Brendon Babenzien with his wife, Estelle Bailey-Babenzien, and their daughter, Sailor.

Aggressiveness often softens with time. It’s students who protest; young people who start bands and throw bricks. The older people get, the more likely they are to have settled into a niche, even in systems they’re not comfortable with, and the more they may have at stake in maintaining the status quo.

Brendon Babenzien has another perspective. After years as creative director at Supreme — as it grew from a clubby skate shop with a small in-house clothing line into one of the biggest brands in the world — it was fatherhood and the state of the world that drove him to launch his own line, Noah, in his 40s. And to run it his own way.

“Becoming a dad changed how I view clothing as a product; it did not change how I dress.”

“Once you have a kid, you start thinking about their future. If I didn’t start a business that operated in a responsible way, I’d feel like a terrible father. Her future is gonna be affected by the decisions we make, not just as individuals but in the businesses we operate, our environmental choices. It all matters.”

“Even my wife sometimes thinks I’m too hardcore. I view it as you’re on my team or you’re not. We no longer have time to be polite about it. Shit is bad. We blew it. We should have fixed things. We’re not left with a lot of time for niceties.”

Babenzien’s strong opinions show through in both the brand’s designs and how Noah frames them. Noah’s line includes Scottish-made sweaters and Italian tailoring, as well as graphic t-shirts that straddle the line between the type allusion-heavy prints Supreme specializes in and sloganeering. Noah’s made “Anti-Nazi League” t-shirts, and this fall dropped a t-shirt emblazoned with “Buy American” and an illustration in the style of mid-century magazine ads or children’s books. On a closer look, the shirt is not calling for A-Continuous-Lean-style domestic manufacturing — the only products in the illustration are sugar and cigarettes. You’d have to go to Noah’s blog or Instagram to find out the intent is to highlight the “evils that thrive in our culture.”

Their Instagram also has cost breakdowns on labor, fabric, and tariffs to explain the cost of their clothes, which is higher than mall-style retailers but lower than luxury/designer brands. I’d put it in the area of Todd Snyder, with tailored jackets at $500-$600 and sweatshirts around $150. Noah also seems to occupy an analogous place in the market. You could say Todd Snyder is for guys who grew out of J. Crew; Noah is for guys who grew out of Supreme.

Babenzien himself doesn’t dress particularly radically. He wears a lot of Noah designs that riff on traditional sportswear — rugby shirts, sweatshirts, weatherproof jackets — plus indigo denim jeans, Barbour jackets, and loafers. “The easy way to talk about it is, I have a fondness for traditional things, but I don’t have a fondness for what gave rise to the tradition, for forcing it on others: ‘either looks like this or you’re out.’”

I talked with Babenzien about how he arrived at his personal style, and he told me it took a long time, but eventually, his choices became natural and easy, rather than careful and considered: “I don’t really question my choices anymore.”

“I’ve been in this business for 33 years. Started in retail, moved into design — so I have this massive base of information, and of actual clothing. I have tons of shit. Ten to 15 years ago, I discovered I didn’t really want as much as I had, so I started really tailoring down what I owned. There are some very specific things I need to have. I need to have a Barbour jacket, for example. I don’t wear crazy shoes. I have penny loafers, and Doc Martens, and canvas sneakers. It’s actually really narrow.

“I respect dressing for the occasion — where am I going, who’s going to be there. There are times when you should stretch that, and times when you shouldn’t. Nothing wrong with adhering to guidelines that exist. If I go the beach, I’m going to wear fucking shorts, if someone says ‘We’re having an event and it’s black tie,’ I’m going to wear that.”

“You don’t want to leave good things behind; you just have to reinvent how people think about them.”

Menswear has been revisiting the concept of “classics with a twist” for decades, but no one is doing it better right now than Noah. The fall 2019 line includes oxford cloth button-downs, rugbys, a leather bomber, argyle sweaters, and corduroys. It leans preppy and sporty, but recontextualizes some of those references — one corduroy fabric is leopard printed; a deep pile fleece sweatshirt isn’t polyester but a wool/silk blend from Loro Piana. Last season Noah made a chore coat and rugby in bright floral prints.

“I don’t want to abandon things that look good. We can take things symbolic of a certain lifestyle and reappropriate them. The same way youth culture has always taken traditional clothing and made it punk. You don’t want to leave good things behind; you just have to reinvent how people think about them.”

Knowledge is a key factor in Noah’s designs, much like Supreme’s. T-shirt designs visually footnote albums, artists, and movements. Outerwear winks at old Ralph Lauren designs. But where Supreme is often intentionally vague about its allusions (Emily Oberg famously clowned Supreme lineups where customers weren’t aware of the artists Supreme was namechecking), Noah is often up-front. When Noah made a collection with Big Audio Dynamite in 2018, they published a piece and extensive photos explaining the relevance of the band to the brand. Right now they have a fabrics page explaining their choices, even down to fabric weights in grams per square meter.

Subcultural influences, especially music, infuse a lot of Noah’s designs. Babenzien has done runs of clothing with specific groups he grew up with, including the Cure, Fishbone, and Youth of Today. We talked about the strong, tidal pull of the soundtrack to teenage-hood. “You will never replace the music that influenced you as a teenager. You’ll have musical moments, but the music you listen from 13-20 forms you completely as a person. At that time, I was listening to music that spoke to me, who felt like an outsider.”

“When I talk to teenagers now — I know [being a teenager] probably feels like the worst thing in the world right now. But, do your thing. If you can survive that time, and understand that whatever negative thing happens during those years, get some perspective on it and turn it around? Those are the kids that turn out the best, more prepared for life. They’ve already dealt with sticking to your guns. Music helps you get through that stuff.”

Babenzien may have narrowed his closet down, but he holds onto the souvenirs of music. “The stuff I could never part with? Band t-shirts. These days it seems fairly obvious to talk about the Cure, the Smiths, etc. But that stuff really stuck with me. Getting rid of one of those shirts — it would feel like cutting off an arm. Now I go back to find ones I’ve lost over the years, vintage shirts.”

Making new clothes that function as merch for those bands works out for Noah and the bands. “Some of it is selfish. Those old vintage t-shirts are $500 now, but wouldn’t it be nice if it were $48?” When Noah makes a shirt, “It creates some newness for the bands. We get to create some really cool stuff. Bands get exposure to a new audience. Younger people potentially discover something they didn’t know about; they can decide whether they care or not.”

“I look at contemporary style heroes… it’s not gonna hold up.”

At Put This On, we often talk about the style of artists and musicians. Babenzien believes strongly in the link between lasting style and the cultural environment in which it flourishes — that good style is the smoke from the fire of creativity and newness. “Clothing doesn’t spring from something else that’s happening creatively? It doesn’t really have any legs, its just clothes. Same applies to clothing. Without a strong cultural movement, clothing has less meaning. I look at skateboarding and punk, rave culture, hip hop, surfing … I don’t see real true indications of culture in everything that’s come around in the last five years. Of course, I’m also older; it could just pass me by.

“It feels as if fashion itself is the thing now, it’s the culture. But fashion sprung out of other creative endeavors. Style always came from something else.”

Right now, Babenzien seems satisfied with what he’s been able to do with Noah since it launched four years ago — Noah now has two stores, one in New York and one in Tokyo, and sells through a handful of specialty boutiques, such as Dover Street Market and Union Los Angeles. Babenzien has a staff of about 30, and has striven to build a workplace that’s satisfying.

“If I feel great about it and everyone feels miserable, I failed. We don’t need to be the biggest clothing brand in the world. If we can support ourselves, make a product we love, create content that’s fun, build respect? The business doesn’t need to overwhelm us; I’m not calling you at home at 11 pm about a t-shirt.”

“Having a child completely changed the way I do this. If I act irresponsibly, it will have an impact on young peoples futures. Most people live with ‘I’m just doing the best I can, I don’t get to decide how things work.’ That’s not true for business owners. They dictate the behaviors of business. Through those choices, they dictate the use of resources. How people are treated. All of it. I have a choice.”

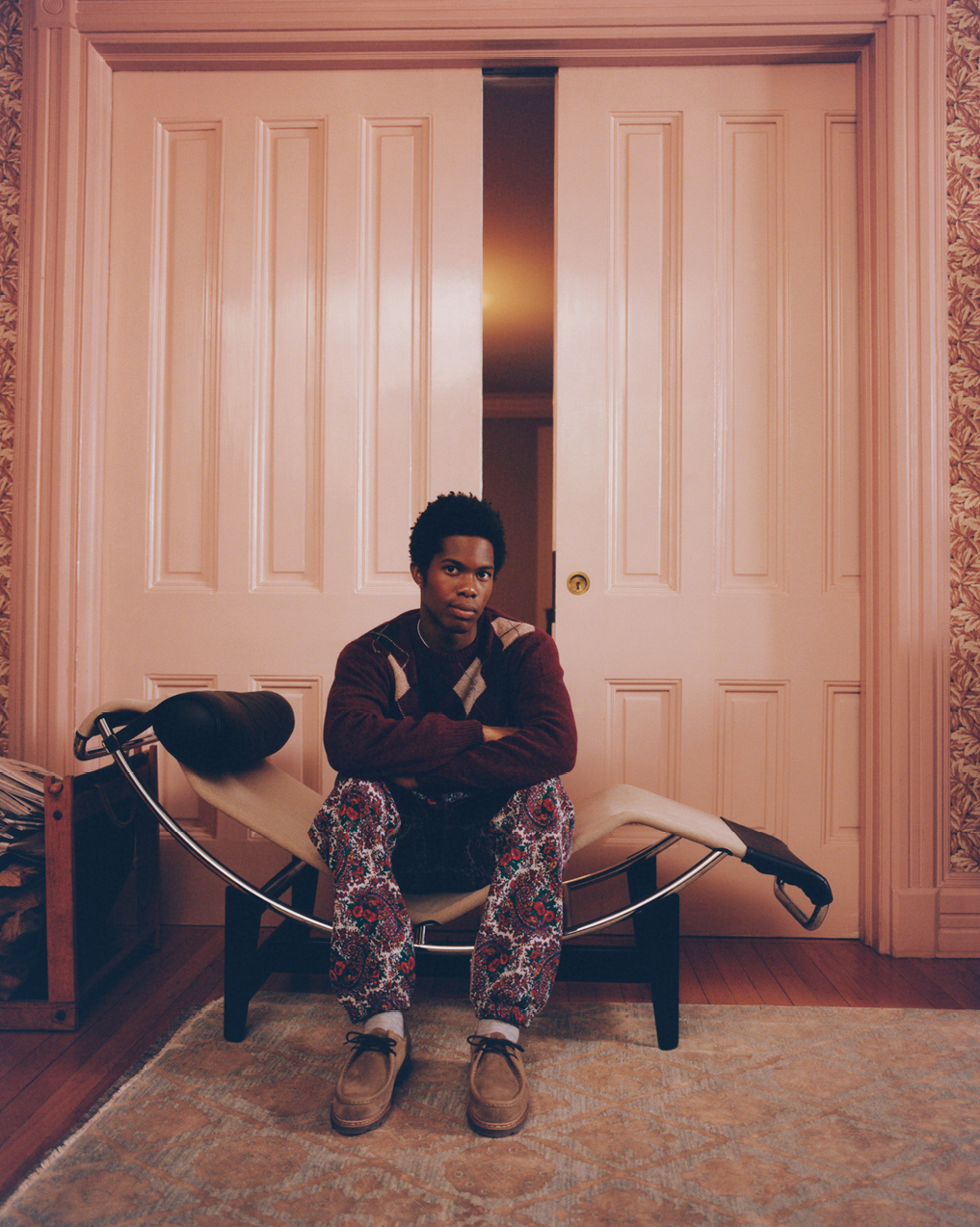

Images below from Noah’s Fall/Winter 2019 lookbook.