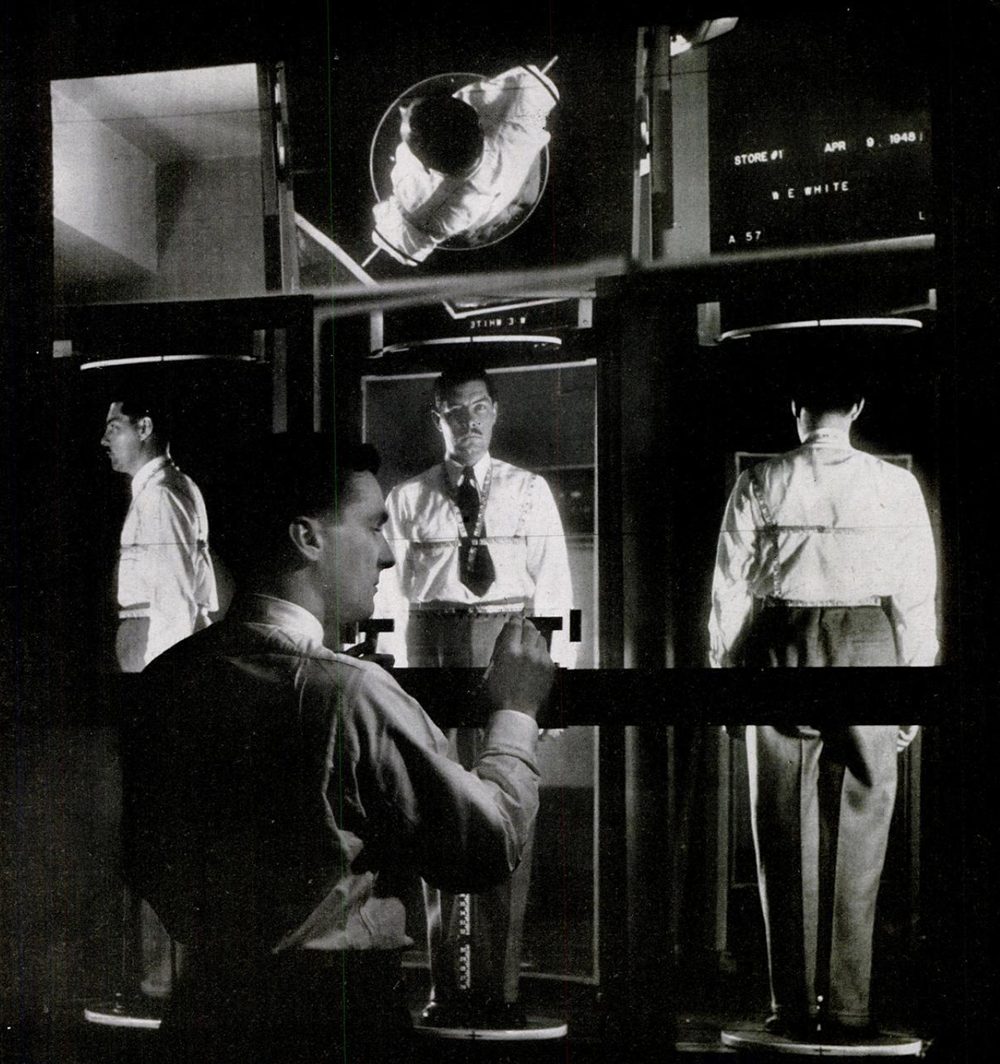

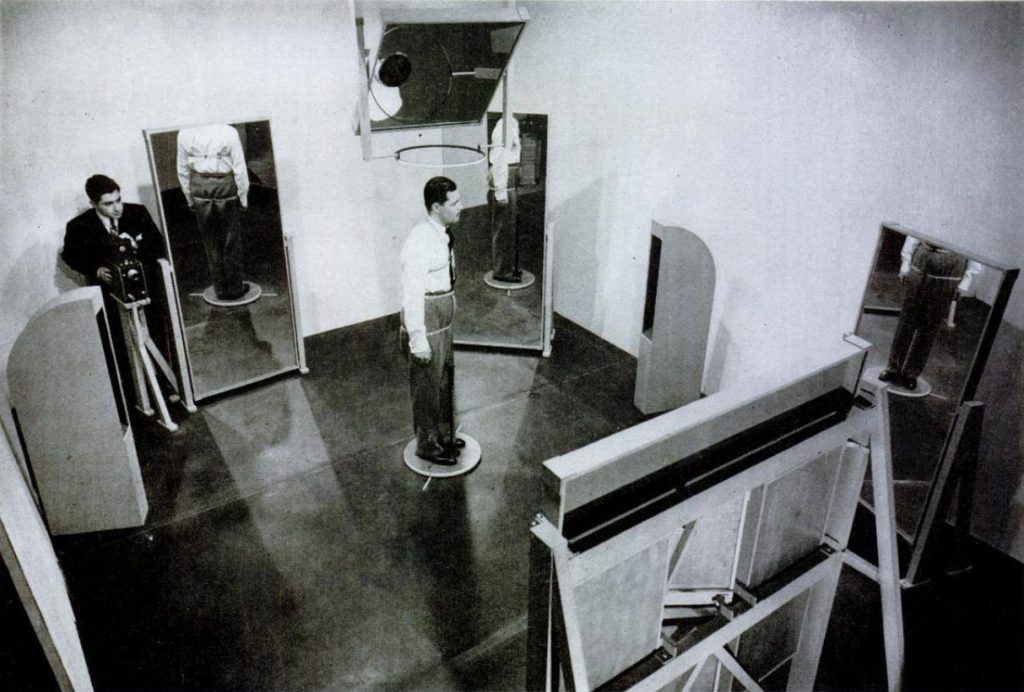

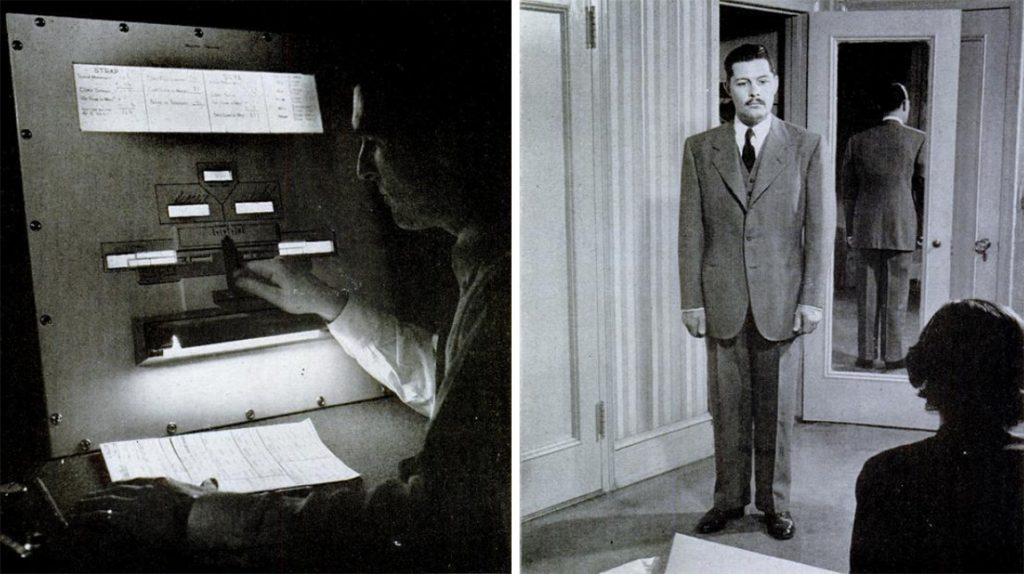

In June 1948, Life Magazine published a short article on a new-fangled fitting system called the Photo-Metric, which promised to deliver better custom clothes for men. The system worked in four steps. First, a customer would stand on a pedestal in the middle of a room while strapped into a harness made of measuring tape. Surrounded by nine full-length mirrors, which were widely spaced apart, his image was then projected onto a big screen at half scale. A photographer would then photograph that projection, after which the customer was allowed to leave.

Once the film was developed, a technician would use a series of scientific gauges and geometric calculations to derive not only the person’s ordinary bodily measurements, but also the slope of their shoulders and the spatial relations between their chest and waist. These numbers were then used to create a custom pattern, off which a custom suit would be cut. Henry Booth, the veteran textile distributor who invited the method, claimed his photographically tailored suits fit better than any other suit on the market. The cost for such a garment? Somewhere between $85 and $135 in 1948 (or roughly $915 and $1,450 in today’s dollars). Life Magazine at the time predicted that the Photo-Metric could revolutionize the tailoring industry. “In time, it may not only reduce the cost of a custom suit but may even replace the ready-made suit of medium price since it eliminates the big inventories and alteration expenses which now burden the ready-made suit retailer.”

You can probably guess what happened to the Photo-Metric. Walk down the hall to the long fitting room at Anderson & Sheppard, or any of the bespoke tailoring houses located in and around Savile Row, and you’ll be measured in much the same way that clients have been measured since tailors set up shop in Mayfair in the late 1800s. Today, even the world’s best bespoke tailors use little more than the $2 measuring tape. The Photo-Metric mostly survives as a curious article in a 1948 issue of Life Magazine.

Robert Jeffery Diduch, the Vice President of Technical Design at Hickey Freeman and part-time pattern maker at Samuelsohn, thinks that’s all about to change. “Much like how the move to a subdivision of labor changed the industry in the late 1800s, and the fusible changed it again in the 1950s, I think we’re on the cusp of another shift,” says Diduch.

Before moving on, we should say something about how custom clothes are made. Broadly speaking, custom clothing is broken into two types: bespoke and made-to-measure. Bespoke means that a custom pattern has been drafted for you by hand — either sketched out using a series of measurements or adjusted from a block pattern (the trade term for a template). A tailor then hones and perfects that garment through a series of fittings.

Made-to-measure, on the other hand, is typically made with a pattern that has been drafted using a computer-aided design tool (or CAD program). Being digitally manipulated means there’s less flexibility in terms of adjustments. And since made-to-measure is typically done with one fitting, rather than three, a tailor doesn’t have as many opportunities to refine that garment. This can be fine if your body is within a certain range of the block pattern, but once you start to deviate too much, you can wind up with a mess.

Custom clothiers promise to deliver better-fitting clothes than what you can find off-the-rack. But in reality, the process can be complicated, and there are many points where something can go wrong. For one, tailors require good measurements, and if they’re working with a customer remotely, that may mean they need the customer to measure themselves. This can be fine for simple garments such as shirts, but more difficult when you’re trying to make custom suits and sport coats. Secondly, a company needs someone who can turn those measurements into a suit (what Diduch calls “the secret sauce”). Thirdly, there’s the quality of the fitting process. In bespoke, a cutter is usually present at your fittings, which closes the gap between the fitting and pattern drafting process. With made-to-measure, the person cutting your pattern may be located far away in an overseas factory, which means they never see you. Consequently, they rely on the fitter to accurately communicate what needs to be done.

As the made-to-measure market has grown and evolved, companies have tried to overcome these challenges by using different solutions. Some hold trunk shows in different cities, so they can measure you in person. Others train local salespeople who can visit you in your home or office. By and large, the most reliable method relies on sample garments, whereby a salesperson will fit you in the best fitting off-the-rack option so that he or she can see what needs to be adjusted. In this way, the sample garment almost serves as an additional fitting — you get to see how the block pattern looks on you. However, since it’s difficult to lug around a full-size run of suits everywhere, this solution isn’t easily portable.

Occipital’s 3D scanner can be attached to anything from iPads to robots, and it only costs $400

In the last few years, companies have come up with more technologically advanced versions of the Photo-Metric. There are now handheld scanning devices, including proprietary attachable scanners, as well as apps that you can download onto your iPhone. Some companies have even developed bodymetrics pods, which combine body-scanning with virtual-reality technologies. These solutions promise to get companies over the first hurdle of extracting accurate measurements (at least in theory). “When you’re taking physical measurements, you are looking for certain physical landmarks,” Diduch explains. “You’re using the seventh cervical vertebra or acromion process in the shoulder, for example. But after that, it’s all about how you interpret those measurements.”

Recently, Diduch teamed up with Tailored, an Amsterdam-based company that specializes in made-to-measure clothing. They’re working on a new system that tries to solve the second part of this problem: how to draft bespoke-level patterns from scratch, but still using a made-to-measure system. Theoretically, this should allow them to create better fitting garments since they’re not hemmed in by blocks. “We took the traditional drafting system and modernized it, and applied what I know about truing, which is the process of perfecting patterns for factory production,” says Diduch. “Whereas drafting systems tend to be done using calculations based on a certain proportion of the chest and height, ours relies on a complicated ‘if/ then’ algorithm. In other words, if the difference between the stomach and chest is less than seven inches, then you’re doing one set of calculations. If it’s more than seven inches, then you’re doing another set of calculations. It’s all conditional, which allows us to create a custom pattern from scratch.” Tailored also uses specialized algorithms for fabrics — a pattern cut for Harris tweed needs more room in certain places, whereas linen requires the tailor to open up the back of the armhole.

At the moment, Tailored is looking for people who can break their system. “The more data we have, the better,” he says. “If you’re a typical skinny European, then we can make you a custom garment straight to finish. But we’re looking for those crooked figures, the bodybuilders, and those outliers who have trouble finding clothes off-the-rack or even made-to-measure. Our system requires a robust number of measurements.”

Photos of Tailored’s basted try-on, which is the first draft of a custom pattern

To get that data, Tailored is offering a special deal whereby you can get a made-to-measure suit for the highly discounted price of a few hundred Euros. The catch? It has to be a suit, and you can only choose certain fabrics (this allows them to more easily compare how the garments turned out across a range of people). You also have to be present for the fitting and delivery, as they need to see how the garment looks on you. Since the company is based in Amsterdam, they can most easily see customers at their headquarters. However, they’re also taking names of people in other cities who are interested in this promotion. If there are enough people in a particular location, they’ll make a trip. Tailored will cover European cities. In the future, Luxury Men’s Apparel Group — which is the parent company for Samuelsohn, Hickey Freeman, Culturata, and other labels — will make this available in the United States.

Readers who are interested can email peter@tailoredby.eu. The company is only offering suits at the moment, not sport coats. However, readers who primarily wear odd jackets can use this promotion to hone and perfect their pattern for a future order. Customers should also know they’re signing up to be part of a data-gathering process. Tailored isn’t promising that the suits will turn out perfectly, but they should be wearable.

As for how made-to-measure will change in the future, Diduch believes the tailoring industry is on the brink of a significant shift. Developments in true-depth sensors on cell phones will make it easier for sales associates to extract accurate measurements, and the portability of those devices will make bodymetric pods obsolete. “In the future, you may walk into a place such as Nordstrom and get scanned by a sales associate,” says Diduch. “That scan can then be sent to a technician in a remote location, who will use it to create a 3D avatar of you. A tailor will then use that avatar to create a custom garment. Since you’re being fitted digitally, a tailor can see how the garment fits and drapes on you, and then make adjustments on the fly without needing you to be present. This technology already exists, but it’s laborious to clean up those scans so they can work for a 3D avatar. As the cleanup process becomes faster, it’ll be more affordable.”