Anderson & Sheppard’s new book, A Style is Born, is being released today. The 296-page volume is special in that it’s part of Anderson & Sheppard’s evolutionary shift, but to understand that, we should start with some history.

The company was founded in 1906, and originally called Anderson & Simmons. It changed to its current name, however, when Mr. Simmons sold his stake to Sidney Horatio Sheppard, a trouser cutter at the firm. Per Anderson, one of the original co-founders, was a Swedish expatriate who learned his trade from an innovative Dutch tailor named Frederick Scholte. Scholte is credited with creating the London cut (also known as the English drape), which is a term that refers to the way a jacket hangs (or “drapes”) from the shoulders. There is more room over the chest and shoulder blades, which results in conspicuous, but graceful, folds of cloth that gently descend from the collarbone. The uppersleeves are built generously, but the armholes are cut high, so that that jacket’s collar never lifts off of the wearer’s neck. The shoulders are also unpadded, which leaves them to slope naturally along the body’s lines. The combination of all these things make the English drape cut extremely comfortable and easy to move around in, but still adheres to many of the basic standards of fit that make a suit well tailored.

This cut was popularized by the Duke of Windsor, who wanted to rebel against his “buttoned up” childhood. The Duke longed for a more comfortable way of dressing – he often found himself removing his coat, ripping off his tie, loosening his collar, and rolling up his sleeves. It was a gesture not just for comfort, but also, in a symbolic sense, freedom. In Scholte, he found the perfect simpatico – a man who would make him a softly constructed jacket that would be as much about comfort as it would be about elegance.

Since the Duke set much of the early- to mid-20th century mens’ fashion trends, his implicit endorsement led to a boom in the cut’s popularity, which reached all the way across the Atlantic. Many Hollywood stars became enamored with the look, and since Per Anderson trained under Scholte, they naturally went to Anderson & Sheppard.

While Per Anderson built the house’s silhouette, his partner, Sidney Horatio Sheppard (better known as SHS), set its tone. In his introduction to the book, David Kamp uses a line from American satirist and Anglophile SJ Peterman. Peterman said of the British: “The expression ‘It’s not done’ pretty well sums up not only the state of mind of the more solvent class, but the attitude of people in shops and businesses.” SHS was apparently an “it’s not done” kind of fellow. He was a schoolmaster’s son, well educated, socially connected, and somewhat of a country squire. He was said to be very autocratic, not one to mix with the tailoring fraternity, and worked hard to build the firm’s reputation, but without making it seemed like the firm sought attention to itself. In fact, this was done to such an extent that the firm seemed almost secretive. While other tailors such as Henry Poole and Kilgour joined associations and guilds, Anderson & Sheppard never joined anything at all. Save for a single advertisement published once in an outdoorsman magazine, the firm also never advertised. SHS eschewed publicity of any sort and thought it was vulgar.

SHS’s reticence and strict sense of propriety filtered down to the staff, and this transmuted into a kind of hardedge severity. Women weren’t allowed into the fitting areas, unless they promised to keep quiet. Cutters were known to storm out of rooms if wives offered a suggestion or critiqued a husband’s suit-in-progress. They also refused to deviate from the house’s famous English-drape style. One cutter, Mr. Hallbury, would respond to such requests by saying, “Are you asking me to make a Rolls-Royce with the front of a Mercedes, sir?” A fierier cutter, Mr. Cameron, would simply show customers the door, saying, “You’re in the wrong shop!”

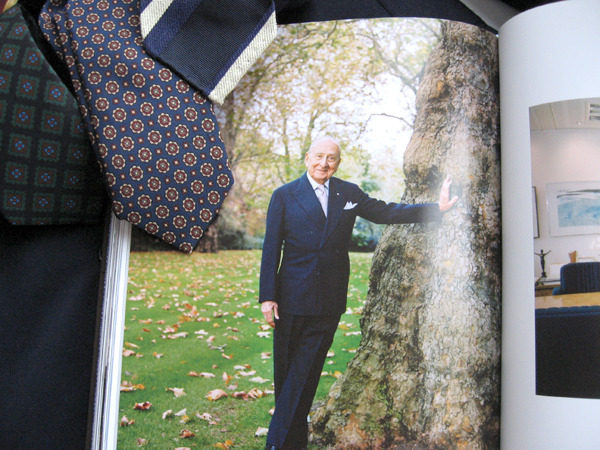

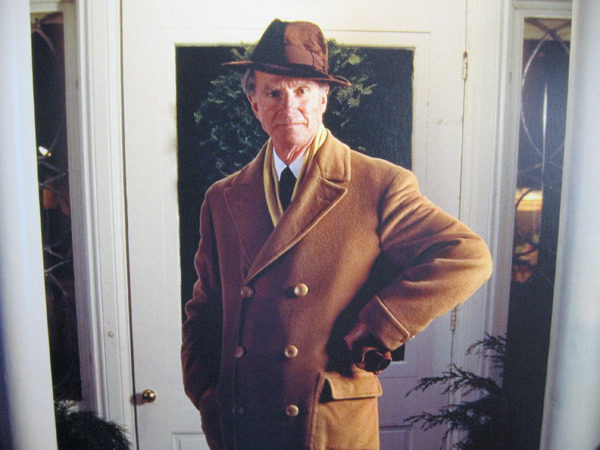

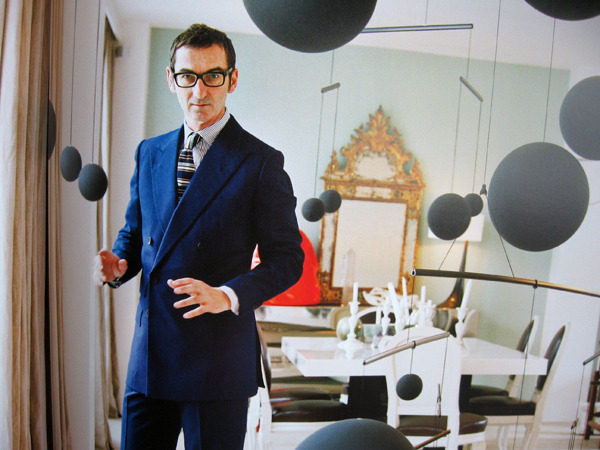

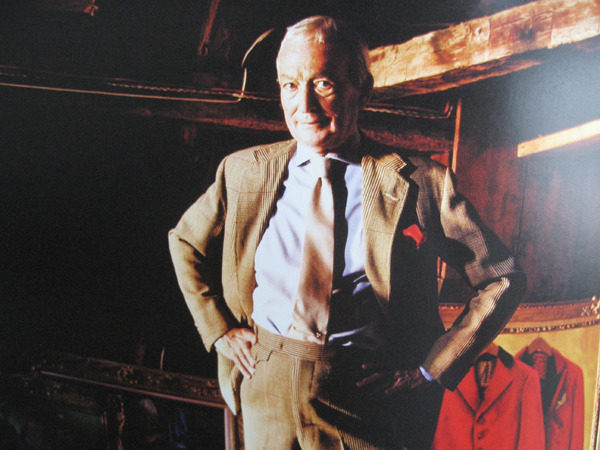

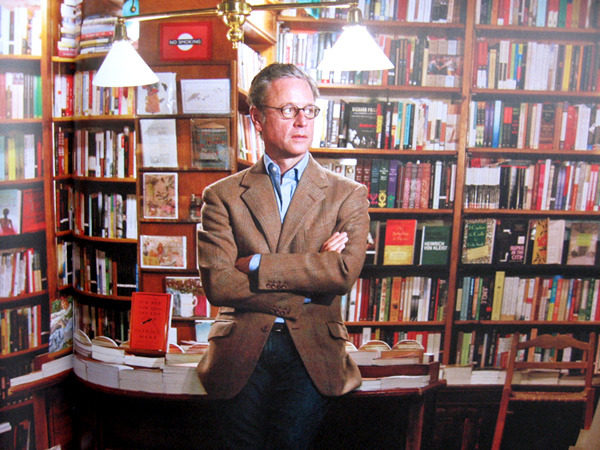

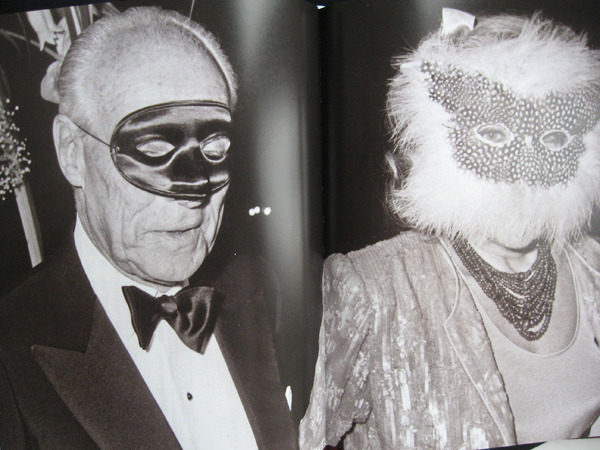

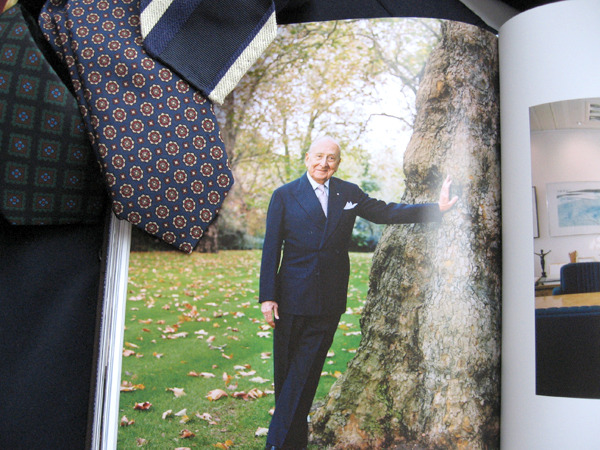

In 2004, Anda Rowland became Anderson & Sheppard’s vice chairman, and now manages it along with John Hitchcock. She has overseen somewhat of a glasnost there. The famously secretive house, once closed to writers and journalists, is now opening up. There is a website, a blog, and cutters and tailors who don’t mind your paying them a visit in the back rooms. The tailors are much friendlier, and no one is ever thrown out anymore (though they still won’t deviate from their cut). This book, then, is part of that evolution. The handsome photographs give a glimpse into inner workings and everyday details of life at Anderson & Sheppard, from the sturdily woven fabrics to the tailors’ and cutters’ workrooms. There are also sublime archival images of legendary clients of yore, not least of which includes Fred Astaire, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Gary Cooper, and Laurence Oliver. Nearly all of these men are photographed in their natural settings, and the elegance they portray is quite inspiring.

The volume is available for purchase on Amazon’s UK site, and I think it makes for a great addition to any library. It is part fashion history and part social history, and gives a near tactile immersion in one of the best tailoring shops in the world. I strongly recommend getting a copy.