over the years because I can’t afford to keep buying new clothes. Well, I could if I bought cheap clothes, but I feel better in good clothes — i.e., clothes that fit, have lines that make me appear more attractive, and have the styling I prefer — and good garments usually have a high initial cost. I was taught to take care of my clothes, and so the initial cost is only one of the factors I consider. For me, the long run can sometimes be several decades, so the cost isn’t too exorbitant. If I remember correctly, Simon Crompton at Permanent Style once did a breakdown of prices, which showed that the garment with a high price tag can often be the most economical over the long run. I believe the term economists use for this approach is “prorated.”

For me, this approach applies to all my clothes, from jeans to socks to suits. But I’d say it’s particularly important with the more costly items in the wardrobe, such as overcoats, sports jackets, and suits. I don’t mind a flutter on a slightly garish tie or pair of socks once in a while, and if I quickly grow tired of them, there’s not much lost. But putting out a few thousand dollars has a way of concentrating my mind wonderfully. I want to make sure I’ll still like the garment years from now, that it can stand wear, alteration, and cleaning over the years. That’s why my suits are almost always conservative in cut and color, and why I choose them with an eye for accenting them with virtually any accessory in my wardrobe. My wife says all my suits and sports jackets look the same, and she’s right: all my suits are either some shade of grey or brown, and my jackets are reliably a shade of either green or brown. I might add that this is not a matter of what I think “suits” my appearance. I don’t worry about that because most of those “rules” are rather simplistic and stupid. I wear the colors and patterns I like, the ones that make me happy, and whether they make me more desirable in others’ eyes is not my concern. I know what I like, and that’s what I wear. Occasionally something new will come along for me to try, but these peccadilloes are more often failures than not, and I’m only glad I didn’t spend more on them.

I think, in short, that a man should experiment when he’s young, discover what suits him and what he likes and what fits into his lifestyle as he goes out into the world, and refine that approach as his life moves forward. But I’m aware that this pattern no longer makes much sense in a world of rapid change. Still, I think it makes sense for a person to work a bit at knowing himself. That may be the only constant available to us.

DG: What are some of the oldest things in your closet that you still wear? How did you come across them, and what makes them special to you?

BB: This would be a far easier question for me to answer if I were asked to mention the new items in my wardrobe. Writing about the older items would take a book (and now I’ve given myself an idea). But I can mention a few prototypical things to give you an idea. On my second trip to London in 1965, I discovered the shoe-making firm of G.J. Cleverley, then on Jermyn Street, I believe, and managed by George Glasgow Sr. and John Carnera. I bought an off-the-shelf pair of tobacco brown oxfords with, as Mr. Glasgow told me winkingly, a “suspiciously” square cap toe and ram’s horn punched detailing. I’ve bought many other shoes from him over the years and have them all, including this suede pair that will celebrate its 56th birthday this May. I’ve had them re-soled and -heeled half-a-dozen times or more. My wife says they’re ready for the Smithsonian, but I reckon I can get a few more years out of them with the good help and expert hands at Cleverley.

I’ve got three dress overcoats, the oldest of which was made for me by Garrick Anderson in 1984. It’s an English covert cloth coat in the traditional olive color, but I had it made double-breasted, rather than the traditional single-breasted, just to be a bit different. It’s worn like a warhorse, although I’ve done a bit of stitching around the collar and gorge myself to reinforce a worn seam. I’ve also stitched up a hole in one of the side pockets and re-attached a few buttons. I’m a dab hand with buttons; once I sew them on, they never come off again. And, oh yes, a few years ago, I had the coat shortened a bit to just below the knee.

I’ve got hundreds of ties. People give me them, and I often pass them along because picking ties for me seems almost impossible. I wouldn’t trust my wife to pick a tie for me, nor most friends. Ties are such an individual thing, probably because they’re totally useless and function almost exclusively as a symbol of status and occasionally of personal aesthetics. The oldest tie in my collection is one given to me by an old friend now deceased. He was a graduate of The London School of Economics and Political Science. We met up on one of my visits to London — this one, I believe, was in 1969 — and I noticed and commented on the handsome repp silk tie in purple with light blue stripes he was wearing. He mentioned it was his university tie. No more was said, but on my return home, a package was waiting for me containing a London School tie. I’ve still got it, it hangs there with the others, but I seldom wear it now. I suppose the happy memories now make me sad.

I mention these three items because they illustrate the way I acquired my wardrobe. It came to me bit by bit, in the course of events. Many of my clothes are encased in memories, and to part with them would be difficult. And since the quality of these items is high, I don’t see why I shouldn’t keep and maintain them. I understand that, while some have a more timeless style than others, these items are old-fashioned. But how else should I dress? To me, the height of idiocy is for a father to try to dress like his son. It shows the father doesn’t know himself, and his son won’t respect him for it.

DG: Men who wear tailored clothing well and have a stable style often have custom tailors. It’s not just that they have jackets that technically fit them well, but they have clothes made in more moderate proportions, unmoved by ready-to-wear trends. For you, your lapels are never too wide or thin. Your trousers have a classic silhouette; the jacket terminates halfway between your collar and the floor. The shoulders, similarly, are never too soft or structured. In this style versus fashion rubric, it allows you to look stylish even if your silhouette isn’t “of the moment.”

You mentioned earlier that you started buying custom clothes when things were more affordable. But nowadays, the prices have skyrocketed. Bespoke sport coats commonly start at $3,000; suits are $5,000 and up. There are more classic suits and sport coats off-the-rack, but they’re typically not your $500 items. They are still in the many thousands of dollars. If someone wants to build a stable wardrobe without having to reinvent their silhouette every ten years, is that possible on a reasonable budget?

BB: The tailored suit and the accessories that support it have been around in recognizable form since the middle of the 19th century, let’s say roughly 175 years now, which is a pretty long run for a costume. But for the last 75 of those years, fashion has sped up considerably, and certainly, the movements towards comfort and democratic casualness in our clothes have been the driving force. Now we are also involved in the forces of sustainability and globalization. Where this will lead us regarding our wardrobes, I have little idea, but I do see it has produced an unparalleled variety of choices, which in turn has produced considerable social anxiety. It used to be that clothes were a blatant symbol of one’s place in society, which worked very well when class systems were hardened. But when the social stratum becomes porous, when people’s destinies are no longer written in iron, how is one to dress? In the past forty years — at precisely the same time as the rise of the menswear designer — there has been a plethora of books providing advice on how to navigate the turbulent waters of the social wardrobe. Most of these books are entirely outdated because (1) they weren’t written very well to begin with, and (2) they concentrated on “rules” of dress, which became irrelevant almost before the books were off the press.

That’s the background. So what of the present and near future? With the price of the bespoke crafts today, it’s become clearer and clearer to me that no one needs customized clothing. I suppose there will always be those who need to show their position in society in various outward symbols, including their dress. And there will continue to be people for whom clothing is more of a personal interest than a necessity. I would put myself in that latter category. But for most people, decent ready-to-wear clothes are now available in such a profusion of styles, quality, and the price I can’t imagine it necessary to spend one’s whole salary on outfits. In fact, technology has made good quality, personalized clothing more available than ever. A variety of made-to-measure commercial operations — which first came to the fore of fashion for men in the 1970s — can produce tailored garments acceptable to all but (1) the extremely difficult to fit, or (2) those whose tastes are either so refined or so bizarre as to need true custom work. Additionally, the so-called casual revolution in dress has provided the freedom of choice, although I see few taking courageous advantage.

DG: Classic, tailored clothing, as a style, often seems more sustainable to me than casualwear because it’s the lingua franca of men’s clothing. It’s something that everyone can quickly get into without consuming a mountain of things to pick out a small handful of pieces that represent them. It’s flattering across a wider range of body types. It doesn’t force you to ask as many existential questions. Yet, classic tailored clothing feels like it’s devolving into a costume. To wear it on a semi-daily basis, at least outside of specific industries, you almost have to mark yourself as a clothing enthusiast. Do you feel that it’s harder to build a sustainable, stable wardrobe in casualwear? Is this very wide, open world inherently unsustainable in terms of clothing consumption?

BB: I think you’re right in sensing that tailored clothing seems to be devolving more and more into costume. The gentlemen most interested in tailored clothing have created a world where the past is not merely a reference, but a refuge. I say this not as a judgment, but rather as an observation that these men take nostalgia seriously. Fashion is always a language of references, and these men seem to live in a gated community of aesthetic sentimentality. I see nothing wrong with this, and there are certainly worse vices. I suppose what I find hypocritical, but at the same time hilarious, is that some profess an interest in craftsmanship when they are, in fact, merely using clothing as a weapon in a blood sport. No one we know, of course.

I wonder if the categories — formal, business, casual — are themselves outmoded in thinking about clothing today. And thus, the very idea of “building a sustainable wardrobe,” casual or otherwise, may in itself be irrelevant and obsolete. It does strike me, if I can use this spot to mention another point, that sustainability historically has been the norm, and it’s just been in the modern age, an age of corporate commercial consumerism, in which we’ve turned our backs on the idea that the world is finite. We should care about what sort of a place we leave our children. I believe we must quickly return to the concept of “stewardship” of nature, or perhaps “partnership” would be a better description. Failing that, I can’t see that anything else matters.

DG: Let’s address the 800-pound gorilla in the room. Discussions about sustainability always fall back on the same prescriptions: buy less, buy better; don’t buy anything at all; or buy vintage where you can. Especially for casualwear, the world is awash in good vintage clothing. But ultimately, whatever path you choose, sustainability means not buying as many things.

Yet, in this COVID-age, so many of the businesses we know and love are on the brink of bankruptcy. Good stores and factories are shuttering; craftspeople are leaving their trade. For many people, both here and abroad, the fashion industry isn’t just about frivolous consumption, but how they earn a living to pay for food, housing, and medicine. Is capitalism unsustainable? How do we reconcile this concern for environmental sustainability with the sustainability of jobs and the industry we love?

BB: Capitalism is unsustainable if coupled with CCC [Corporate Commercial Consumerism]. I’m not a professional economist, sociologist, or politician, but I don’t think it takes any of these to see that the scientific evidence is in. We can read the writing on the wall clearly: pay attention to the environment or be doomed. If we take Dana Thomas’s book Fashionopolis seriously (and I think we should), the clothing industry is responsible for at least 10% of global carbon emissions, 20% of industrial water pollution, and the other statistics are even more depressing. Fashion is the concept in the clothing industry that drives this engine. My feeling is that we must examine and re-think the relationship between democracy and capitalism to encourage more sustainable lifestyles. I once met and had a conversation with Robert Rodale, one of the founding fathers of promoting organic farming in the USA. We were talking about the biblical idea that humankind should have “dominion” over nature. “Well,” he mused, “you have to remember that Nature always bats last.”