Everyone has heard the phrase “no white after Labor Day.” The idea comes from a time when Americans used to bracket summer with Memorial Day on one end, and Labor Day on the other. But how did the actual rule come about? Time Magazine has a nice piece that explores some of the more popular theories:

One common explanation is practical. For centuries, wearing white in the summer was simply a way to stay cool — like changing your dinner menu or putting slipcovers on the furniture. “Not only was there no air-conditioning, but people did not go around in T shirts and halter tops. They wore what we would now consider fairly formal clothes,” says Judith Martin, better known as etiquette columnist Miss Manners. “And white is of a lighter weight.”

But beating the heat became fashionable in the early to mid-20th century, says Charlie Scheips, author of American Fashion. “All the magazines and tastemakers were centered in big cities, usually in northern climates that had seasons,” he notes. In the hot summer months, white clothing kept New York fashion editors cool. But facing, say, heavy fall rain, they might not have been inclined to risk sullying white ensembles with mud — and that sensibility was reflected in the glossy pages of Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, which set the tone for the country.

This is all sound logic, to be sure — but that’s exactly why it may be wrong. “Very rarely is there actually a functional reason for a fashion rule,” notes Valerie Steele, director of the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology. True enough: it’s hard to think of a workaday downside to pairing your black shoes with a brown belt.

Instead, other historians speculate, the origin of the no-white-after–Labor Day rule may be symbolic. In the early 20th century, white was the uniform of choice for Americans well-to-do enough to decamp from their city digs to warmer climes for months at a time: light summer clothing provided a pleasing contrast to drabber urban life. “If you look at any photograph of any city in America in the 1930s, you’ll see people in dark clothes,” says Scheips, many scurrying to their jobs. By contrast, he adds, the white linen suits and Panama hats at snooty resorts were “a look of leisure.”

[…]

By the 1950s, as the middle class expanded, the custom had calcified into a hard-and-fast rule. Along with a slew of commands about salad plates and fish forks, the no-whites dictum provided old-money élites with a bulwark against the upwardly mobile. But such mores were propagated by aspirants too: those savvy enough to learn all the rules increased their odds of earning a ticket into polite society. “It [was] insiders trying to keep other people out,” says Steele, “and outsiders trying to climb in by proving they know the rules.”

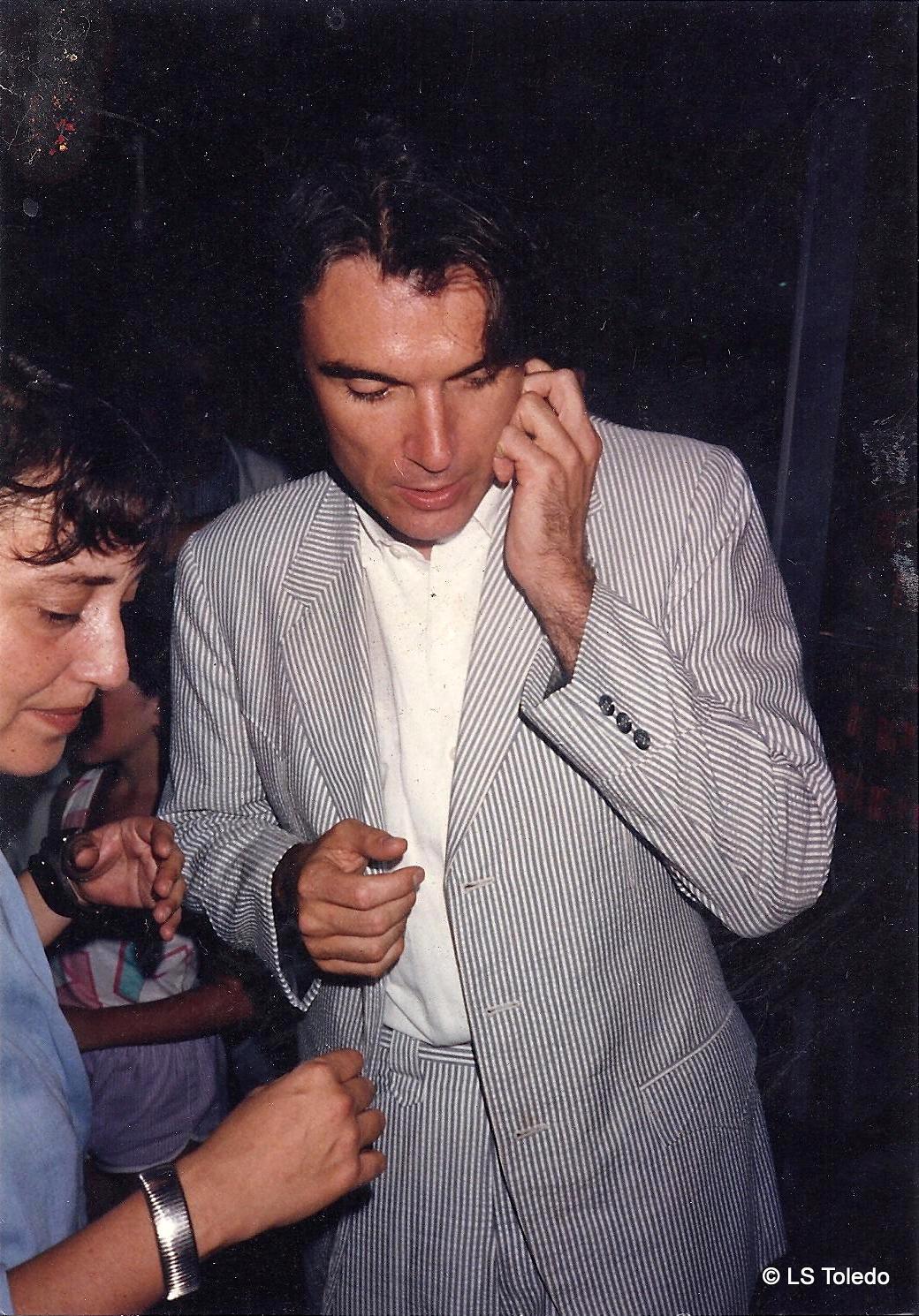

(pictured above: David Byrne of the Talking Heads in a seersucker suit)