Summer showers are soon to turn into chill autumn rains. Savor the smell of wet leaves and wool: it’s Barbour weather. But beyond the versatile (and borderline ubiquitous) waxed cotton jackets, you have plenty of options to choose from to keep the water rolling off your back. The best fit for you depends on just how water resistant you need your outerwear to be, your preferences for how a fabric looks and wears in, and what cuts/styles complement the fabric in question. Here’s your explainer for some of the fabrics and treatments you might see on new and heritage-style or vintage raingear.

Waxed cotton

The first people to wear waxed fabric rainwear were sailors who used linseed oil to waterproof sailcloth to cut and sew as rain capes (allegedly). The waxed cotton we see in Barbour-style jackets today is considerably softer and more refined than those, and its history as preferred cloth of gamekeepers and farmers in England makes it a good match for the tailored tweeds and shetland sweaters many of us favor.

- Pros: When the wax is fresh, it’s very effective. Arguably looks better with wear. Also quiet when you move, which is good if you’re trying to sneak up on a pheasant or coworker.

- Cons: Heavy. When the wax is fresh, it smells a little weird. Gets less effective with wear, and eventually it’s just greasy cotton that absorbs water. Most waxed cotton jackets aren’t cheap (Barbour, Filson), although affordable options are out there (Sierra Trading Post sales, LL Bean).

Ventile cotton

Ventile is a 100% cotton, uncoated fabric that’s very densely woven. When cotton gets wet, its fibers expand, making the weave so tight it becomes more water resistant. It’s been widely used in military garments, primarily in England. Private White VC makes some really good looking ventile jackets, as does Nigel Cabourn.

- Pros: Doesn’t necessarily have the “look” of rain gear, so it’s more versatile. Quiet. Soft.

- Cons: Not totally waterproof. Heavy and less breathable when soaked. Not cheap.

Bonded cotton

Another historical fabric, this one developed in England by putting a thin layer of rubber between two layers of cotton (modern bonded cotton usually uses a more breathable layer than rubber). For a long time it was considered the benchmark fabric for trenchcoats and macs.

- Pros: Has a reputation for being quite waterproof and durable. Particularly well suited to longer coats. Modern bonded cotton is at least moderately breathable.

- Cons: A little stiffer than ventile or broken-in waxed cotton (although that stiff, clean finish has its appeal). Expensive.

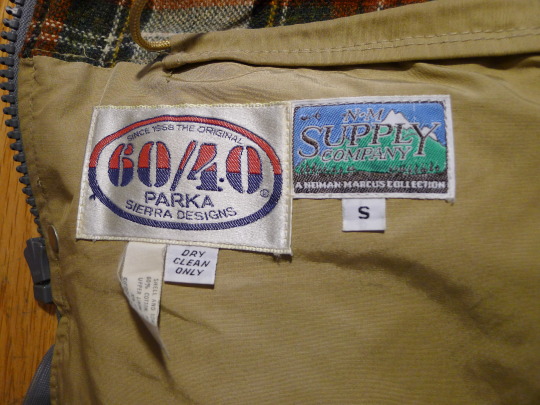

60/40 cloth

Developed by mountain climbers in the 1960s who wanted showerproof jackets with a soft hand, this fabric took advantage of modern weaving technology to create a 60 percent cotton, 40 percent nylon blend (often the blend isn’t exactly 60/40, but 65/35 or similar). Usually seen in mountain parka style shell jackets.

- Pros: Lightweight, not too expensive, comes in many colors.

- Cons: Leaks in heavy rain. When Gore Tex treatments came along, most of the climbing community moved on because of Gore Tex’s better performance in rainy conditions.

Rubberized fabrics

Rubberized cotton will not let water through. Although neither will a garbage bag, and it’s essentially as breathable. Still, the rubberized rain slicker has never gone away and will definitely keep the heaviest rain or sea spray off.

- Pros: Effective, can come in many colors, as cheap as you want it.

- Cons: Modern cuts, like Stutterheim’s, are pricier. Not at all breathable, i.e., you will sweat, and if you sweat enough, you’ll be wet anyway.

Gore Tex-treated fabrics (nylon/polyester, primarily)

Gore Tex is not a fabric itself but a membrane usually bonded between two fabrics in a jacket. It’s been the industry standard in waterproof clothing for decades because Gore Tex-treated jackets, when properly seam sealed, are legitimately waterproof and yet allow some vapor to pass through (hence “waterproof breathable”). Other proprietary fabrics have similar properties but Gore Tex is the go-to.

- Pros: Legit waterproofness. Can be applied to a variety of jacket styles, from North Face technical jackets to Visvim and Nanamica blazer-cut jackets (of which I don’t honestly see the point).

- Cons: Expensive. Can make a decent amount of noise when you’re moving, which really matters only if you’re trying to get close to wildlife. Most Gore Tex jackets are also treated with a finish that can wear off and make them less effective over time, although Gore Tex itself is quite durable and your jacket, left alone in the woods, will likely outlive you. Bummer.

–Pete

Lead photo via The Sartorialist