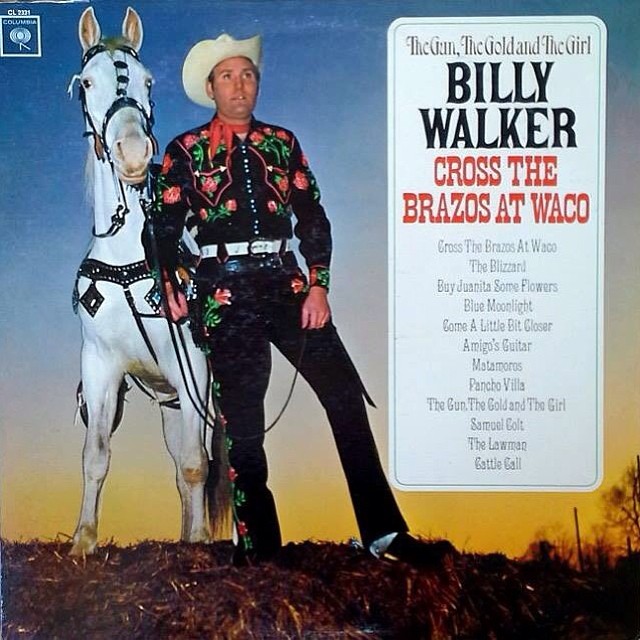

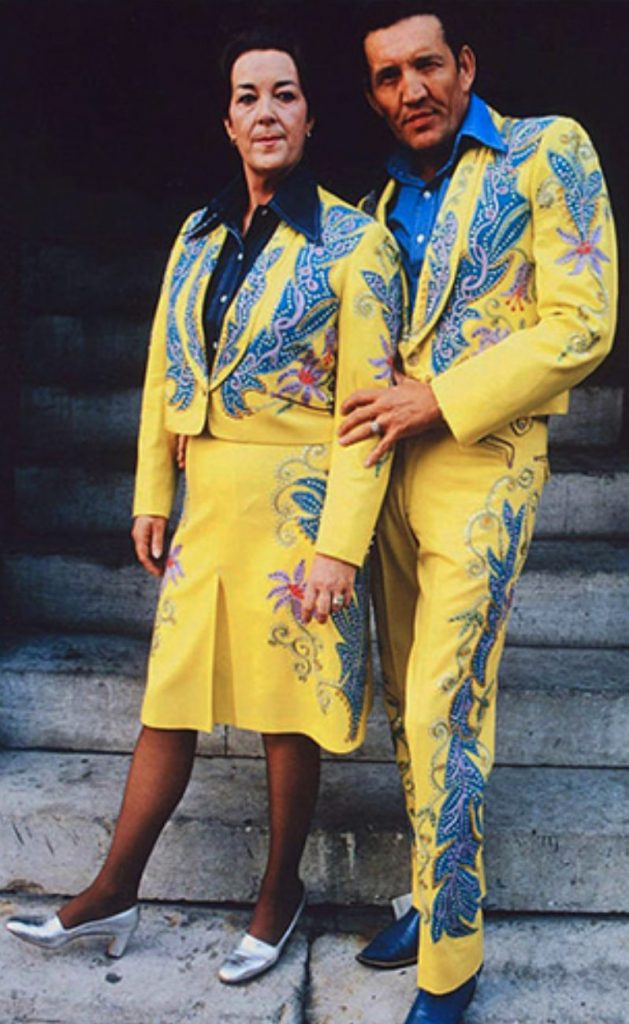

When I was young, I spent a lot of time in dusty, hole-in-the-wall record shops, rifling through battered milk crates and searching for discounted $2 LPs. At the time, I was obsessed with American folk music, including Delta blues, gospel, and Appalachian folk. I also adored mid-century country tunes, such as the twangy sounds of Hank Williams and Roy Rogers. While listening to those albums, I used to admire the preposterously gaudy clothes on their LP covers. These riotous cowboy suits, where rows of glimmering rhinestones could be found on every fringe, embodied a kind of American machismo that bordered on camp. Across the chest and sometimes down the legs, there were chain-stitched motifs reminiscent of traditional American tattoos — chirping birds with splayed wings, red-petaled roses, marijuana leaves, and giant Christian crosses.

In my young adult mind, I associated this aesthetic with white grandparents who collected delicate porcelain figurines and lived in homes where patchwork family quilts covered every surface. It was an aesthetic that I found charming but somewhat foreign, being a second-generation immigrant and son of Vietnamese refugees. I thought I was tapping into this “true Americana” that presumably had always existed in this country. I later learned that the tailor who made these clothes shared more with my parents than I could have ever imagined.

In December 1902, Nuta Kotlyarenko was born into a Jewish Ukranian family living in Kyiv, then under Czarist Russia’s rule and now the capital city of an independent Ukraine. He grew up in a poor but stable family. His father was a cobbler; his mother sold poultry. On weekends, Nuta’s mother worked at the local theatre’s concession stand to make extra money. Nuta remembers his mother telling him that America’s streets were “paved with gold.” And in 1913, when Nuta was at the tender age of eleven, his parents smuggled him out of the country, sending him to the United States to save him from Czarist Russia’s pogroms.

Like many immigrants who arrived on these shores, Nuta came with nothing. He didn’t even have his name, as the immigration agent at Ellis Island misheard him and wrote “Nudie Cohn” on his papers. When the young Nudie lived in Brooklyn, he didn’t even have shoes. He remembers a concerned teacher giving him a pair of mismatched boots one day after seeing his feet wrapped in rags.

As an adult, Nudie was an itinerant worker doing odd jobs. He was a boxer, film editor, and shoe shiner. He crisscrossed the country several times and was once arrested for drug trafficking, a crime that landed him behind bars for nine months. By the time he met his wife at a boarding house in Minnesota, he was on the straight and narrow. The two got married, had a daughter they named Barbara, and moved to New York City. They lived in a gambler’s hotel, where Nudie met the gangster Pretty Boy Floyd, with whom he struck a friendship. He and his wife also opened a shop in Times Square called “Nudie’s for the Ladies,” where they sold glimmering g-strings and lingerie to local showgirls and burlesque queens.

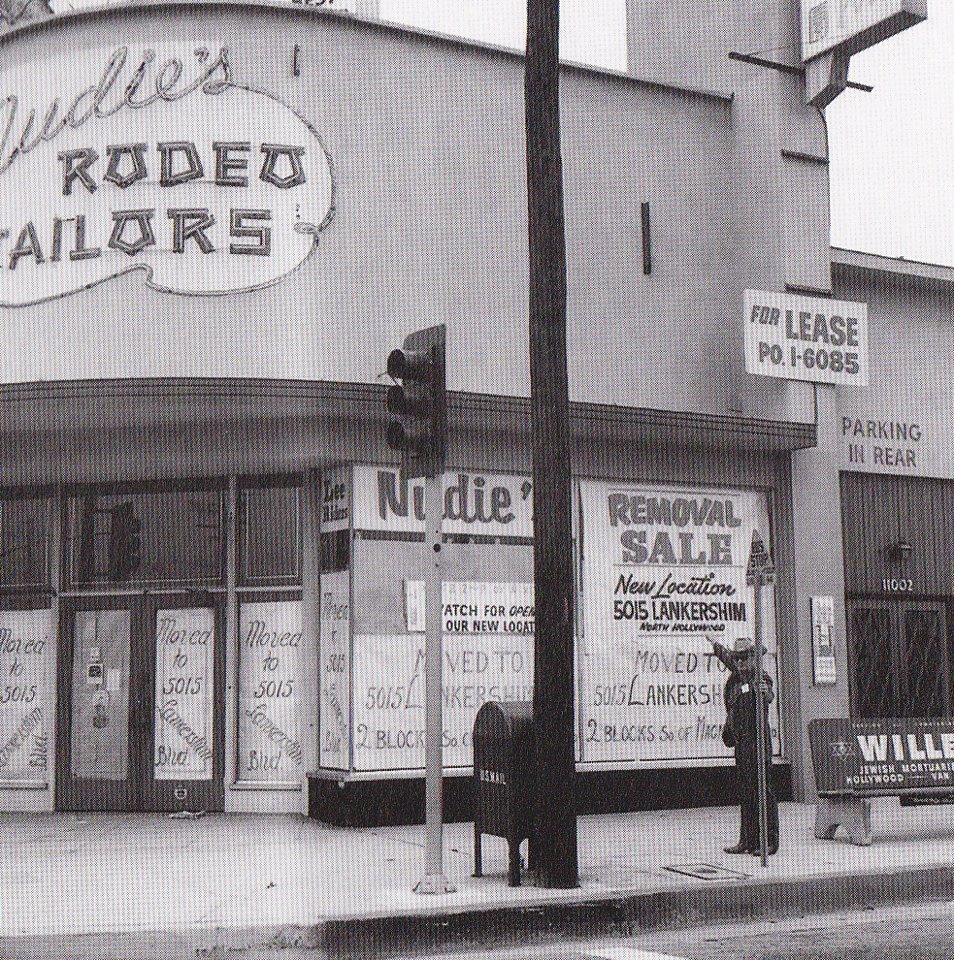

Tired of the rigors of New York, the family left for Hollywood, California in the early 1940s, and by 1947, they turned their g-string business into a full custom tailoring house. Nudie had it in his mind that he could make bedazzled “rhinestone cowboy” suits for sparkling superstars, but he needed the right machinery and clients. He persuaded a young, struggling country singer named Tex Williams to sell his quarter horse at auction and use the proceeds to buy him a chain stitch machine. In return, Nudie promised to make him a suit. The deal turned out better than he could have hoped. Williams ended up with a chart-topping cover of Merle Travis’ “Smoke! Smoke! Smoke!” in 1947 and started plugging Nudie over the radio. By the end of 1949, Nudie and his wife moved their garage business into their first store, located on the corner of Victory Blvd and Vineland Ave in North Hollywood. They went by the name Nudie’s Rodeo Tailors, or sometimes, more simply, Nudie’s of Hollywood.

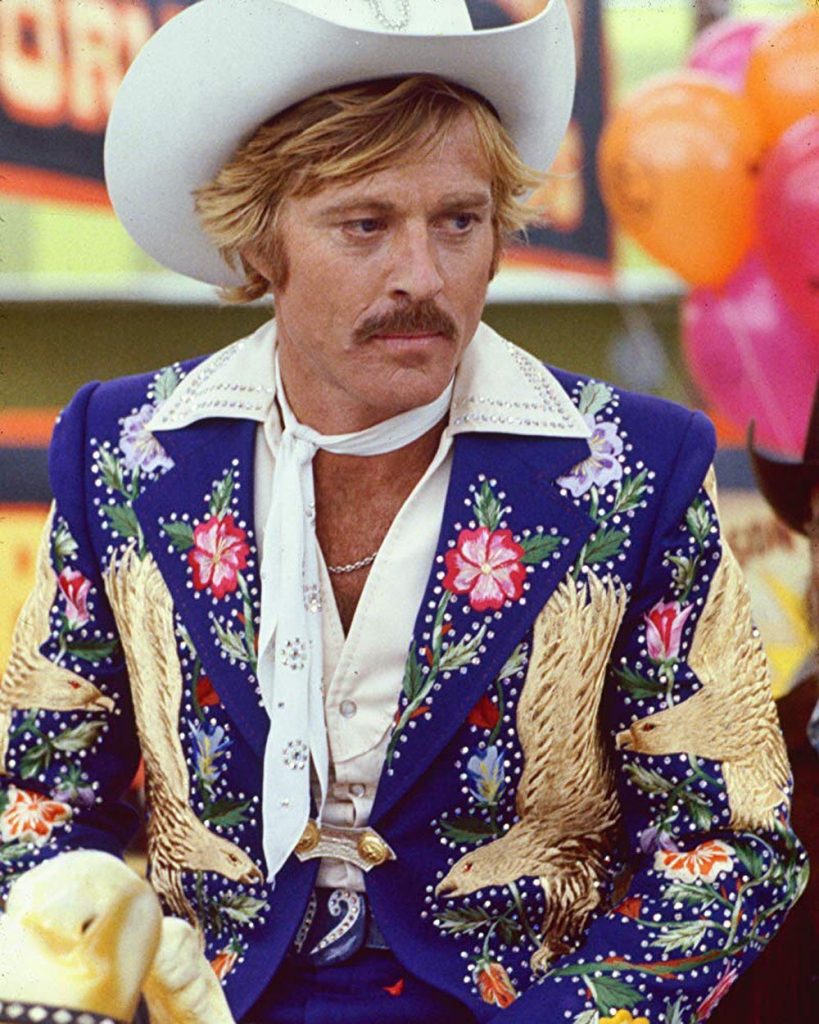

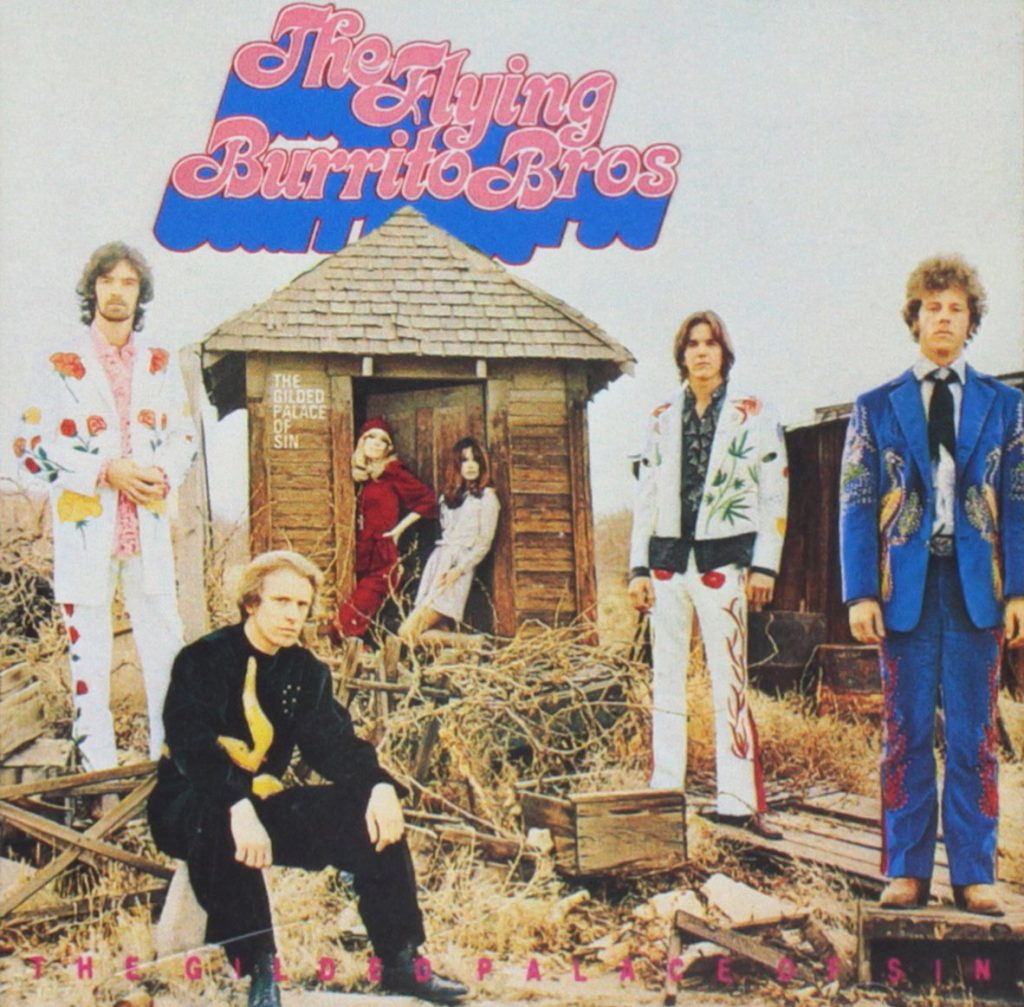

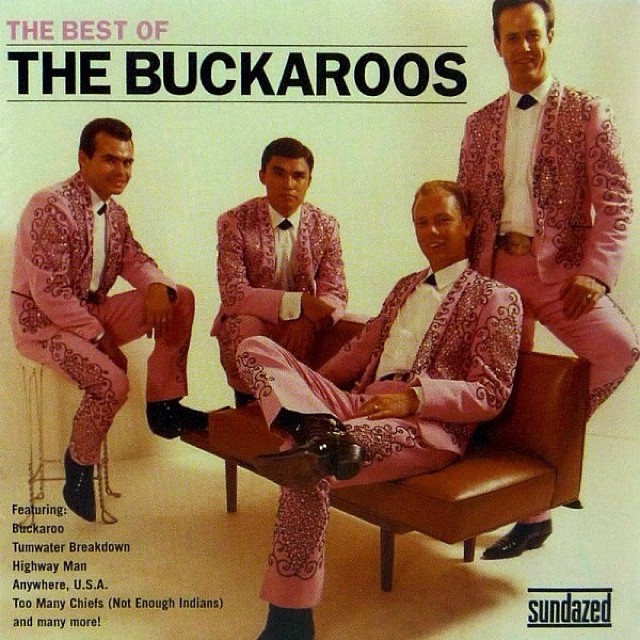

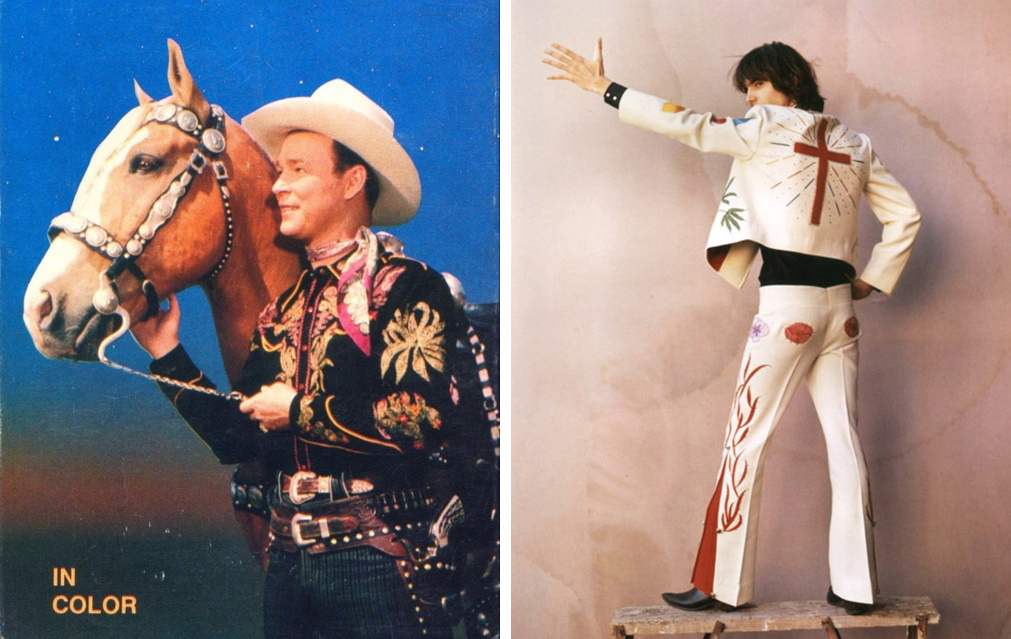

In those early days, Nudie mostly dressed country music stars, such as Hank Williams, Hank Snow, and Hank Thompson (lotta country singers named Hank). But when Gram Parsons commissioned a custom suit with embroideries referencing sex and drugs — motifs like naked women, marijuana plants, and the red poppy flower used to make heroin — rockstars and actors started getting into the style. Over the course of his career, Nudie dressed everyone from Bootsy Collins to ZZ Top, Jerry Garcia to Sly Stone, Bob Dylan to Liberace. The purple and gold, eagle-emblazoned suit Robert Redford wore in the 1971 film The Electric Horseman? That was by Nudie. So was the gold lamé suit that Elvis wore on the cover of his 50,000,000 Elvis Fans Can’t Be Wrong album. If lore is believed, Nudie sold that suit for $10,000 — and made a profit of $9,950 (nearly $100,000 in today’s dollars).

In the history of American dress, there has always been a dividing line between the tasteful and brash, high brow and low brow, classic and fashionable. Nudie’s suits were so lurid, they eluded this binary and created their own category. These suits didn’t just sing; they shouted, hollered, and walloped. When Nudie made his first suit for Roy Rogers — what would become the first of many — Rogers requested that the suit be so vivid, even the “kid in the nosebleed section can see me.” When Rogers died, he was buried in one of his Nudie suits.

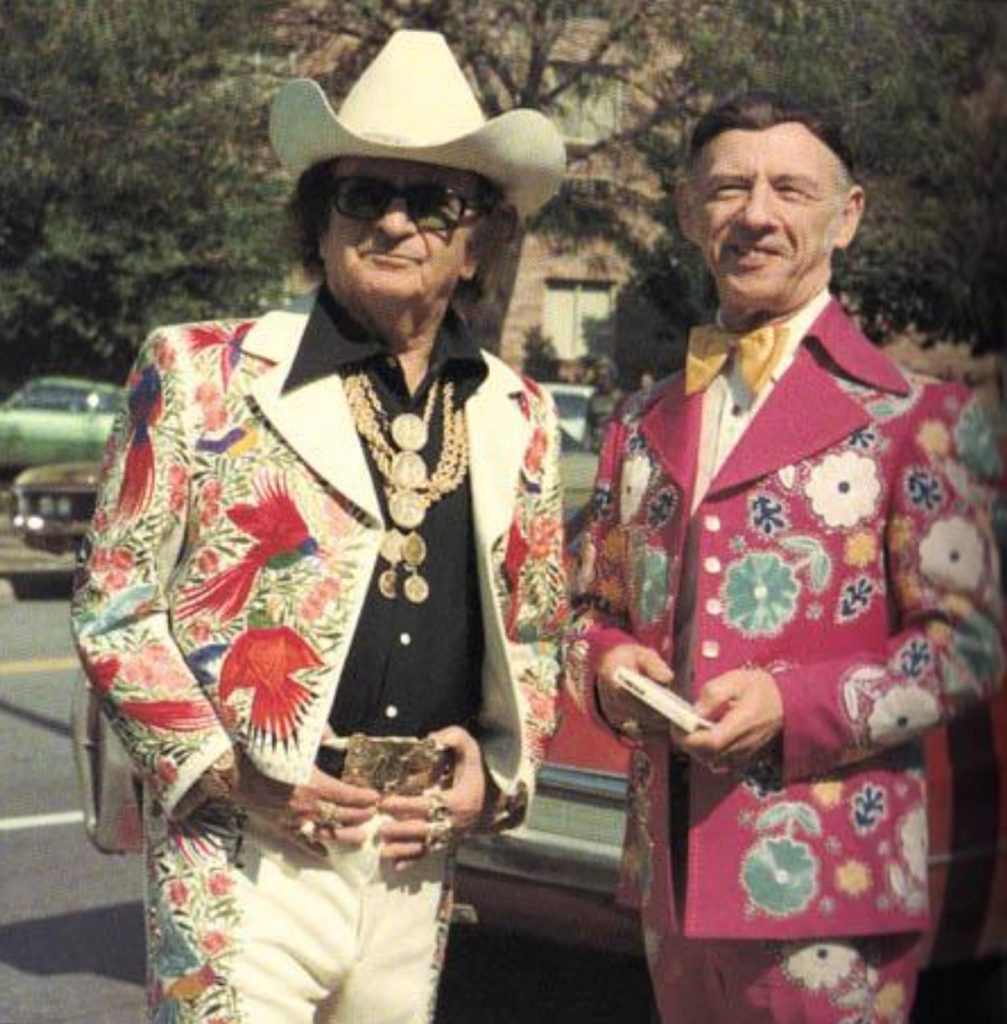

Nudie’s outlandish style extended to everything. He was his own proselytizer, wearing shimmering fringed suits, giant cowboy hats, oversized sunglasses, and multiple gold chains. He was a mandolin player of considerable skill and occasionally played for customers, claiming that the serenades encouraged them to stay longer (and, hopefully, buy something). Between 1950 and 1975, he also customized eighteen “Nudie Mobiles,” which were shiny Cadillac and Pontiac convertibles festooned with typical Nudie iconography — dashboards covered in silver dollars, pistols used as car handles, and giant steer horns functioning as hood ornaments. Even the car horns were customized to sound like braying mules.

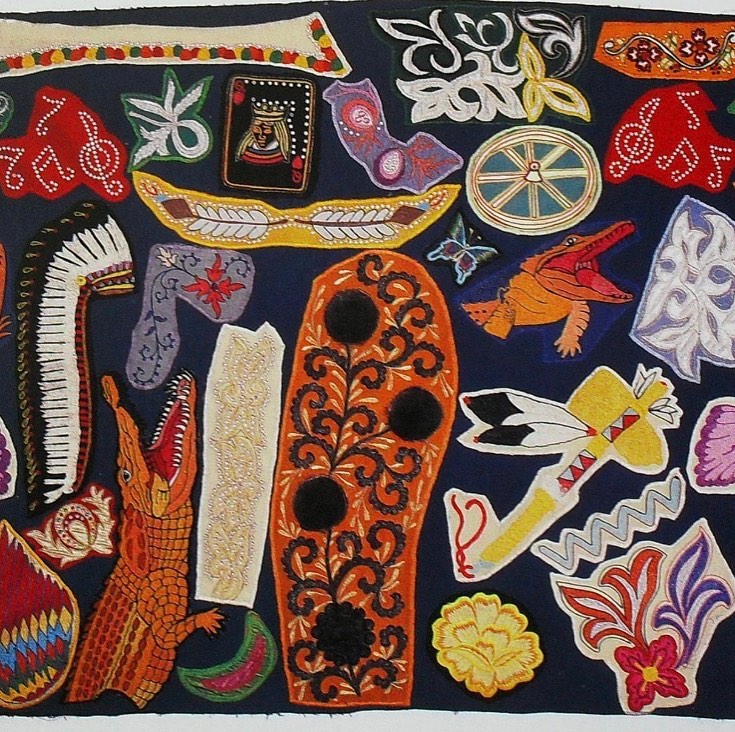

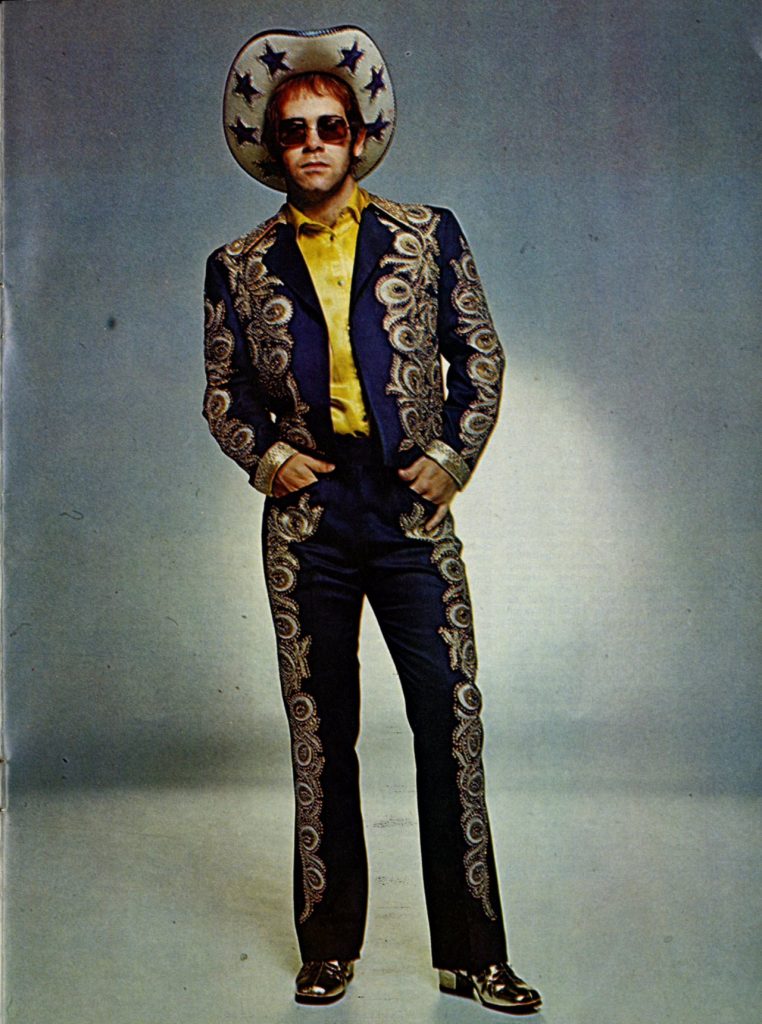

When Nudie died in May of 1984, he had a fully open casket so that people could see his mismatched boots, which over the course of his life, had become something of a style signature and a personal reminder of his modest background. It’s easy to think of this style as just a strange blip in the history of American fashion. Indeed, Nudie came up at a time when everyone went through a Westernwear phase — Cher, Elton John, and John Lennon among them — and they all stopped by this store that was wholly and uniquely Californian. But the style lives on to degrees that many don’t even recognize. To be sure, Westernwear is having a moment again, and tiny operations such as Fort Lonesome, Union Western, and RoseCut are making Nudie-styled suits for a new audience. The style can be seen on contemporary stars such as Post Malone, Lil Nas X, and Yeah Yeah Yeah’s Karen O. But you can also see his influence in today’s big-name luxury brands. Shortly after he was appointed as the new creative director of Gucci, Alessandro Michele made waves by releasing maximalist, metal-and-gem studded clothes with embroideries and appliques. The leather jacket pictured above, which is from Gucci’s 2016 collection, has echos of Nudie’s vision.

While researching for this post, I found myself questioning some of the stories behind Nudie’s life. Did his mother really tell him that America’s streets were “paved with gold?” Did a school teacher actually give a young Nudie a pair of mismatched boots? I imagine no one will ever know if these are facts or just stories spun by a brilliant salesman, but therein also lies some of the beauty. Nudie Cohn and his suits are quintessentially American in ways that go beyond kitschy style and Hollywood stars. He was a Ukranian immigrant who knew the heart of American style better than many Americans, a self-made man who invented himself using stories and clothes. Nudie landed in the United States at a time when New York City’s garment district was mostly staffed by Eastern European Jewish immigrants in search of a better life. Nudie was just one of many, although he arguably shined the brightest. Today, those seats are filled by immigrants from East Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean using garment factory jobs as a stepping stone, following the same path as those Eastern Europeans before them. It’s a continuing story about how immigrants shape American style, and our connections to the world.