Last year, shortly after it was established that wearing a facial covering can help slow the spread of COVID-19, some guys in my neighborhood started sporting bandanas. They wore them like bandits — neatly folded into a triangle, wrapped around the lower half of their face, and then tied at the back, like you’d imagine on a train robber in an old Western film. Inspired by the look, I started wearing a rolled bandana loosely tied around my neck. I had always dismissed the style as an affectation — something you see in the glossy pages of GQ or online street-style photos of guys hanging outside fashion shows. But shame didn’t deter me. I figured, if my fashion experiment failed, my surgical face mask would hide my identity.

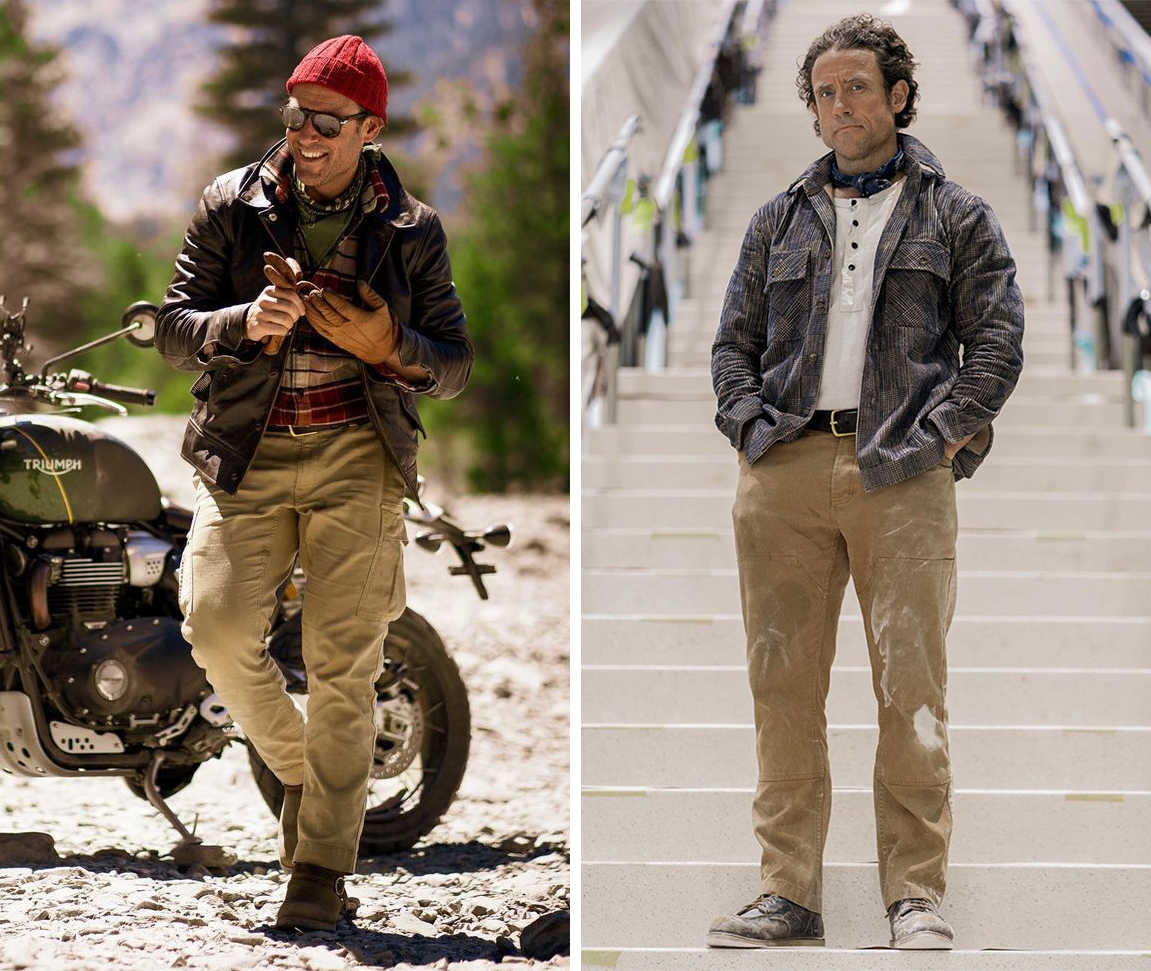

Since then, a bandana has become almost a daily accessory for me. Fear of looking out of place has mostly faded, much like my skepticism of hats after I purchased my Lock & Co Rambler. Having worn a bandana so often now, certain outfits don’t look right to me without one. With a plain white shirt and vintage Lee trucker jacket, a bandana can help fill the space created by the jacket’s open fronts and the shirt’s flat color. With a button-up flannel, it accentuates the neckline around an open collar. A bandana serves a similar function as menswear’s most controversial accessory — the ascot.

I’ve also started noticing an alarming number of “bandana guys” lately, not just in my physical neighborhood, but online. Bandanas worn as a superfluous accessory have shown up in Todd Snyder’s mailers, Aime Leon Dore’s lookbook, and The Armoury co-founder Alan See’s Instagram. The roving photographer behind Thousand Yard Style, Robert Spangle, sports them with field jackets, Western shirts, and bombers. Jamie Ferguson, the author of This Guy, recently wore one in a self-portrait. Jamie wears his bandana in a more “classic menswear” way — with a Baracuta parka, ochre Shetland, and some raw denim jeans. The blue bandana highlights his knitted cap and denim. When the points are tucked into the sweater, you hardly even notice it — the accessory simply adds a subtle and playful pattern.

Being such a simple accessory, bandanas have a rich tradition in nearly every culture. The first ones came out of India, where they were called bāndhnū or bāndhnā (Hindi for “tie-dying” or “to tie,” respectively). These words spring from the Sanskrit roots badhnāti and bandhana (“he ties” and “a bond”). When the East India Company imported them into Western Europe, they became popular with members of the merchant class. During the 18th century, wealthy Europeans who used snuff tobacco were embarrassed by the dark, dirty stains left behind on a white or solid-colored handkerchief when they blew their nose. Since Indian kerchiefs were typically darker and covered in lively patterns, they could blow their nose discretely. That’s how the Indian kerchief landed in Western Europe, and the Hindi term bāndhnā was anglicized to “bandana.”

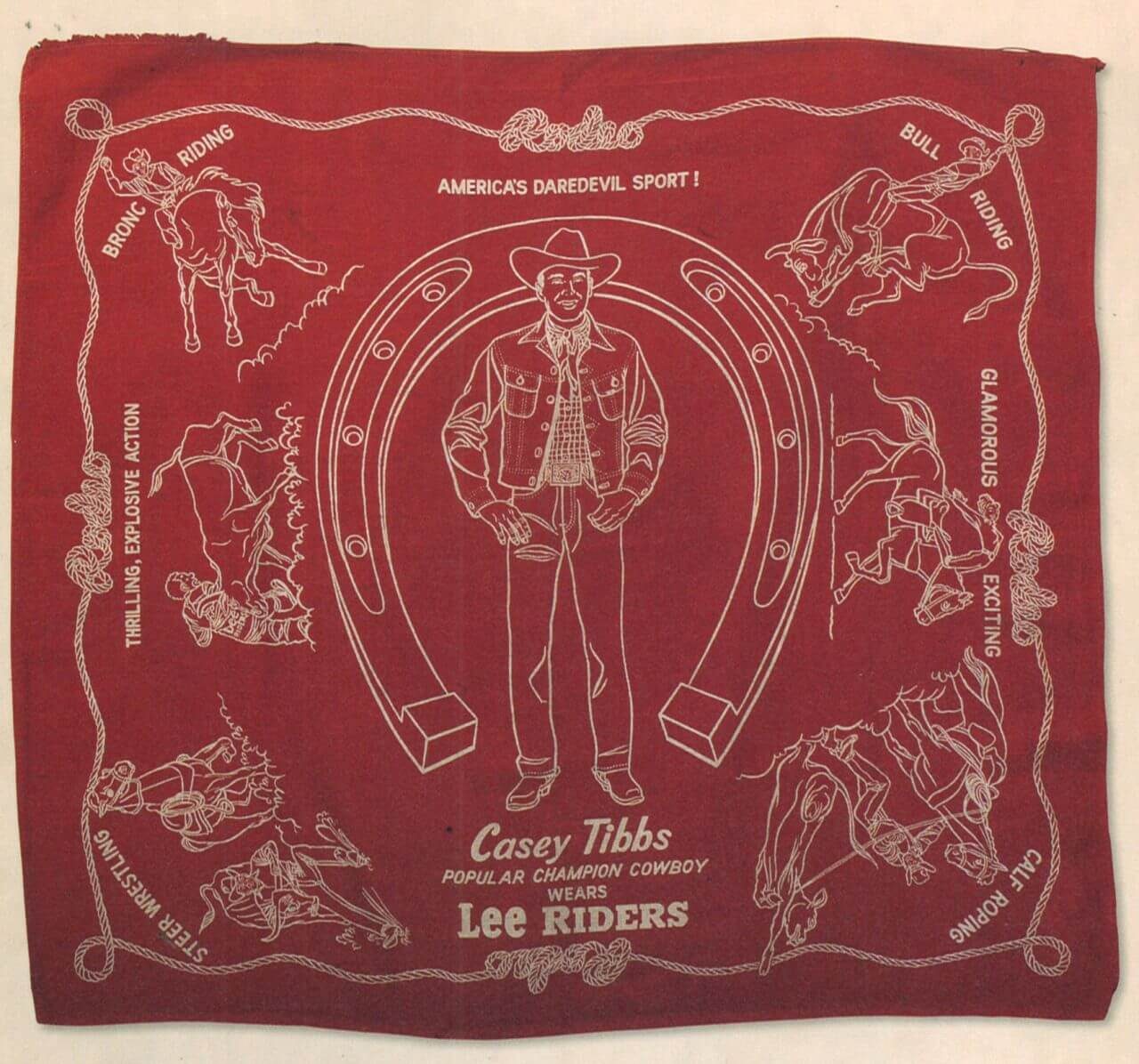

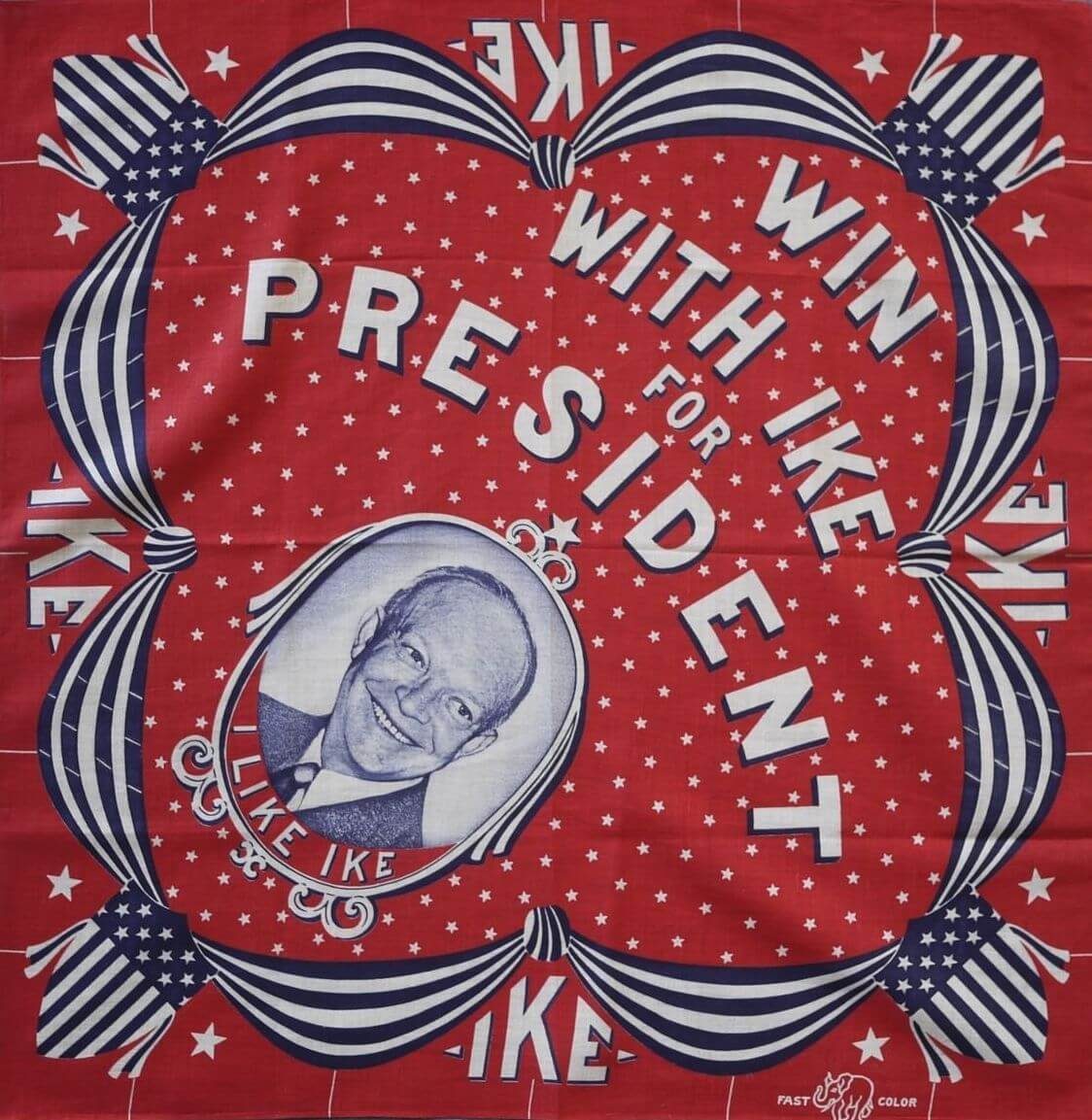

By the early 19th century, Europeans started producing their own bandanas. In Mullhouse, France, producers colored them with a dye made from a mixture of sheep dung, madder root, and olive oil. They then printed these bandanas with paisleys inspired by Kashmir shawls. In colonial America, guides used bandanas printed with maps. During the American Revolutionary War, patriots made block-printed bandanas with the image of George Washington astride on a horse, surrounded by cannons, flags, and the words: “George Washington, Esq. Foundator and Protector of America’s Liberty and Independency.” This was the first piece of political propaganda in the United States — and it was printed on a bandana.

Bandanas also have deep roots in workwear. In the mid-19th century, American cowboys wore what were known as “wild rags,” which were square sheets cut from old flour sacks (since cotton was scarce on the range, they had to make the most of what they had). They wore them for protection, as a bandana could keep the sun off your neck and dirt off your face. But in a pinch, a cowboy could also use a bandana to clean a firearm, hold a skillet, wipe his mouth, and rig a saddle. In his paper “Red Necks and Red Bandanas,” published in Western Folklore, historian Patrick Huber writes about how early 20th-century Appalachian coal miners used red bandanas to build multi-racial class solidarity and reclaim the epithet redneck.

One significant and meaningful way in which UMW [United Mine Workers of America] and other unions sought to cultivate this fragile multi-racial unionism among white, black, and immigrant minors was their redefinition of the epithet redneck and their adoption of the nickname, along with red handkerchiefs, as badges of union identity and class solidarity. […] The red bandana is one of the oldest symbols of the labor movement in both the United States and Europe. Such neckerchiefs have served as a form of protection for railroad men, miners, roughnecks, cowboys, loggers, and other American workingmen. For example, locomotive firemen who worked in the cabs near coal-fueled steam engines often wore such handkerchiefs in order to keep red-hot cinders from falling into their shirts. Coal miners likewise often wore kerchiefs for the purpose of keeping the gritty coal dust off their necks, from falling down their workshirts, and out of their noses and mouths.

But for union miners, the red handkerchief transcended its mere utilitarian purposes to become an emblem of union identity that elevated class and occupational grievances over racial and ethnic divisions. Union miners cleverly adopted the red bandana, a preexisting symbol of their work, to unite members of various races and ethnicities. During the 1910s and 1920s, a period of intense union organizing and labor strife in the northern and central Appalachian coalfields, striking native-born and immigrant union members occasionally tied red handkerchiefs around their necks or arms so that fellow union men from nearby mines could readily identify them. In fact, the UMW sometimes even distributed these handkerchiefs to miners during strikes. […] As a result, the epithet redneck began to assume more inflammatory connotations, including “anarchist,” “Bolshevik,” and “Communist.”

Peter Zottolo in San Francisco started wearing bandanas last year in response to the mask mandate. Although he had some bandanas in his drawer, he decided to upgrade his stash by adding some colorful bandanas from Canoe Club. These bandanas were made in collaboration with some StyleForum members, who contributed to the “For Ever” design. “It ticks all the boxes for me,” Peter says. “It’s a unique take on a classic style, it’s affordable, and best of all, it’s discharge dyed. This method of making bandanas used to be more common, but it’s somewhat rarer nowadays. The great thing about it is that the fabric fades like your favorite pair of jeans. As you wash and wear it, the color slowly leaches from the bleached cotton fiber, making the design appear softer and more muted than if the design was printed.”

Peter wears bandanas with all types of casual outfits. He tucks them under chambray shirts when he wears tweed sport coats and denim. While vacationing in Istanbul with his wife a few years ago, Peter sported a navy Universal Works bandana with an 18 East popover, featherweight Eidos trousers, and some woven leather sandals that he scored while in Italy. He also wears them with workwear ensembles — heavy leather jackets with cargo pants, or with corduroy overshirts, henleys, and double-knee pants when he’s on the worksite. “If I’m not wearing a bandana on my face, I simply twist it, tie it like a tie, and wear it loosely,” he says.

James in Brooklyn started wearing bandanas recently because of his partner, Liz. “We were sitting in Brooklyn Bridge Park, drinking orange Italian sodas on an unseasonably sunny day,” he says. “Liz noticed that my pale Irish skin had become ruddied by the sun, and promptly dressed me in her felt hat and bandana. I was soon affecting that I was Walt Whitman. I enjoyed the pretense so much that I went out and acquired a rabbit felt hat (from Cottle) and two Kapital bandanas of my own.”

“My interest in bandanas overlaps with an expanded interest in Amekaji and Japanese repro-wear, generally workwear and militaria, with some western motifs,” James elaborates. “But I’m not that discerning. I’m just as likely to wear a bandana with a leather biker jacket as I am with a Scottish cashmere sweater. I generally like to tuck the bandana points under my shirt or sweater collar à la Alessandro Squarzi (although my partner is pro exposed tips). I view bandanas as both the working person’s cravat and a miniature scarf: they are both flourish and pragmatic protection against the elements.”

Dan Roan, the Philadelphia-based blogger behind A Fine Tooth Comb, finds that bandanas can push an outfit towards more “artsy” or “rugged” directions. “Picture Pablo Picasso at home in a drapey shirt and some flowy pants, wearing a bandana that’s been lazily tied around his neck,” he says. “In a more rugged outfit, a bandana can be something Brando would have worn around his neck in The Wild One.” Dan mostly wears J. Crew’s Wallace & Barnes bandanas with workwear and workwear-adjacent outfits, such as ones involving French chore coats or a Fine Creek Leather cafe racer. A bandana tied with the points hanging down at the front of his neck gives these outfits a bit of visual interest and direction.

Although he’s pro-bandana, Dan recognizes there’s a risk here of looking affected. “Things that have a potential for looking affected or dandy tend to be superfluous: jewelry, hats on most days, and bandanas. If you wear these items, you have to be OK with that potential, to a degree. For that reason, however, my most worn bandanas tend to be the simplest ones and in the most neutral tones. A bandana in a complementary color can be a great way to add a touch of contrast to an outfit that otherwise might feel a little plain. I’m still figuring it out, though. Half the time, I end up tying one and taking it right off. Things that aren’t particularly mainstream require a bit of playing around — that’s part of what makes style fun.”

If you’re looking to experiment with bandanas, I find they go most naturally with workwear (evidenced by many of the outfits in this post). You can find bandanas almost anywhere nowadays — from cheap $3 Hav-a-Hanks at Tractor Supply to $430 Khadi bandanas from Visvim (lol). I prefer things in the middle — something that’s a little more interesting than the plain, two-tone bandanas in primary colors, but also doesn’t feel like a precious designer piece.

My favorites are from Kapital. Everything about their bandanas is perfect and seemingly obsessed over by vintage aficionados. There’s a subtle selvedge stripe on one side of every bandana. The patterns always look good when rolled (not too plain, like simple two-tone bandanas, and are often inspired by classic vintage pieces, as Canoe Club recently outlined in this post). Best of all, they come in just the right size and weight. Some bandanas are printed on heavier cotton and thus look bulky around the neck. But these are just thin enough to look natural when worn. Since they rely on a lot of black, blue, and olive, they naturally complement colors dominant in workwear. The downside is that they’re relatively expensive at $40 to $60 — but let me tell you, they are genuinely great. Kapital’s bandanas are available at Glasswing, Canoe Club, Standard & Strange, Stag Provisions, Cotton Sheep, and Independence. I personally wear the olive smiley face, blue patchwork, and black concho designs the most.

More affordably, you can pick up a cotton bandana from Ginew, United By Blue, Wallace & Barnes, Human Made, Blue Blue Japan, Universal Works, Todd Snyder, Sendero, Kiriko, Fortela, 3sixteen, and Bandits. I really like the dusty colors in Reliquary’s vintage stash. Eco Raw Studio makes beautifully designed, uber-soft bandanas from raw silk. Since these fabrics are naturally dyed using pure plant extracts, the colors naturally fade over time. I love the slubby texture of their bandanas, but they stand out more since they are more brightly colored. There are also countless independent bandana sellers on Etsy, and you can search for vintage bandanas from the coveted Elephant Brand.

If you’re still a bandana skeptic try this: the most discrete way to wear one is by tucking it underneath a turtleneck. Depending on the fabric of your knitwear, a turtleneck can sometimes be itchy against bare skin. The perfect solution is to wear a bandana underneath, ideally something made from silk or cotton. The bandana will mostly stay hidden, but it will peek out at different times and angles, depending on how you wear your sweater. As you get used to the accessory, you may also find yourself wearing it without the high collar.