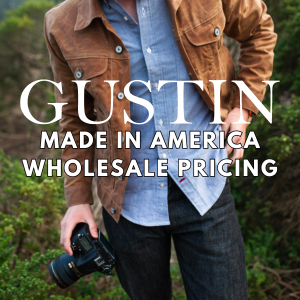

Norman Rockwell’s “Freedom of Speech,” painted for the U.S. Office of War Information, 1945.

Say you’re at your grandparents house, and you’re in the bathroom washing your hands, and you notice a framed print on the wall. Maybe this one. It’s sentimental; it’s comic in a grandparent-y way; it’s goofy. It’s well-executed and instantly recognizable, even without the signature, as a Norman Rockwell painting. When you see a Norman Rockwell print, what’s your first reaction? Do you shed a tear for a lost America? Or roll your eyes at borderline propaganda?

Rockwell’s Evolving Perspective

A prolific and talented commercial illustrator, Rockwell was probably America’s most popular artist in the middle of the 20th century, painting over 300 covers for the weekly Saturday Evening Post. His style was an exaggerated realism–real-looking people and situations but with a hint of caricature. Rockwell specialized in vignettes and characters familiar and comfortable for the Post‘s audience: white, middle class America. Mischievous children, buzzcuts and pigtails; handsome husbands and rosy-cheeked wives; kindly elders, adorable dogs. Often caught just before or just after a decisive moment: a sporting event, an argument, a hard day’s work, some sort of pratfall.

At this point, and maybe even at the time, Rockwell’s illustrations for the Post border on cliche or kitsch, although many are redeemed by Rockwell’s undeniable talent and keen eye, and a real sense of humor. Even as the body of work can be discounted as representing itself as slice-of-life America, while excluding large swaths of the American experience.

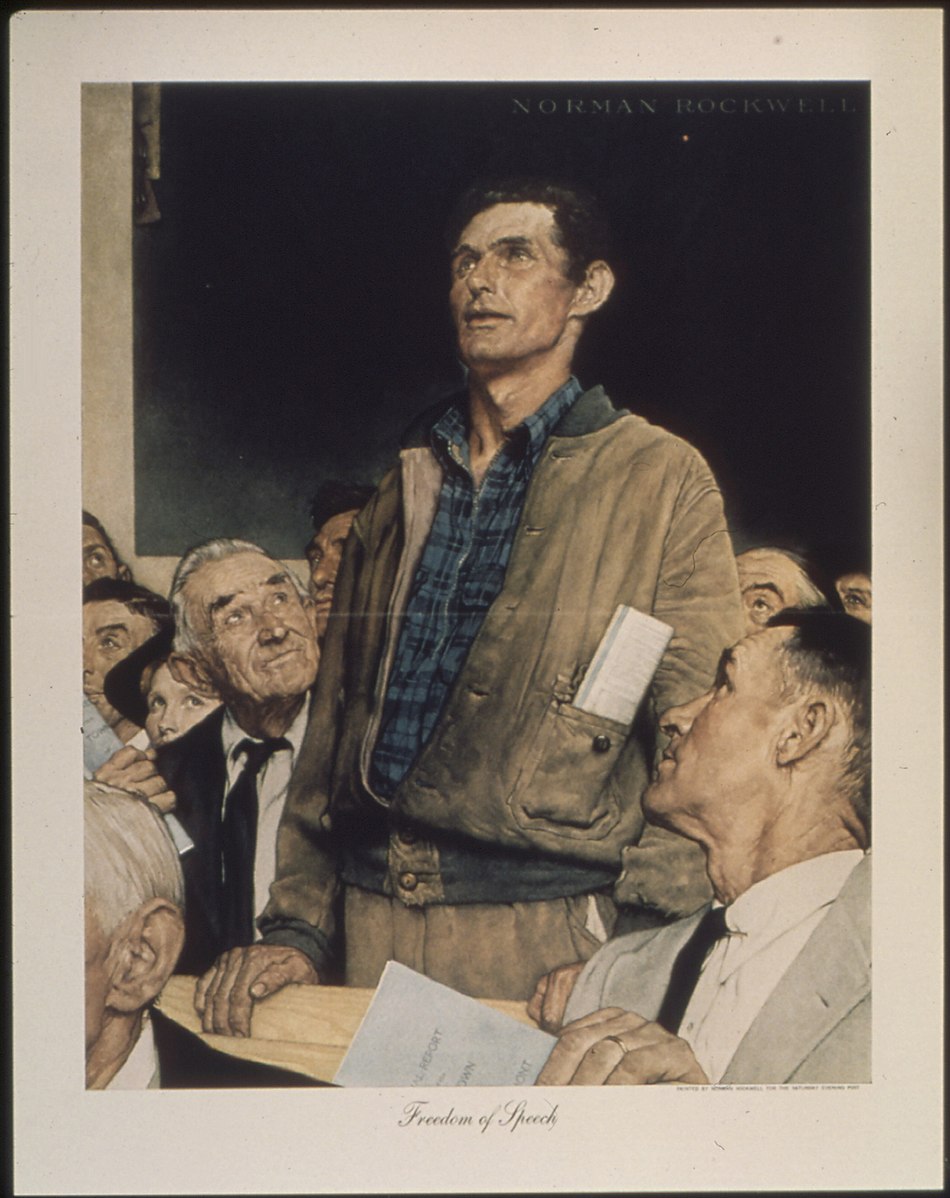

“Willie Gillis” was a character Rockwell’s work tracked through his experience in World War II. In this painting, postwar, he’s a student at Middlebury (note the stripes next to the window).

Later in life, Rockwell left his 50-year position at the Post (which by then was in decline) and did some work for Look Magazine. Vox had a great story a week or so ago on his political awakening at this point, when Rockwell, who had done many portraits of powerful people but focused largely on fictional or allegorical scenes, shifted gears and depicted powerful scenes from the civil rights movement. Maybe most notable is The Problem We All Live With, depicting a young girl being escorted by U.S. marshals to school during integration.

Painterly Denim Fades and Artist Style

Reading that piece, I realized I didn’t know much about Rockwell, including what he looked like, although I’d seen his well-known self portrait. Maybe it’s not surprising, considering that the clothes in his work were very specific and realistic, that he seems to have been something of a jawnz enthusiast.

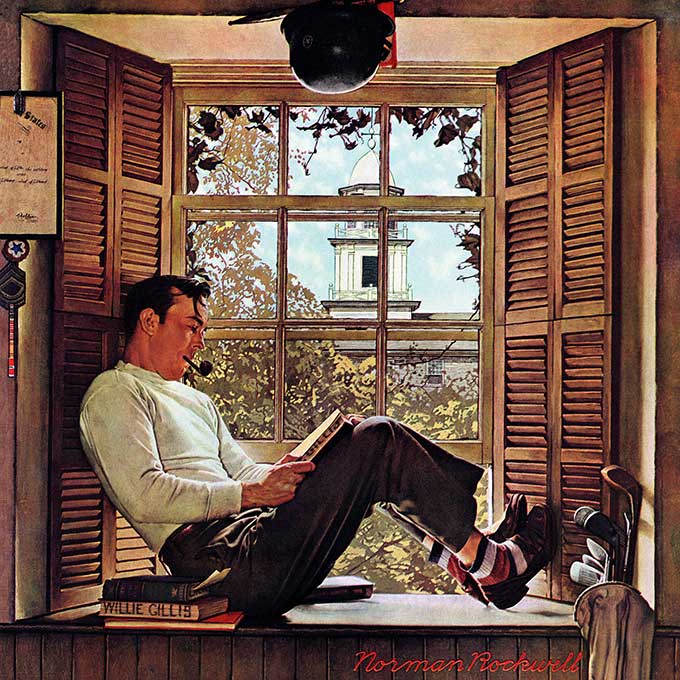

Typical of Rockwell’s humor, a runaway and a police officer at a lunch counter. Childhood mischief and benevolent authority!

His own clothing doesn’t fit neatly into our usual midcentury boxes of trad or prep, workwear or more dramatic, big-lapelled Hollywood tailoring. Truthfully, his own life predated a lot of those styles; at the outset of the 60s, he was already 66 years old. Rockwell was a Northeast guy, born in New York and spending his adult life in New England, and he seemed to combine some of the idea of northeast propriety — wear a jacket, cover your neck — with the workwear of a practical artist: denim, aprons, boots. In contemporary photos of the artist at work, he wears patch pocket sportcoats with plimsols, has his cuffs folded back at the button. He wears sack suits and bowties. He even naps in tailoring.

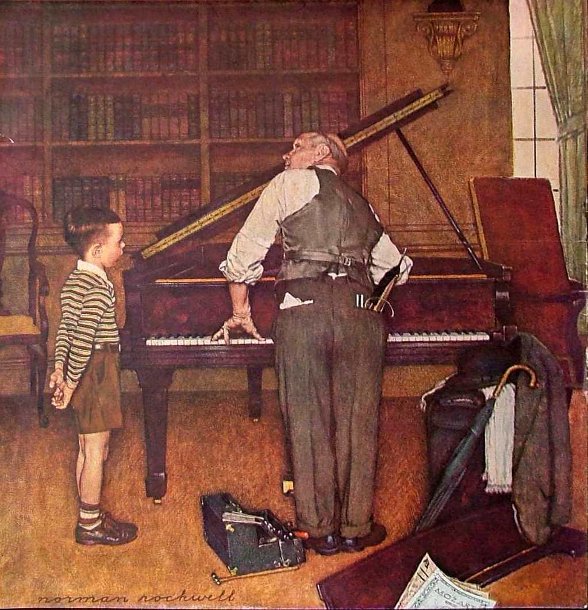

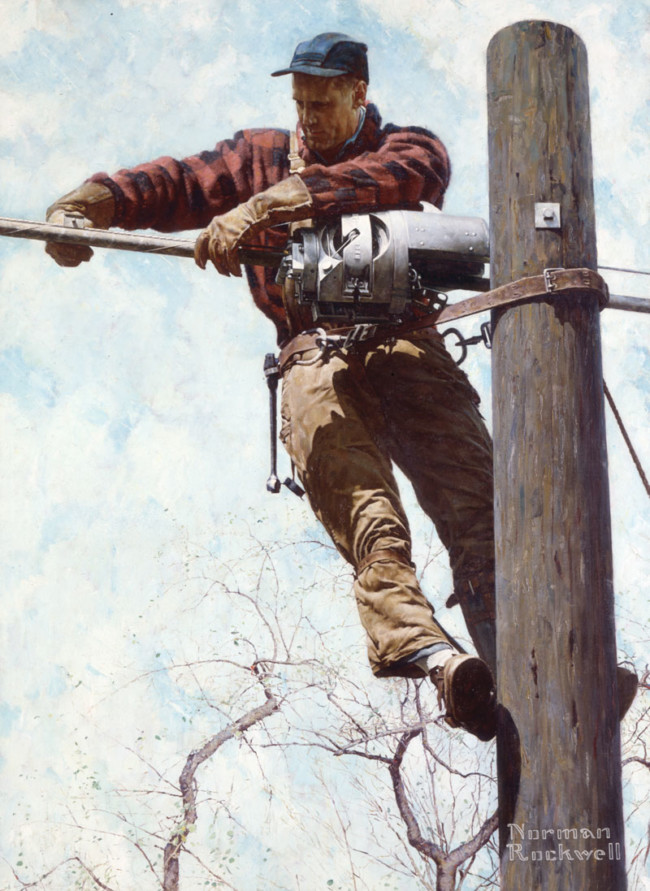

The clothes in his work receive the attention to detail anything in-focus in his art did; i.e., painstaking recreation. You could design an RRL collection off the references in his work, down to the pocket fades on the denim and the creases on the engineer boots. (Maybe it’s been done.) Having pretty much ignored Rockwell’s work as an adult in favor of art that seemed to say more or be more exciting, I really enjoyed browsing a few hundred Rockwell works looking for details — like the trousers on a piano tuner or the cap on a lineman — that wouldn’t necessarily have caught my eye in my grandparents’ bathroom.

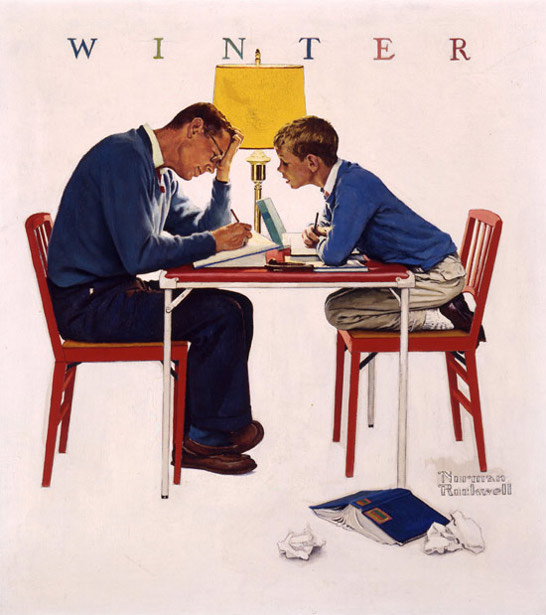

Blue sweaters and loafers for father and son.

The well-dressed piano tuner.

Rockwell often depicted the heroism of work.