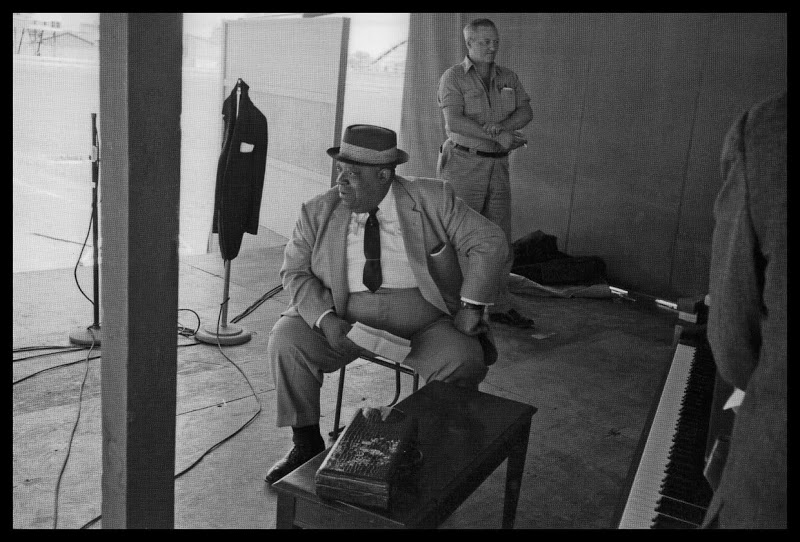

Eubie Blake at a White House celebration of the Newport Jazz Festival’s 25th anniversary, 1978.

Good style rarely happens in a vacuum — you can build personal style, but when it comes to icon status, you can’t really force it absent some other creative spark. More often than not, the best, more enduring style is an outgrowth of some other creative endeavor or scene. There’s a reason that many of the men we look to for inspiration are artists in some way — actors, musicians, painters. These people are more likely than the average guy to have a trained eye for proportion, texture, and color; more likely to have a performative streak and the flexibility to dress outside the expectations for everyday dress; and (this is a cliche, but) more likely to take appearance as another medium for expression.

The ever-quotable George Frazier, writing about jazz musicians and menswear, captured this truth pithily in 1960: “…most boutique customers should be lined up before a firing squad at dawn and there should be a minute of silence to thank God for the existence of people like Miles Davis.” For guys who like tailored clothing, in particular, the jazz scene’s style evolution in the 20th century is a rich source of inspiration. Jazz musicians often seemed to be leading the charge in terms of tailored style, especially when it came to the spread of ivy style.

To see how style evolved among jazz musicians, we often look at press and performance photos, album covers — professional photos taken in controlled settings. We see Miles Davis in OCBDs and narrow-lapelled jackets. Chet Baker in a cool polo in the studio.

Those photos are trying to sell us something, too. Not to take anything away from them, but LP covers want you to think the musician is cool as hell. Like brand lookbooks, they’re there to show their subject in the best light.

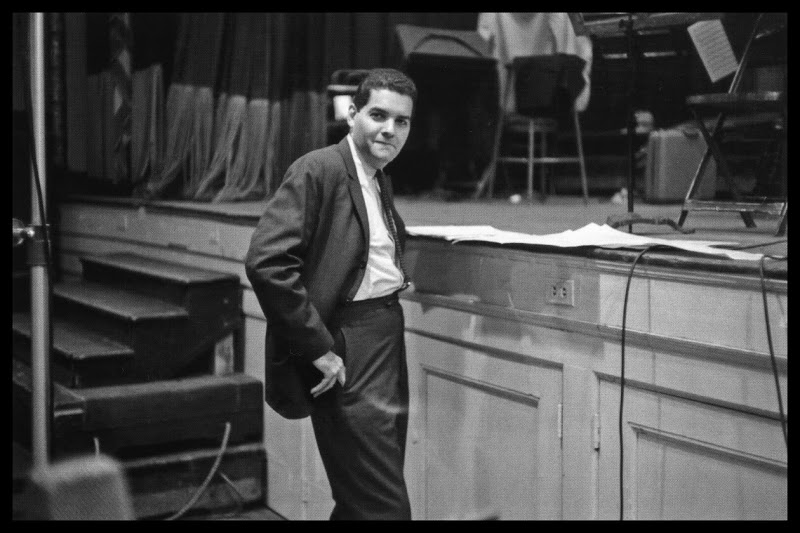

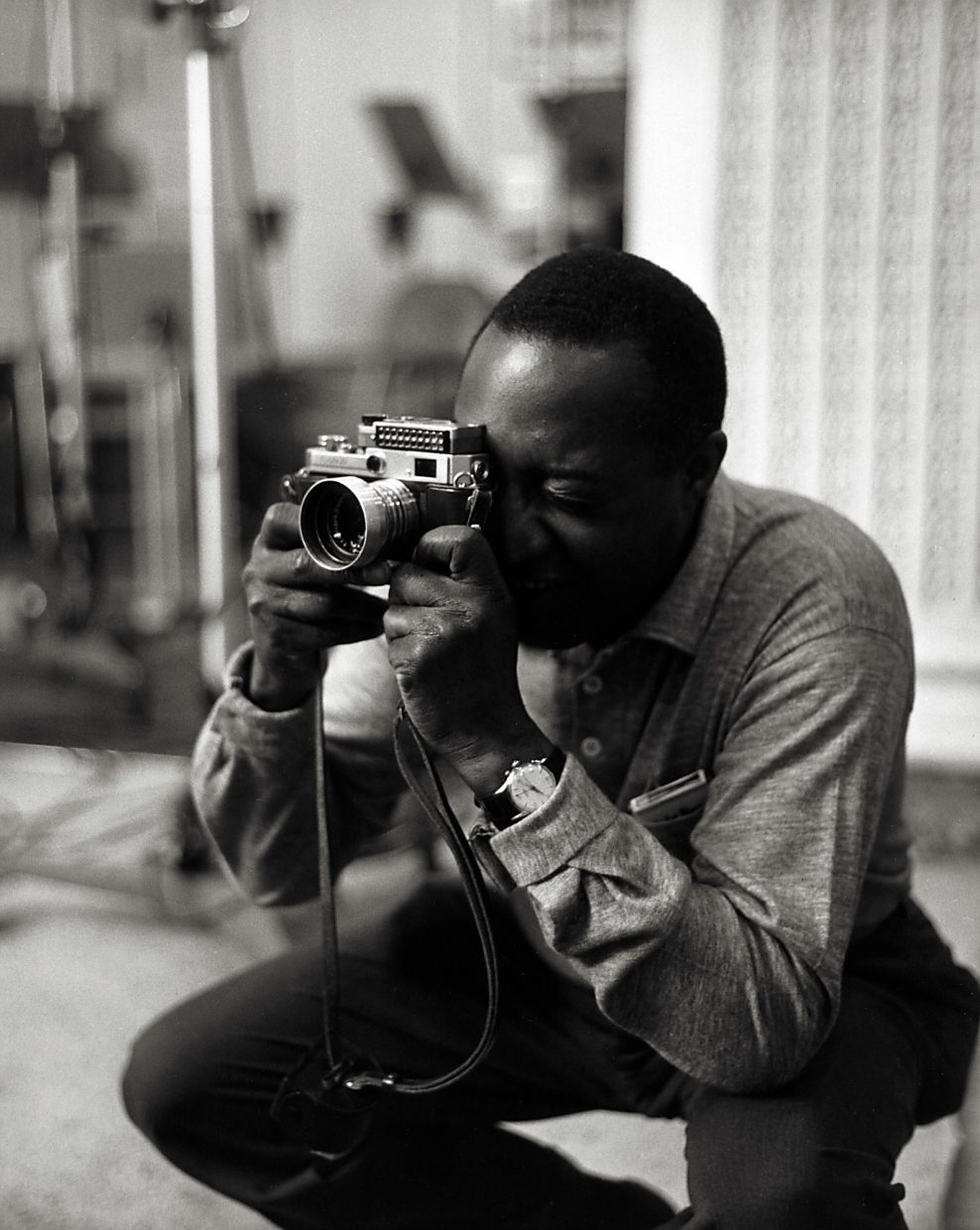

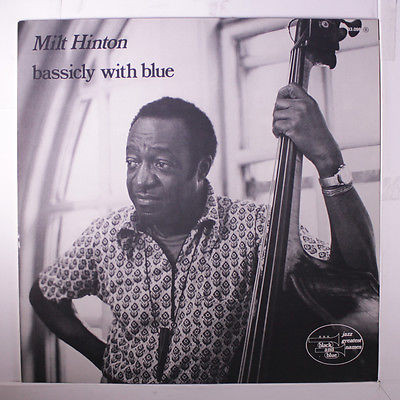

Another, more honest documentary resource is candid photos. Fortunately, one of the best bassists in jazz was also an excellent photographer — Milt Hinton spent 70 years playing with bands from Cab Calloway’s to entertainers’ like Jackie Gleason and Dick Cavett, to a session musician on thousands of recordings, including Bobby Darin’s Mack the Knife. All the while, he kept a camera (or two) with him, taking candid photos of his fellow musicians, fans, and friends.

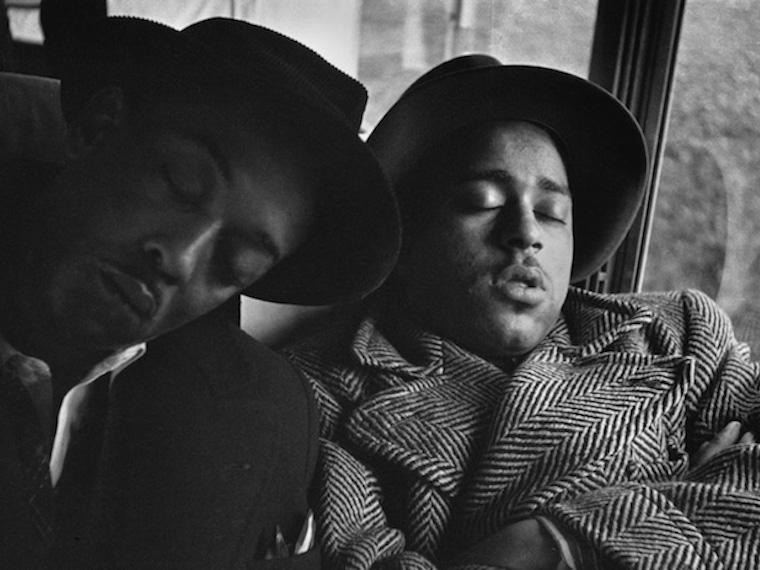

It wasn’t merely a hobby; Hinton was conscious of his craft. He usually shot without flash, so he wouldn’t bother other players. He shot almost exclusively in black and white. As a musician, he was allowed in spaces and at times that pro photographers might not be. Before his death in 2000, Hinton published books of photos and his work has been exhibited at the Smithsonian and Rhode Island School of Design; an institute at Oberlin College is named after him. Said Hinton of his photographs, “I always tried to capture something different. Whenever possible, I liked to shoot people when they were off guard or unaware.”

I admit I don’t know enough about jazz to give Hinton his due here, but he’s a legend, known for both steady time keeping and innovation, with a career that spanned the beginnings and end of many other jazz musicians’. He played the Cotton Club for years and still performed into the 1990s.

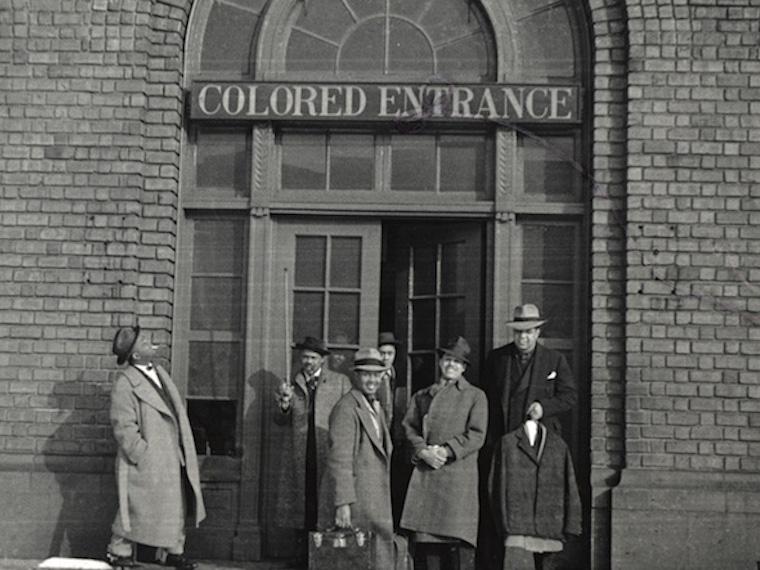

In Hinton’s mostly intimate, casual photo work, you see the baggy suits (and cool coats) of the 1930s and 1940s, the ivy style of the 50s and 60s, and the casual, theatrical styles of fusion in the 60s and 70s. Some photos seem almost Instagram-ready. From Calloway, to Dizzy Gillespie, to Billie Holiday, Monk, and Miles Davis. He shot candids on the scene of Esquire‘s famous 1958 shot of dozens of jazz players in Harlem. He also captured the Jim Crow world these musicians, who toured nationally to huge audiences, existed in when the shows were over.