Sometime around the turn of the 20th century, social theorists split into specialized fields. The area of political economy, once integrating the fields of politics and economics, as it was discussed by Karl Marx and Adam Smith, became the two separate fields of political science and economics. Sociology also became recognized as an academic discipline in the US for the first time during the 1890s, with the University of Chicago establishing the first US department in 1892. Ever since then, academics have become increasingly narrow in their focus: studying how a specialized trade rule affects textile exports from Vietnam or how negative campaigning changed the outcome of two local elections in Paraguay, rather than coming up with grand theories about economic development and democracy, respectively.

David Marx’s latest book, Status and Culture, is certainly not the first book to try to come up with a grand theory about social outcomes. But it’s the only one that applies theories from sociology, anthropology, economics, philosophy, linguistics, semiotics, cultural history, literary theory, art history, media studies, and neuroscience to niche menswear matters, such as why we venerate Japanese selvedge denim and threadbare bespoke tweeds. To be sure, his book is about much more than menswear—it is a look at how our pursuit of status drives culture, including everything from our taste in music to our use of language. It’s one of the best books I read last year, so I caught up with him to chat about how his ideas apply to the changing landscape in menswear.

Your first book, Ametora, was narrowly focused on how Japan saved American style. This new book is almost the exact opposite in scope, in that it tries to explain how almost all culture happens. How did you decide to tackle such a big project?

I didn’t always write about clothing, and in many ways, fashion is quite a foreign topic for me. I grew up in Pensacola, Florida, and spent some time in Oxford, Mississippi, neither of which are particularly fashionable cities. My parents dressed us in Southern preppy style, so while I knew a bit about clothing, I wasn’t particularly into “fashion.” Growing up, I was very into college rock and alternative music; and later, I wrote a lot about technology and cultural trends in general. So when I wrote Ametora, I narrowed in on this specific story about menswear in order to have a case study on how culture is created and spreads.

Status and Culture tackles a broader subject, but it’s closer to what I’m most interested in. When I was in graduate school, I studied cultural theorists such as Veblen, Bourdieu, Everett Rogers, etc. I felt they were all telling different parts of the same story, but academic books tended to explain them as competing theories. So I wanted one day to show how they all work together to explain how the cultural ecosystem develops. And then Ametora tipped me off on specifics of how culture unfolds. I had always wanted to read a single book on “how culture works,” and Status and Culture is my attempt at explaining taste, identity, class, subculture, art, fashion, and history into one interconnecting system.

In fact, I think menswear gives us a particularly good lens for understanding how culture works—the origin of aesthetics, traditions, fashions, and fads, etc. When I was reading Bruce Boyer’s book True Style, I thought, “These lessons of how to dress are very much based in Old Money values and aesthetics—detachment, tradition, and knowledge.” When I had a chance to talk to Bruce about it, I asked him, “Isn’t this just Old Money style?” He said, “Yes!” You really can’t understand the origin of contemporary menswear without thinking about class, subcultures, and status. Additionally, since men are in such denial about their interest in fashion, you have many of the lessons of how people rationalize and obscure the reasons for their cultural behavior.

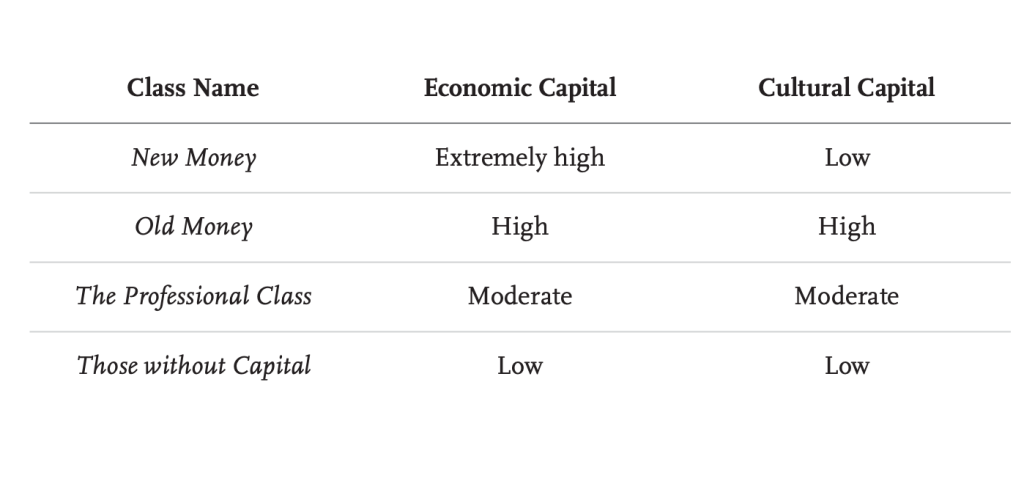

In your book, you define people according to four social classes, which you characterize as having varying levels of economic and cultural capital. And according to this rubric, people’s cultural behavior will be determined by where they fit into these categories. For instance, Old Money is high in economic and cultural capital, so they tend to value a kind of well-worn patina that can only be earned through generational wealth. New Money is extremely high in economic capital, but low in cultural capital, so they tend to favor flashier displays of status. And the professional class is moderate in both economic and cultural capital. Since they can’t compete with New Money in terms of buying flashy things, they pursue status by mimicking some of the customs demonstrated by Old Money, such as subtle displays of wealth and knowledge. Would you say that the heritage movement of the early aughts was largely about the professional class trying to pursue status and look Old Money?

Absolutely. First, I want to take a step back and define what I mean by “status.” I don’t just mean it as middle-class people trying to one-up their neighbors by purchasing increasingly expensive things. Status is about individuals’ rank within a social hierarchy and how each of those different hierarchies is ranked against each other. At a micro level, people in these hierarchies fight for better positions for themselves, and then at a macro level, they fight for their groups. So yes, this could mean trying to one-up your neighbor by purchasing expensive things—“keeping up with the Joneses.” But it can also include marginalized people fighting for dignity and equality, or one elite class trying to outdo another elite class by changing the rules of competition. It can also play out in artists trying to get their work recognized within the established art world. So status encompasses a much broader concept than just “why people buy fancy things.” I would argue it’s the scaffolding on which most culture hangs.

Now when we look at socio-economic groups, you’ll notice that they tend to signal in common ways. New Money people go from a low-status position to having a lot of money, which opens the door for potentially achieving higher status. So they convert the raw money into flashy, expensive goods, but they may not have the knowledge of exactly what to purchase to blend in within wealthy circles. When you look at the professional class, they have their own sense of superiority, where they feel they’re meritocratic winners and the rightful heirs of elite status in society. And they have an enemy right above them, New Money, who may have earned their fortunes through speculation or some other means that the professional class doesn’t deem to be legitimate. So both Old Money and the professional class don’t respect New Money.

Compared with New Money, the professional class has more cultural capital, which means knowledge about the culture associated with people in preexisting high-status positions. Thanks to higher education, they can be knowledgeable about art, music, literature, or how one should behave in certain privileged social situations. New Money often doesn’t have this knowledge. And so, if the professional class leans into this cultural capital, they can not only gain status for themselves, but in some ways, they can try to humiliate New Money for not having it. This means members of the professional class often gravitate towards status signals that show off cultural capital, which is to say cultural knowledge associated with their conception of Old Money institutions. Of course, this is all changing these days, since we live in a world dominated by New Money, but it explains a lot of 20th-century culture.

To bring this back to men’s fashion, when we look at American men, they weren’t generally interested in fashion during the 1990s. I think it’s fair to say that it was more or less taboo for straight men to care about clothes. Streetwear was one the first ways many men became interested in style because they were just wearing T-shirts, jeans, and sneakers, and streetwear provided elite versions of the things they wore anyway. The first big menswear wave came during the early aughts with the heritage movement, which let men justify their interest in style by saying they were dressing like their grandparents and re-engaging with tradition. American men started to embrace things such as Red Wings, selvedge denim, oxford button-down shirts, repp striped ties, Ivy style—all of which were a combination of Old Money and workwear.

Wouldn’t the workwear movement work against your theory? Workwear was historically associated with low-status groups, such as day laborers, not Old Money elites. Why would people in the professional class try to adopt the cultural aesthetic of day laborers, which in your rubric, is labeled as having low status?

This is one of the reasons why we have to be careful with how we think about status. Two hundred years ago, high status just meant wealth. The 20th century is interesting because we started to romanticize low-status groups that didn’t have much material wealth but seemed to be “authentic.” Elites used the styles from and knowledge about marginalized groups to elevate their own status position in society. This also happened with workwear, but it’s important to recognize that the aesthetic is always based in the wardrobe of an idealized laborer from a previous economic era. People are rarely copying the actual work clothes used today in society. Fashion fetishizes industrial labor at a time when service jobs are ascendent and industrial labor is in decline.

The obvious critique of your book is that you’ve reduced facets of culture to status signaling, which robs such things of their inherent quality. For instance, you characterize Old Money as valuing timelessness, thrift, and patina, which in your rubric, are just ways that they signal the highest level of status—generational wealth. New Money can buy a mahogany desk, but they can’t buy the well-worn patina of a mahogany desk passed down through generations. And the professional class values some of these qualities because they’re just trying to mimic Old Money and flex their cultural capital on New Money. But isn’t there something inherently good about being thrifty, valuing timeless design, and holding onto things as they age and patina?

Sure. I think there is some universal virtue in many of these beliefs and practices. But it’s hard to ignore the status component. For instance, some people say they thrift because it’s more environmentally sustainable, but that’s easy to admit that when we’re now in a time when they know it’s going to signal a virtuous behavior. Not so long ago, thrifting was not something upper-middle-class people engaged in for status purposes. In the 1980s, young people in Japan bought Comme des Garcon and Yoji Yamamoto second-hand because they couldn’t afford the new versions. Parents at the time complained that children must be very impoverished that they’re forced to buy used clothing.

While not everything is status, it’s counterproductive to ignore the role that status plays in so many cultural behaviors. To understand cultural behavior, you can’t really listen to everyone’s self-explanations. Culture is always about group behavior—and the average type of status signaling maps pretty well onto how certain aesthetics emerge from particular groups.

But as a group, Old Money comes from the people who stepped off the Mayflower, and those people derived their sense of aesthetics from Puritan values. Such people were never going to be flashy dressers anyway. They were naturally going to be thrifty, which meant passing things down to children. If we look at the sociological origins of these values, weren’t they once rooted in Christianity?

True, but if you look at late 19th-century robber barons, they were building very flashy monuments for themselves. Their children then took on Old Money aesthetics. These aesthetic shifts can happen very quickly, from generation to generation. Cultural beliefs tend to follow status signaling, rather than status signaling following cultural beliefs. No individual is condemned to certain beliefs because their ancestors were Puritans. The point of Status and Culture is to give people a field manual to understand how these dynamics operate to better understand these cultural behaviors and outcomes.

Your book explains how we got the heritage movement, but how do you explain its death? Why did the professional class leave the Old Money aesthetic?

Many of the signals associated with the look eventually became so ubiquitous that they no longer represented any form of elite knowledge. For instance, in the early 2000s, Thom Browne came out with the shrunken suit as a response to the sloppy aesthetic of the 1990s. At the time, many men were still wearing these baggy, overly-long pants that pooled around their ankles. So by coming out with slim fit, cropped pants, Browne was offering a stylish negation. This made slim fit into the elite signifier. But eventually, slim fit becomes the norm, and the only place to go is back to baggy again. That’s where we are with the wide pants trend.

That sounds like a fight within the professional class, not necessarily a fight between the professional class and New or Old Money. Which perhaps speaks to some of the diversity within these groups. In other words, it’s someone in the Creative Class not wanting to look like a boring lawyer or middle manager.

Yes, absolutely. And not wanting to look like latecomers to the movement. I remember seeing the big fits starting to show up in Popeye magazine about six years ago, and at the time, Mister Mort was saying skinny pants are out, and big pants are in. I remember reading that and thinking, “Ah ha, the reversal is coming!” But it has actually taken a while to catch on; we’re not at full proliferation yet. One of the reasons why I think it has taken a while is that we don’t have a narrative for the big silhouette look; it’s just a counter-reaction to what was in style a few years ago.

The heritage movement caught on quickly because it had a great narrative: most men dress terribly and need to return to their roots. They’re not necessarily “into fashion,” per se; they’re just dressing like their grandfather. It’s like, “I’m not doing anything pretentious or ostentatious; I’m just getting back into traditional American clothing.”

There hasn’t been a narrative like that in the last few years. Baggy is just a reaction to slim fits; the rise of tacky aesthetics—Balenciaga, Grateful Dead t-shirts, clashing patterns—is a counter-imitation of minimalist clothing. So there can always be different sources of cultural change—different proposals of innovation—but there needs to be a reason to get people to abandon one thing and adopt another. A lot of fashion right now is just a counter-imitation of what’s popular, and when it swings too much towards the extreme ends of the spectrum, it makes things too openly look like fashion. There are some people who will adopt giant chinos and layer really tacky shirts on top of other tacky items, but the lack of narrative around why we should all do this has made this a slower burn than the heritage menswear movement, which had an incredibly powerful story.

So is the Old Money aesthetic dead forever? Or do you feel it will return once streetwear gets saturated?

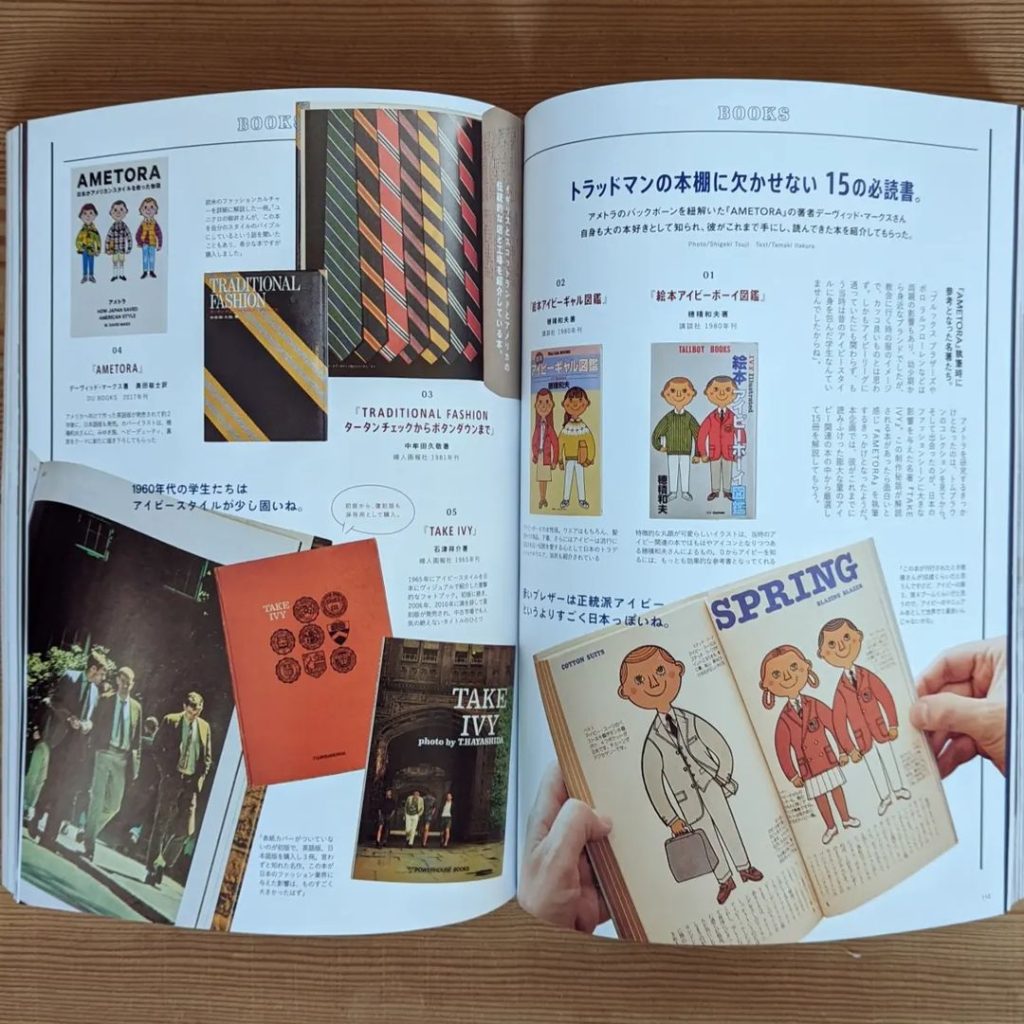

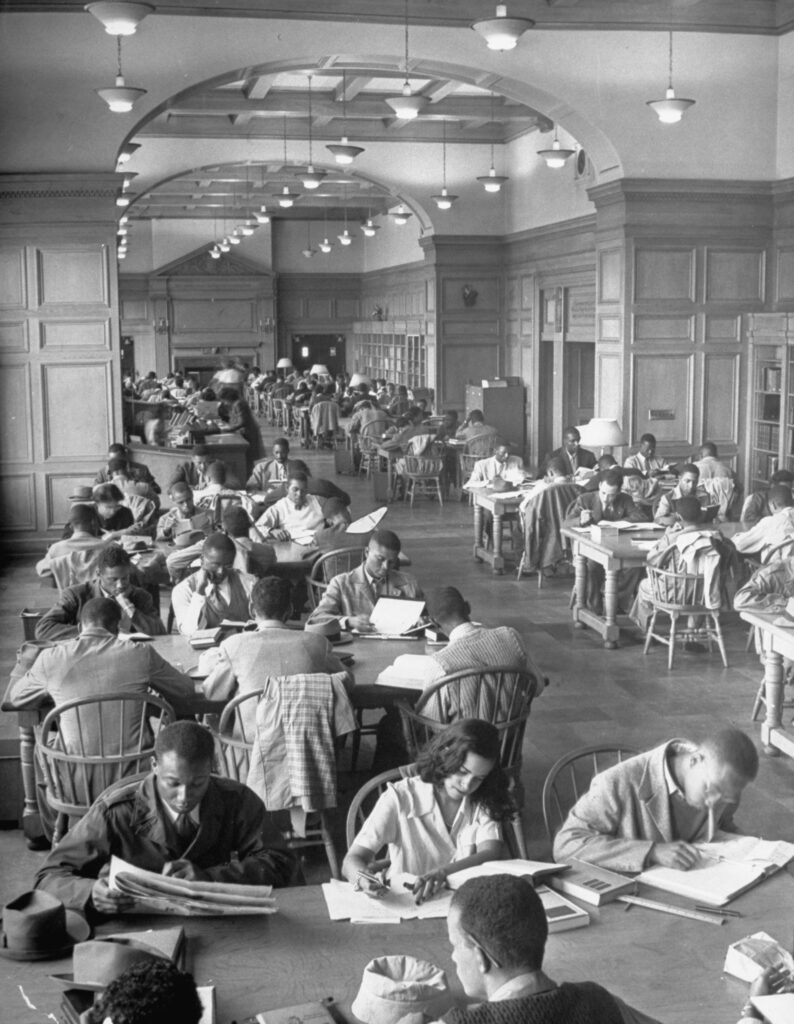

There are some things that are just not going to go away. In the book, I start Chapter Nine about how the oxford cloth button-down started as a fad. It went away, came back, went away, and then came back. At this point, I think it’s just part of American tradition. Even though people of all backgrounds wear it—some of whom we may not want to be associated with—it has such overpowering associations with historical high-status figures, such as Miles Davis, JFK, and the anonymous students in Take Ivy, that I think it’s now just part of American menswear canon.

The other thing is that this Ivy style has had a very rich, vibrant culture. This is something I talked about in Avery Trufelman’s recent podcast series. Ivy style is not popular just because WASPs wore it, and we’re all in awe of WASPs. It’s been strengthened in the interplay of elite campuses, the set of Jewish tailors and clothiers who made these garments, the black Americans who made it part of their culture and gave it a sense of cool, and the Japanese brands who helped locate the original authenticity in it. So it’s really about how these different groups use these symbols to express their identity. Is there ever going to be a time when everyone wants to dress like George Plimpton? Probably not. But elements of that particular aesthetic will come back in a different form because there are some universal elements in the look: minimalism, understatement, shabbiness, etc. Skaters can wear oxford-cloth button-downs, too.

Why do you think a version of Old Money aesthetics survives in East Asia, but not the US? For example, maybe it wasn’t George Plimpton, per se, but people who were of George Plimpton’s social class used to be real style icons for guys who were obsessed with menswear from about 2007 to 2012 or so. But now that Old Money aesthetic is gone, even in the corners of the internet that used to be champions of it. All the discussion nowadays, even in classic menswear, is around flashy watches and colorful shoes, which isn’t Old Money taste at all. But weirdly, when I see Old Money aesthetics on Instagram, it’s usually from very small communities in Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Thailand. Why do you think this aesthetic has survived in East Asia, but not the US?

The first thing to understand is that this aesthetic came to Japan as a foreign import. The people in East Asia who ended up wearing it were unlikely to be from the original Old Money, East Coast communities. So Ivy style had to be deconstructed, repackaged, and explained to Japanese customers who bought it and loved wearing it “properly” as a way to signal their deep knowledge. The end result was that the Japanese brands and media preserved the look as a set of rules.

When this look came back to the United States about fifteen years ago, the people who adopted it were also not necessarily from Old Money communities. Despite being American, they were discussing the style in the same way Japanese people did, They were talking about an explicit set of rules and adopting the aesthetic not as the organic customs of a community but as a style move.

This is very different from how the original practitioners wore it in the 1960s or so. During this time, a student would have gone into a university shop to purchase light blue oxford cloth button-downs, Shetland sweaters, blue blazers, chino pants, and camp mocs because those are the things the clothier sold. It was just a natural outcome of the environment.

Once these become style moves, people are prone to moving on. If you got into menswear through American tailoring, you might have moved on to British or Italian tailoring because you see it as more advanced. And you have to keep pace with other menswear trends—such as maximalism or minimalism—which will impact how you dress.

In Japan, there’s a group of people who are really into American trad, and they don’t alter it very much because they see the rules set in stone. They are fanatical about this look. My sense is that these Japanese communities have influenced other people across East Asia. My first book, Ametora, has sold the most copies in China, and it’s doing very well in South Korea. There are people in these places who are very interested in American trad, but they’re approaching it very much with the Japanese mindset (or alternatively, mixing it with streetwear).

The other thing to note is that suits are still part of daily life in Japan and South Korea. There are still men who go to work in suits, and so there are still the clothiers and tailors who serve this segment of the market. And since you see so many people in suits every day, there are going to be fashionable people who think about expressing their fashion sense in suits rather than just through T-shirts with logos.

What’s the media climate like in Japan? Are there still blogs and online forums to discuss classic men’s style? In the US, both of these things have all but died, which has impacted how easily one can learn about these aesthetics.

There aren’t many menswear blogs in Japan, but magazines still command a strong position. Men’s Club just celebrated its 68th anniversary; a lot of young people still read Popeye. I think this is the difference between the US and Japanese menswear scene. In the US, a lot of that movement was driven by blogs, whereas in Japan, the energy came from magazines. And there are still Japanese magazines that talk about trad. Some are specifically about that topic, while others cover it every fourth issue or so.

The most interesting chapter of your book is the last one, where you give a theory on why culture feels stuck right now. Part of that chapter is about how status games are very different now with the internet, where things that are cool can become uncool in a matter of hours. As a result, nothing really takes hold, so we get fleeting fads instead of era-defining trends. As I was reading that chapter, I found myself agreeing because you were talking about culture at large. But when I think of menswear, I can think of some important trends in the last twenty years. Just in this conversation, we talked about the rise and fall of heritage menswear and the Old Money aesthetic, the rise of streetwear, and how things have moved between slim and wide fits. Eight years ago, if you were to walk through downtown San Francisco, you’d see a dozen guys in joggers, black lambskin double riders, and Chelsea boots. Now it’s all about chore coats. Don’t these things mark eras in menswear culture?

I agree there are micro and macro trends in menswear. The macro trends have been very resilient, partly because we hit year zero in the 1990s, when men were so uninterested in style, you could create a major moment by just the revival of “style” itself. So if you go back to the early 2000s, you have the hipster skinny jeans moment and heritage menswear moment, both of which I think will mark their era. We’ll also look back at this baggy, maximalist, intentionally tacky era as a “thing.” As these macro trends emerge, they set the horizon of choices for men.

However, these changes are much less extreme than what we saw in the 1950s, 60s, 70s, and 80s. For example, when you go back and watch episodes of Friends, the styles are vaguely uncool, but you still know people who dress like that. At this point, the menswear scene is a relatively small community—it’s not the total population of men—which means they can’t create society-defining trends; you just get trends in menswear. And a lot of the trends are simply revivals of classic pieces. A chore coat, for example, is not a shocking fashion statement that we’ve never seen before. If you saw someone who’s not into menswear wear one, you might think it’s a cool choice, but it’s not a terribly surprising or upsetting choice. The reason why we remember the fashion choices of the 1950s, 60s, 70s, and 80s is that they were new and extreme choices that often upset a lot of people.

Doesn’t the early 2000s slim fit silhouette and J. Crew’s giant chino represent two extreme pant silhouettes for men?

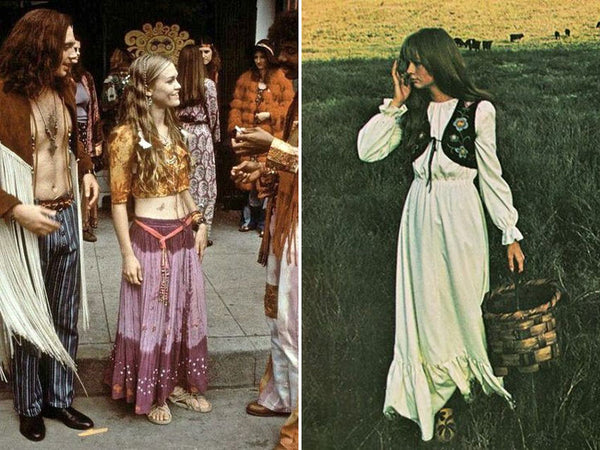

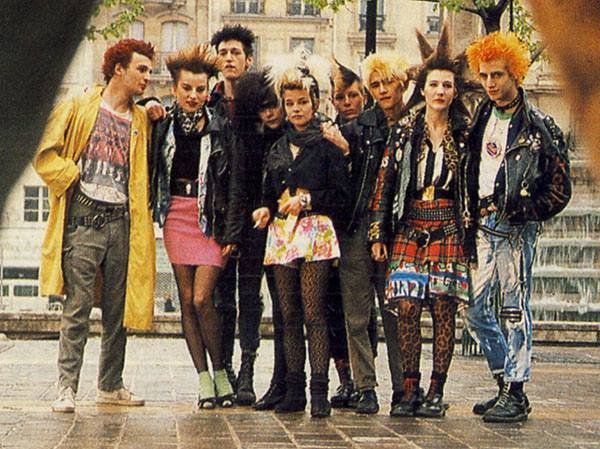

I agree, but those are still jeans and chinos, and are often worn in conventional ways. Compare that to how 1960s Ivy, 1970s hippie, and 1980s punk were huge shifts. Granted, those were not the same groups of people throughout that period, but each of those groups defined their era. People who are interested in menswear now can look back and say, “Oh yeah, skinny jeans” and “Oh yea, big chinos.” But does the average person think about the early 2000s as a different period because of the narrowing pant width?

When you say culture is stuck, does that mean we’ll no longer see innovation?

No, I still think there’s a great possibility for innovation. We’ve given more people than ever in history a chance to participate in the creation of culture. For instance, in the 1990s, you could make a film in college, but it wouldn’t really be seen by anyone because you had to get it into film festivals. Now you can just post it online. The same is true for music, art, and even clothing brands. So there’s still a lot of innovation, and I think that’s great. The question is, why don’t we feel like we’re living in an era of innovation?

My take is that it’s because a major source of cultural value is status value. We don’t want this to be true, because we’d like to think that things have intrinsic aesthetic value or some sort of communal value that transcends status value. But status value just infects the way we think about things. And in Chapter Ten of Status and Culture, I show how the particular status relations created by the internet have all conspired to deplete status value.

If you create something and nobody interacts with your ideas or creations, then they are more or less dead. Culturally, we have too much stuff in motion now. As a society, we’re not willing to all move in one direction and engage with the same things, so it’s difficult for us to create a narrative about what’s happening. Immanuel Kant pointed out that geniuses aren’t geniuses unless their ideas go on to influence society. So unless new ideas are popping up and inspiring wider movements, we may feel like culture is stuck.

Many thanks to David for taking the time to speak with me. Readers can order his books Ametora and Status and Culture on Amazon. You can also sign up for his newsletter, CULTURE: An Owner’s Manual.