This past week, seven states issued mandates requiring residents to cover their faces when they visit essential businesses or use public transportation. Those states include Connecticut, Hawaii, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island. In my home state of California, several Bay Area counties are now imposing the same measure. These mandates were issued after researchers found that a significant portion of individuals with COVID-19 lack symptoms (“asymptomatic”). And that those who eventually develop symptoms (“pre-symptomatic”) can still transmit the virus to others before showing signs of sickness. By getting more people to wear masks, the Center for Disease Control is hoping it can help slow the spread of this virus and thus lower the number of deaths.

If you’re scrambling trying to figure out what’s the best facial covering, you’re not alone. While researching for this article, I found conflicting and incomplete information, often from very reputable and established sources. However, almost all officials agree on three things. First, wearing some facial covering is better than not wearing one at all. Second, certain masks are better than others, and their efficiency hinges on their filtration system. Third, it’s important to have a mask that fits your face well. Let’s cover some of the basic options.

An N95 with an exhalation valve

N95

By now, you’ve probably heard of the N95 mask, which is the Gold Standard. The name refers to how the masks can block 95% of tiny particles (those measuring 0.3 microns, which are the hardest to capture). The reason why there’s a shortage is partly that there’s a massive surge in demand among medical professionals working on the frontlines. It’s also because these masks rely on a unique material known as meltblown.

Nearly all the fabrics you find on the market are made from yarns, which are spun and then woven. Meltblown is distinctive in that it’s a non-woven fabric, which means a machine spits out a material sort of like cotton candy. This material is much more effective at filtration, while still allowing you to breathe. However, it’s challenging to build machines that produce melt-blown. With the considerable surge demand, suppliers have been struggling to keep up.

A few weeks ago, I talked to a senior executive in the menswear industry who’s currently trying to source meltblown, as well as find a way for hospitals to more safely disinfect N95 masks without reducing their efficiency. One of the reasons why N95s are so effective is because the material has a static electric charge, but that charge becomes less effective when it’s exposed to humidity. As he tells me, the goal for many hospitals right now is trying to figure out a way to safely reuse the N95 masks they already have on hand.

Some N95 masks are built with a one-way valve, which is designed to ease exhalation and decrease humidity, heat, and moisture inside (such as the mask pictured above). These are common in Northern California as they’ve been used to fight wildfires. However, the same valve that allows you to breathe easier also allows large respiratory droplets into the air when you breathe out (and especially when you sneeze or cough). For that reason, they’re less effective than the standard N95 mask. We recommend leaving the proper N95 masks to medical professionals, who need them the most, and looking for some other solution than N95 respirators.

Medical Mask

Medical masks, which are also known as procedure masks, are the kind of masks you’d imagine when you think of a doctor doing into surgery. They’re mostly designed to protect against large splashes of water or sprays in medical facilities.

These masks are typically made from three layers of a non-woven synthetic material, which makes them more effective than your standard piece of woven cotton fabric. However, since they don’t fit as snugly against your face like a proper fitting N95, they’re also not as protective. When you sneeze, tiny droplets can escape from the top or sides. You can reduce your risk by pressing down on the metal nose piece, so it conforms to your nose. And try to wear this in a way so that it fits close against your face. The New York Times has a useful guide on how to wear masks properly. Assuming you have a good, proper fit, The New York Times estimates that medical masks filtrate about 60 to 80 percent of tiny particles.

Homemade Masks

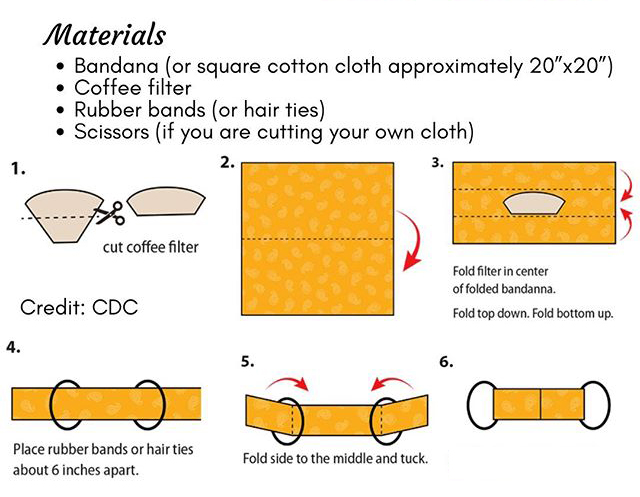

You can also make your own mask at home. There are dozens of guides on how to construct these using everything from shop towels to a simple cotton bandana.

Remember, the goal is to filter out tiny particles while still allowing yourself to breathe comfortably. Try to find materials that help you achieve this. Find a densely woven cloth, made from a thicker material, and then fold it over on top of itself to create multiple layers of protection. You can sandwich something in-between, such as a coffee filter (a non-woven that’s still breathable) to help catch more particles. Just be careful with other kinds of filters, as they may contain chemicals, fiberglass, or small fibers that you don’t necessarily want to be breathing in. Air filters can be a bad idea for this reason.

The New York Times has a guide on how you can make your own mask at home, as well as choose a good material. To see if a material is protective, hold it up to the light and see how much light comes through (the less light, the better). “Dr. Wang’s group also found that when certain common fabrics were used, two layers offered far less protection than four layers,” writes Tara Parker-Pope. “A 600 thread count pillowcase captured just 22 percent of particles when doubled, but four layers captured nearly 60 percent. A thick woolen yarn scarf filtered 21 percent of particles in two layers, and 48.8 percent in four layers. A 100 percent cotton bandanna did the worst, capturing only 18.2 percent when doubled, and just 19.5 percent in four layers.”

“If you are lucky enough to know a quilter, ask them to make you a mask,” she continued. “Tests performed at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine in Winston-Salem, N.C., showed good results for homemade masks using quilting fabric. Dr. Segal, of Wake Forest Baptist Health, who led the study, noted that quilters tend to use high-quality, high-thread-count cotton. The best homemade masks in his study were as good as surgical masks or slightly better, testing in the range of 70 to 79 percent filtration. Homemade masks that used flimsier fabric tested as low as 1 percent filtration, Dr. Segal said. The best-performing designs were a mask constructed of two layers of high-quality, heavyweight ‘quilter’s cotton,’ a two-layer mask made with thick batik fabric, and a double-layer mask with an inner layer of flannel and outer layer of cotton.”

First photo: General Quarters’ mask; Gallery: a selection of Rowing Blazers’ masks, dropping April 23rd on their website

Non-Medical Masks

In the last few weeks, as more factories are retooling their machines to make masks, there have been more options coming onto the market. It’s difficult to compare their effectiveness because a lot depends on how these masks are made. With a loosely woven fabric, you’re going to get less filtration. The same is true if the design isn’t made to fit tightly around your face.

When shopping for a mask, try to look for two things. First, if it’s built like a medical mask, such that you have pleated, rectangular panels, ideally it should have a metal nose bridge at the top so you can mold this to your face (a feature that’s difficult to find, although Tony Shirtmakers and Kabazz & Kelly have some). Secondly, woven materials, in this case, are often better than knitted materials. Wovens are like your dress shirts — they don’t stretch. Knitted fabrics are like your t-shirts — they do stretch. Depending on how the knitted fabric is made, sometimes the holes between the yarns can open up when you stretch the material. You can find woven masks from General Quarters (pictured above), Kamakura, Tony Shirtmakers, Monsivais, Beau Ties, Magill, Lone Wolf, Ball & Buck, Apolis, Mountain & Sackett, Kabbaz & Kelly, American Trench, Face Mask Aid, and any number of Etsy sellers. Get something made from multiple layers of material, as it’ll offer more filtration.

Our sponsor Rowing Blazers is also making masks this week from their leftover cotton shirtings, which include madras, corduroy, oxford cloth, and various rugby and croquet stripes. These are made in New York City and will be available on Rowing Blazers’ website starting this Thursday, April 23rd. Company founder Jack Carlson tells us that he’s donating a portion of the company’s mask inventory to workers at NYC’s Food Bank. You can see a selection of them above.

Further reading: The New York Times has been doing some great reporting on this. See their articles on which mask you should wear, how to wear a mask properly, what the best materials are for making a mask, and how to sew your own. They also have a lot of this information neatly summed up in a full user’s guide to face masks.