Having corresponded with Bruce Boyer for over ten years, I can tell you two things. First, he’s immensely kind, supportive, and gracious, despite my taking forever to reply to emails. Second, he often ends his emails by mentioning a book or an album he’s been enjoying. I’ve bought countless things based on his off-hand recommendations, such as Richard Sennett’s The Craftsman and Robert Graves’ The Long Week-End. I was also pleasantly surprised to learn some years ago that Bruce and I share the same taste in music, namely blues and jazz.

So, it was a pleasure to see that my favorite menswear writer recently penned something of a memoir about having seen some of the most influential artists during the 20th century. His new book, Riffs, is a collection of short essays reflecting on blues, jazz, and early rock and roll. There are some surprising bits of history, such as how Merck, the pharmaceutical company, once co-produced a blues album with RCA to promote an antidepressant drug. There are also some personal reflections, such as his chapter about seeing Nina Simone perform at a small Philadelphia venue, and, as you can expect, a bit about men’s style (such as insights into Frank Sinatra’s wardrobe).

When Riffs first debuted last year, I wanted to create a Spotify playlist to accompany an interview with Bruce. Fortune favors procrastinators, as Ivy Style contributor Eric Twardzik saved me the trouble and made a three-hour playlist on Spotify. It’s a wonderful way to enjoy some of Bruce’s favorite music (much like his style advice, his music recommendations are a step above the rest). I recently interviewed Bruce about his new project. Although the book isn’t focused on menswear, I think most readers will find that there’s a continuous thread running from clothing to other parts of culture, which we can call style.

You’ve spent the last 40+ years writing about men’s style, and while you approach the topic from a cultural perspective, the focus is typically on clothing. What made you want to write a book about music?

It’s true that, except for a little fiction and poetry, all of my writing has been about men’s style. However, during the COVID lockdowns, I found I had some time to try and stretch myself. I’d also been feeling for some time that I had written myself out about clothes, and I was growing stale and repetitive. At first, I thought I’d write some short stories, but I found myself listening to a lot of music. So, I started writing these little essays about what I was listening to and then circulated them among friends. After about six months, I noticed these essays were accumulating, and I wondered if I could make a book out of them.

While thinking about how I could turn this into a book, I reflected on what I wanted to accomplish. I realized that I could use my “memory history” to honor the musicians who have meant so much to me and perhaps introduce younger listeners to music they may find worthwhile. I chose to focus the essays on the musicians I listened to during that lockdown, but I could have easily chosen dozens of others who have influenced my youth.

I should add that music isn’t so removed from clothing and style. Many jazz and rock musicians were very stylish figures who were acutely aware of their image. Many of them even left their mark on fashion. In many cases, it’s impossible to separate the image from the talent.

It’s clear that your interest in music and style developed in tandem. I greatly enjoyed the stories of you going to dance clubs as a youth, as I also developed an interest in clothing in those spaces. Did your style evolve as you discovered different genres of music?

That’s right, the dancing and the clothes came together for me at the same time. I developed an interest in music early on, and by the time I was 15 years old, I had already tried the black leather motorcycle jackets and zoot suits that were prevalent in my blue-collar neighborhood. That look was more than a stylistic preference; it had an assertiveness that reflected an ideological position of the working class. Of course, the tough-guy clothes didn’t really work for a skinny little kid like me, so I switched to the Ivy look when I transferred to a high school outside of my neighborhood. That school had students from all over the city, and I noticed that the more affluent ones wore Ivy clothes, which I was aware was a symbol of discreet wealth in the form of unaffected understatement.

I remember when I was 17, I persuaded my mother to buy me an olive tweed three-piece suit for our junior prom, and then I persuaded several of the guys in my group to buy the same suit so that we could go to prom in these “uniforms.” I hope you don’t mind if I brag a bit, but I was a very good dancer and enjoyed a wide range of music—from Latin rhythms (Cha Cha, Mambo, Merengue) to jitterbug, and of course slow dances because you got to hold the girl in your arms. There are few times in my life where I’ve been happier than slow dancing in a smoky nightclub to a small band with a talented tenor sax player. It was the sort of thing that put the steam in my gabardine, as we used to say. I loved the club life, and in those halcyon days, people dressed to go to the clubs. One summer, I visited NYC and returned with a navy blue poplin suit from Brooks Brothers, which I believe was the first in our town. And I can tell you it was a big hit with several of the ladies.

Since there were three good colleges and a highly respected university within a five-mile radius of my home, Ivy clothes were a big part of the sartorial geography. There were three fine Ivy men’s stores for natural-shouldered tailoring, Shetland crew necks, repp striped ties, and all the other accessories. Later, they became video stores and pizza takeouts, but during my day, they were a tartan-carpeted, wood-paneled heaven to a freshman jazz aficionado majoring in English. I fear the tide is against me, as I continue to cling to that era with minimal change. I prefer small concerts to stadium venues, softly tailored clothes to overt costumes, and Koko Taylor to Taylor Swift. It’s my own little world now, but I’m content and comfortable here.

You noted in the book that many people see the mid-century as a period of “corporate consumerism, standardization, and the homogeneity of pop culture.” Yet, some of the best music—and fashion, I would add—came out of this period. We don’t typically think of corporatization and commercialization as being beneficial for cultural creativity. Why do you think the mid-century was excellent for music?

Some years ago I wrote a little book called Rebel Style: Cinematic Heroes of the 50s, in which I tried to briefly describe youth culture in the ten-year period after World War II. This may be oversimplifying, but I believe it’s true that American style, encompassing both music and clothing, diverged into two distinct directions following the war. People turned either to one version or another of Eastern WASP Establishment (i.e., upper-class Ivy college) or to underclass prole gear. In other words, there was an Ivy-jazz-intellectual nexus and a rebel-rock-blue-collar one. There were variations of this—I still would like to write a book about mid-century American style discussing the variations—but so many young, middle-class men who served in the military were able to receive a college education because of the G.I. Bill (officially known as the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act). Such people took up Establishment mores and became a version of The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit. However, many underclass White, Black, and Hispanic youths living in the inner-city were deprived of these opportunities. They created their own culture, which often revolved around music, zoot suits, and motorcycle gear. People who have studied these groups will tell you that the stylistic manifestations of what we may call the urban hipster, the rebels without a cause, and the so-called Beats were defiantly wearing their clothes as an exaggerated armor, both as resistance and denial of corporate consumer culture.

In reality, it is the underclass that often shapes culture. I’m reminded of the old saying that if you walk the same path as everyone else, you only see what everyone sees. Being out of the mainstream means having to construct your own culture. I agree with Leroy Jones in his study Blues People that Bessie Smith shouldn’t have had to sing the Blues. The reality is that she did, and the Blues is, in my humble estimation, the greatest gift America has ever given the world. Really.

But corporate consumerism has a way of surviving by co-opting even antithetical elements in society, and by the end of the 1960s, some young people were becoming aware that the clothes and the music had become tamed and sterilized. Today, we can’t escape the patina of commercialism. There’s a difference between Ivy and Preppy, as well as between the shitkicker engineer boots bought in Army-Navy stores and the purposefully distressed $1,200 Ralph Lauren version. The alienation and the aura of apartness are no longer there. Today’s rebel clothing may have the physical form, but it lacks the necessary “attitude.” In short, the icon-making power is gone.

In the book, there are instances where you establish a connection between the shifts in music and fashion, such as the transformation of jazz from a dancing crowd to a listening one (or the shift from swing to bop). As you put it, this transition coincided with the change from zoot suits to sack suits. I hadn’t thought about that relationship before. By the time rock-and-roll overtook jazz sales in the 1970s, it appeared that suits were already in decline. Do you think this is essentially a story about how jazz became too closely tied to the Establishment? Was it too intellectualized and not easy enough to dance to?

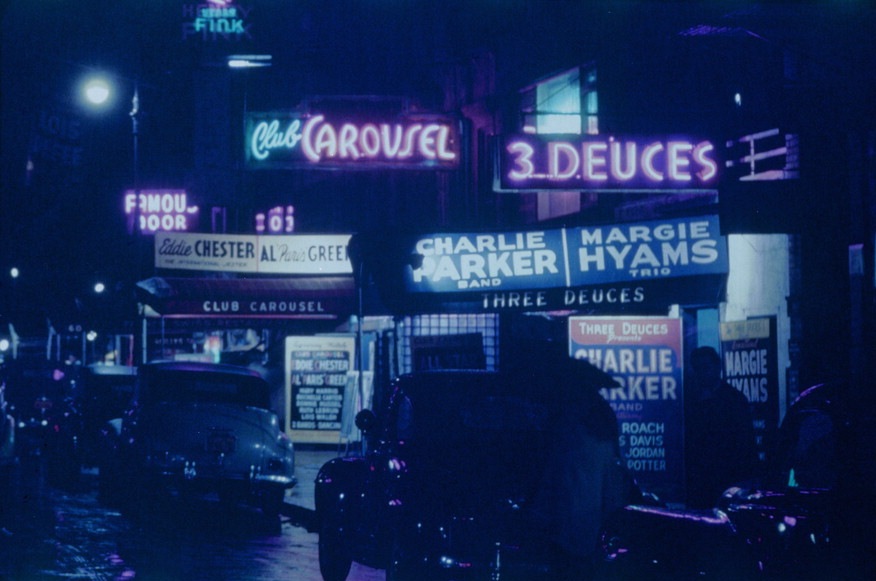

Jazz aficionados often tell the story of Black musicians becoming disenchanted with White bands ripping off their orchestrations. Supposedly, the great sax player Charlie Parker and a few of his friends decided to develop a new form of jazz and go where the White boys couldn’t easily follow. I don’t know whether this is true or not; I’m always dubious of easy answers to tough questions. However, we know that jazz transitioned from music suitable for dancing to music for listening, transforming from powerful beats and rhythms to intricate forms and sounds valued for their more introspective approaches. This new jazz was accepted by small numbers of people on both ends of the social spectrum. And the new jazz musicians who played to college audiences began appreciating the Ivy style they saw on campuses and took it home with them. That influenced the urban hipster to adopt a uniform called “Jivey Ivy,” which was an exaggeration of the campus look. On college campuses nationwide, parties featured rock music, while concerts featured jazz. Jazz was evolving into America’s classical music, a genre that people listened to attentively, studied, and pursued courses in. Perhaps because of its studious nature, jazz didn’t reach the popularity of rock, but its audience and the suit dwindled after the 1960s.

Did anything happen when Black jazz musicians started dressing Ivy? Did they help spread the style to new audiences at all?

Definitely. Black musicians got more and more gigs on college campuses after the war. The economics were such that the big bands were much more expensive than smaller trios, quartets, or sextets, so colleges hired the smaller groups. At the same time, jazz was turning towards smaller groups for expression, as big band swing music started to feel old-fashioned. By the mid-1950s, when these musicians were adopting the Ivy look, the handwriting was on the wall. If memory serves, Charlie Davidson of the Andover Shop dressed Miles Davis in a natural-shouldered seersucker suit to play at the 1955 Newport Jazz Festival. After that, every other jazz musician in the country went home and burned his zoot suits, if he hadn’t already done so. So the musicians spread the word to the inner-city youth that the Ivy Look was cool. That’s how it happened.

I’d love to have you react to a few music videos. Let’s start with blues because, as you wrote, that’s really the foundation for so much American music. Of all the blues musicians in your book, my favorite is Reverend Gary Davis. When I was young, there was a time when I was really into simple, acoustic folk and blues music because it felt very “of the people.” I still have a Charley Patton pin on an old Lee trucker jacket because I consider him to be the father of a lot of American music. In your book, you have an anecdote about how Merck, the drug company, once produced a blues album with RCA to promote an antidepressant drug. Why does this horribly depressive music feel so healing? And what do you think is particularly powerful about Davis’ music?

Rev. Gary Davis was one of my later discoveries; I bought my first album by him when I was in my 20s. The first time I heard “Death Don’t Have No Mercy,” my heart stopped cold. He’s a consummate guitar player who has the power to make his voice as deterministically harsh or as melodically delicate as he wants. There’s no gimmick here—no “show business” elements to pad out the performance. He sits in a chair and lets it rip with his guitar and microphone. Which means you immediately get that sense of authenticity, which captivates you. This is the foundation of blues and religious music. As Chris Strachwitz, founder of Arhoolie Records, is fond of saying, this ain’t no mouse music. If you want to confront the emotional truth of living, the Rev will bring it.

Albert Murray, one of the finest jazz commentators, argues that the blues help us cope with the blues. Blues isn’t about wallowing; it’s about helping us overcome sorrow and preserve. The blues tell us that tragedy is the way of the world, but we can heal with compassion and empathy. That’s why I titled that section in my book “The Camaraderie of Sorrow” and why Leroy Jones called his wonderful book Blues People. We can’t escape trouble, but we can gather around the campfire, share our stories, and feel a little less afraid and insecure. The blues skillfully transforms these overwhelming emotions into a comprehensible and relatable form, providing us with comfort.

You call Big Joe Turner your favorite blues singer. This is where blues starts to really feel like it’s forming the foundation of rock and roll. I would link “Shake Rattle and Roll,” but I think this clip of him singing “Honey Hush” is visually more compelling. Guys like him and Carl Perkins never really achieved Elvis’s success. Why do you think that is? And what do you like about Turner?

The answer to your question about the success of Elvis vs. Perkins and Turner—both of whom, and I know this is heresy in some circles, were superior musicians—is that Perkins simply didn’t have Elvis’ charisma. He wasn’t as handsome; he didn’t have the personal style; he just didn’t have that indefinable star quality. Turner, of course, was Black, and very few Black musicians were able to cross over into stardom for a White audience, regardless of how much talent they had. But both had careers that lasted much longer than Presley’s, so you could say that success is relative.

I first heard “Shake, Rattle, and Roll” when I was 13 years old. By that time, Joe Turner had already had a ~30-year career as a nightclub singer. He had recently signed a recording contract with Atlantic Records, and this was the label’s big attempt to cash in on the lucrative youth market by making Turner a rock ‘n roll star. So they put a rock band and chorus behind him. But Big Joe didn’t care; he kept singing the way he’d always done, with the force and ebullience that nature bestowed on him. People often refer to him as the “Boss of the Blues” due to his powerful delivery, yet I believe it was his joyful nature that drew audiences in. He makes us aware that sorrow will not conquer him. He will not surrender to suffering but instead go on laughing, loving, drinking, dancing, and fornicating ‘til they nail his coffin down.

I remember attending a house party in 1957, when I was about 16 years old. Couples were dancing to “Wee Baby Blues,” my favorite Turner song, with the rugs rolled back in the dining room and the lights turned down low. I’ve never forgotten that scene; it seemed at the time, and still does today, to have been life itself. A hero is someone who lifts us up, and Big Joe Turner lifts me as high as anyone could.

I admit I felt a bit of jealous envy when I read that you saw Nina Simone perform at Pep’s in South Philly. To me, she’s the total embodiment of American music, as she blended folk, jazz, blues, and even show tunes. But more than that, she was the musical voice of the Civil Rights movement. Later in life, she told an interviewer at Jet Magazine that the music industry boycotted her because of “Mississippi Goddam.”

In recent months, bands like Green Day have garnered backlash for taking a political stand. And during the Bush years, there was a boycott of the Dixie Chicks. People want their entertainers to stay away from politics, at least when they disagree with their views. During the time you watched Simone develop as an artist, did you see any similar controversy?

I saw Nina Simone near the beginning of her career. She had been playing clubs in Philadelphia and Atlantic City for a few years before she got a recording contract. Her version of “I Loves You, Porgy,” from the Gershwin musical, was the first song to make a splash with lovers of jazz and R&B. That was the first time I heard her, around 1957. The voice was so plaintive, the piano-playing so accomplished and full of soul, we were struck dumb. Simone had somehow combined her expertise of classical music with a blues feeling to produce something unique, and as you note, she continued to blend her classical studies with blues, folk, and show tunes. She was without question the hippest thing out there.

I think it was sometime in the late 1960s, possibly earlier, when I noticed she was no longer getting TV appearances and her records weren’t being played as much on the radio. And we knew why. She started to take a very insistent stand against segregation. She is another hero for me—someone who knew that she would jeopardize her growing career but did what she knew to be right anyway. She was a tremendous talent, and she used her work for the cause. She threw herself into that struggle and willingly paid the price, and I don’t think there was another example quite so striking.

I found your chapter on Frank Sinatra really fascinating, particularly in how you described Sinatra’s style changing over time. He went from wearing zoot-suit-esque tailoring and floppy bow ties indicative of working-class bobby-soxers to a sleeker, more urbane look of his Rat Pack era. Apparently, he even wore a bit of Ivy Style clothing during the 1960s. As someone born after this period, I hadn’t thought about how he was cutting against middle-class sensibilities at the time. To borrow Karen McNally’s phrase, which you quote in the book, Sinatra was the “antidote to gray flannel.” Could you elaborate on how these clothes reflected socio-economic class?

I should start by saying that Sinatra was always interested in his appearance. Even as a child, his mother dressed him very well, and as a young man in Hoboken, people nicknamed him “Slacksey” because of his extensive wardrobe. The style at the time—slightly before WWII and slightly after—among urban youths living in working-class, ethnic enclaves was some variation of the zoot suit, which was an oversized, flashy version of traditional tailoring. Suffice to say, it was underclass armor and a way to express alienation from middle-class proprieties. In a segregated Italian neighborhood, a young Sinatra could have been expected to take up this sartorial approach—and he did.

This look served Sinatra well when he ventured into the world of big band music in Manhattan, as oversized suits were part of the aesthetic of bandstands. But when his ambition took him to Hollywood, a lot of his tailoring lost its volume. Film stars favored the drape cut, which was only slightly oversized to accentuate the wearer’s masculinity but still telegraphed a certain kind of middle-class sensibility. Sinatra’s sleek era was then just on the horizon. By the time he started performing in Las Vegas, he and his Rat Pack were responsible for popularizing the “Continental” lines of their high-luster mohair and Dupioni silk suits. This style was also favored by both the owners and habitues of nightclubs, as well as guys who took their dress advice from Playboy magazine. The term was cool.

For a brief period in the late 1960s, Sinatra flirted with Ivy style clothing from J. Press. Richard Press, grandson of the company’s founder, has written marvelously about this. You can see this look in Sinatra’s 1965 TV special, “A Man and His Music.” Was Sinatra looking to telegraph a certain kind of mature respectability? Did he adopt it because Ivy was a popular American look? Was he influenced by jazz musicians who had also taken up the style? Yes to all of the preceding. Sinatra enjoyed clothes, and he picked up on the sartorial zeitgeist. In his final years, he dressed in Old Hollywood Casual, still preferring his mohair tuxedos to show a bit of white flash from his shirt cuffs. He went from one look to another—the money was the difference between them.

Finally, I want to ask a more philosophical question. You’ve spent most of your life writing about style, particularly as it relates to men’s clothing, but almost always through the lens of culture. This new book is just about music. Do you believe that exploring different perspectives on style can provide valuable insights into clothing? In other words, can one learn how to dress better by paying more attention to things like music, art, and film?

Well, I’m relying here more on gut instinct than analysis. I think my contribution, if any, has been to help people see clothes as part of the greater zeitgeist rather than things in and of themselves. I’ve always been a philosophical integrationist, finding it difficult to talk about anything as a separate entity. In my own life, I’ve found that influences come in armies, not as individual soldiers. My love of music, dance, and clothes all came to me at the same time. I can’t separate how they’ve contributed to my life.

For me, style is the common thread. Some guys have style, while others just spend a lot of money. It’s so interesting that two guys can wear the same thing—let’s say jeans, a simple white shirt, and sandals—and yet look totally different. One can look so right and the other so wrong; one so cool and the other so uninformed. A person’s style permeates his life, both describing him and informing us. Every aspect of it seems to tell us who he is, from the way he gestures to the way he folds a pocket handkerchief. We could even say that, on some level, stylistic preferences are ideological and moral positions.

If I may add, I’ve never believed that there is a right or wrong way to dress. Apart from giving some thought to the nature of the occasion, I’m more of a mind to agree with Thelonious Monk: “There are no wrong notes, only better choices.”

Many thanks to Bruce for taking the time to chat with me. Readers can buy his book on Amazon or get the digital edition from Alexandria Labs. There are also a few autographed copies available right now at St. Johns in Ridgefield, Connecticut. Finally, be sure to check out the Spotify playlist that Eric kindly pulled together. The songs are nicely organized according to their appearance in Riffs, making it a helpful accompaniment to the book.