Jonathan Wertheim is the one-man operation behind the popular Instagram account Berkeley_Breathes. Part anthropologist and part fashion curator, Wertheim spends his days combing through yearbooks, both from prep schools and colleges, and curates a selection of photos on Instagram to give viewers a look at what he uneasily describes as “Ivy” style. Yes, there are plenty of Shetland sweaters and 3-2 rolls, but he also shows how campus fashion shifted, and how clothes were used more as a form of self-expression, rather than the codified uniform described online today. Through his archive, digging skills, and eye for detail, Wertheim documents generations of popular collegiate fashion in America. Wertheim shared some of his favorite photos with us and chatted about “Ivy” style: how the past can influence modern style, the association between “Ivy” and far-right politics, and why this style is still for everyone.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Charles McFarlane: How did you get into “Ivy” style?

Jonathan Wertheim: I’ve been interested in clothing for a long time. At some point, I wanted to know more about this specific style. I admit, I don’t love the name “Ivy.” But I was curious to learn more about this look, which is how I ended up on a forum. I was drawn into this style’s eclectic expression. There are many takes on it, which resonated with me since I’m not a straight-down-the-middle type person. I like a lot of things.

CM: I don’t think most people would think of “Ivy” style as eclectic.

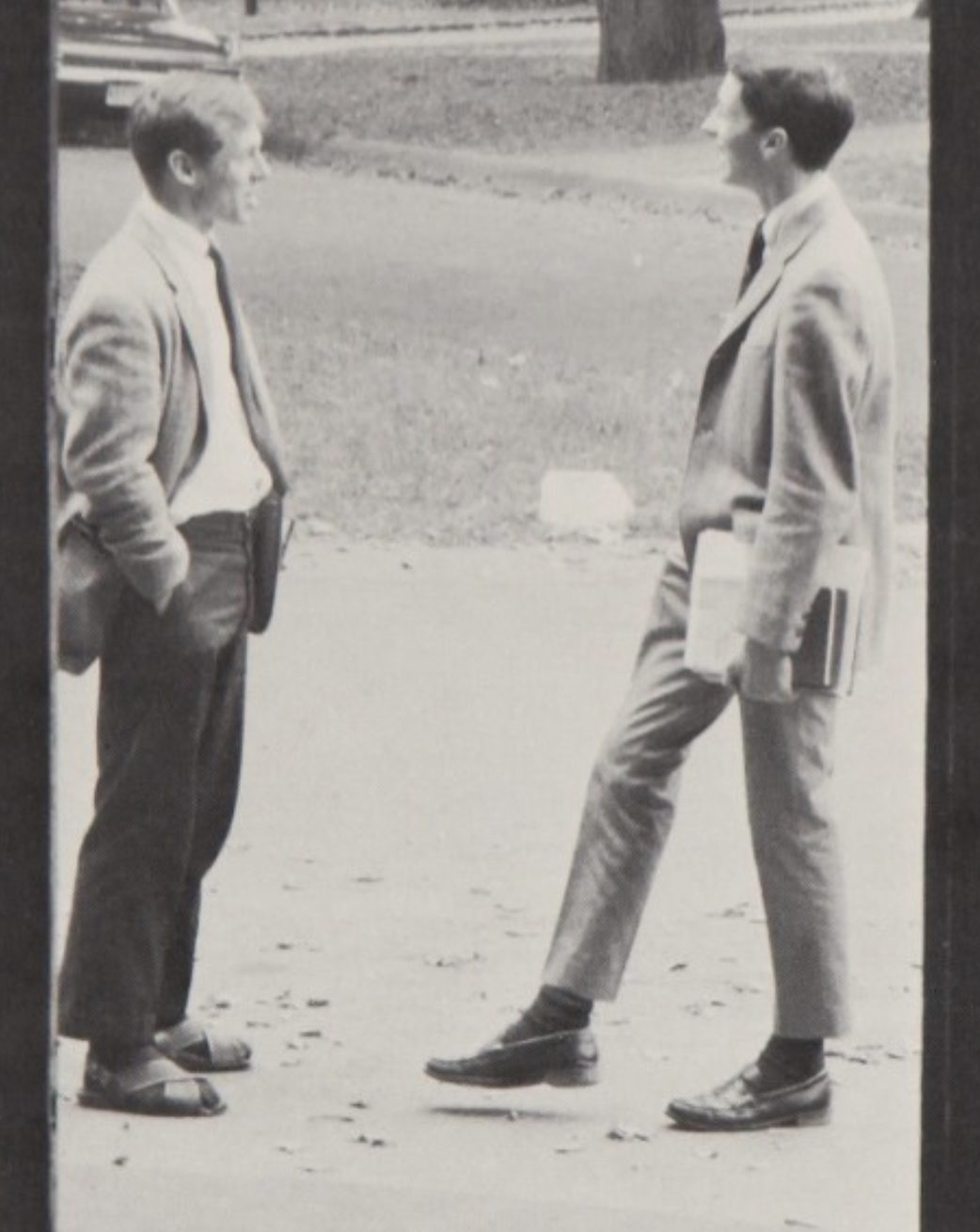

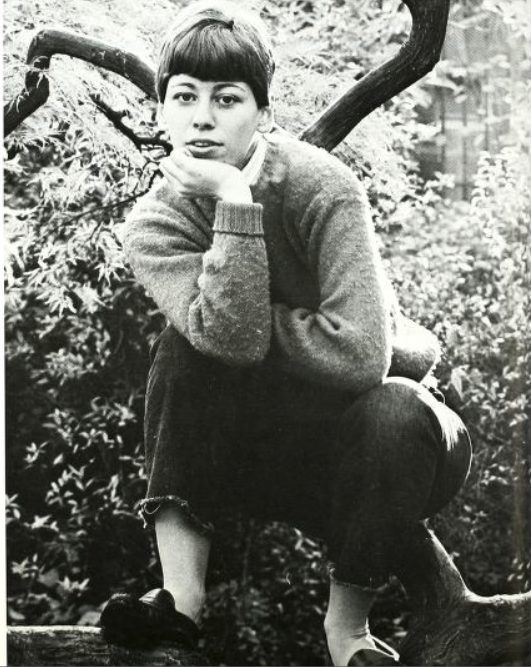

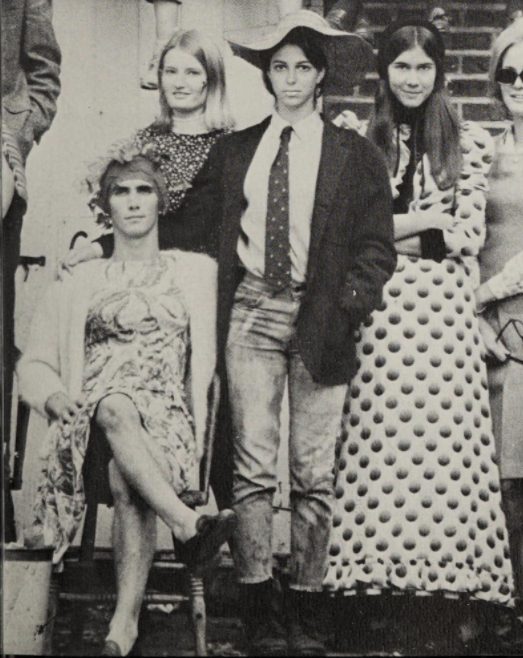

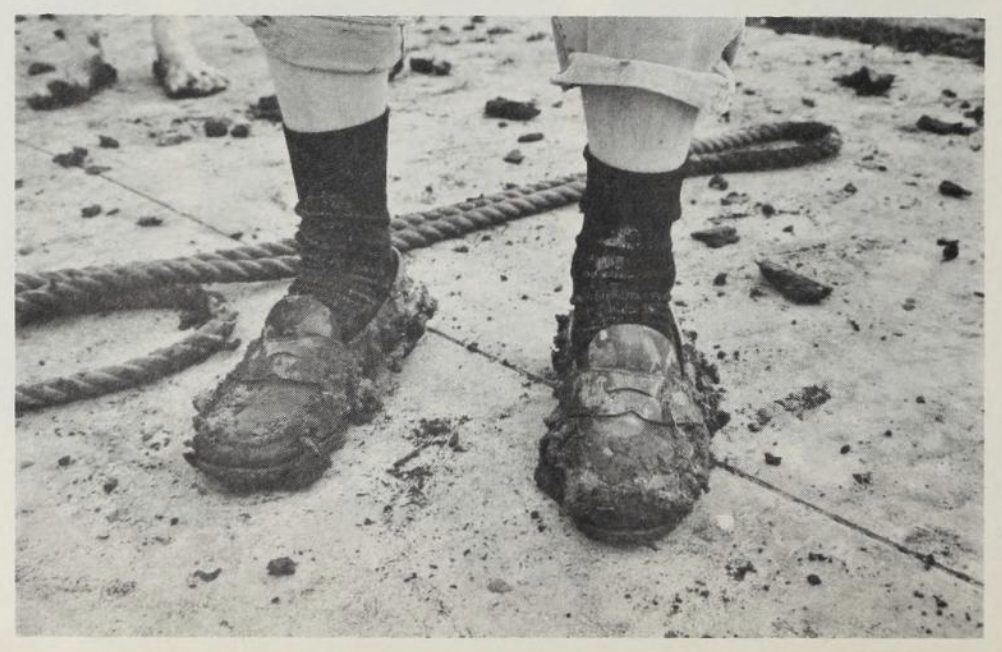

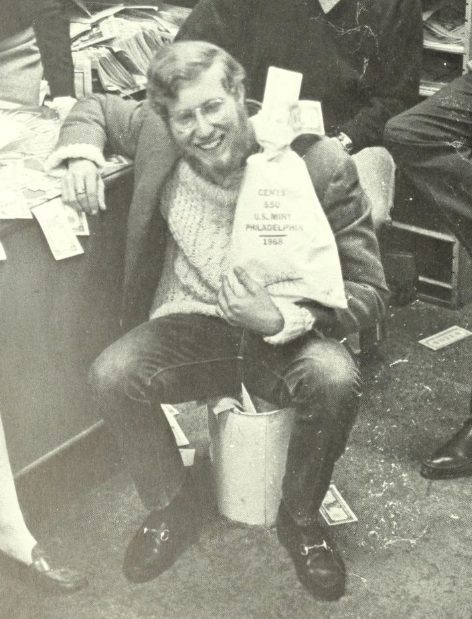

JW: You know, there are only a few things in the “Ivy” canon: penny loafers, three-two sacks, oxford cloth button-downs, and repp ties. I’m not that well-tuned into #menswear or menswear influencers. I’m just within the world of the yearbooks, and the clothes featured are very eclectic. It isn’t all this carefully composed stuff in Apparel Arts or Hollywood images, where everything has its place. People were doing weird things. That’s where this style came from — people doing weird things — and I think that’s forgotten a little bit. That resonates with me much more than the standard narrative about blue blazers, khakis, and loafers.

CM: I suppose this opens up the door to talking about what is the proper term. I don’t love the term “Ivy” myself, and when I look at your Instagram account, both the schools and the style featured seem much broader. I think of it more as American Collegiate style and the casualization of American dress. How do you see the style you are documenting?

JW: This is a very interesting question, as it brings up some thorny issues regarding the style and its associated communities. People often talk about Ivy as a very egalitarian style, which is funny when we call it “Ivy.” I think the clothes are very egalitarian and look good on pretty much anyone. But obviously, today’s prices are not egalitarian. Historically, access to Ivy schools was also not egalitarian. I know that, when I look for yearbooks to take images from, I’m guided by some icky things. If I’m looking at a yearbook from a state school, the chances of it featuring good “Ivy” clothes go down. The same is true of Midwestern schools or schools that have a strong focus on the hard sciences. Those students weren’t coming from these communities, and such clothes may not have served them in the worlds they were about to enter.

CM: You’re pretty outspoken on Instagram when it comes to gatekeeping. I find that perspective refreshing. But how would you describe your relationship with the more problematic aspects of “Ivy?”

JW: There’s a real fetishization of this style as representing elite class culture, something more intellectual and refined. I think many people are drawn to it because they feel like they’re missing refinement and culture either in their own lives or the world around them. Unfortunately, when we talk about culture, refinement, polish, and pedigree, we’re usually talking about some problematic things regarding race and class.

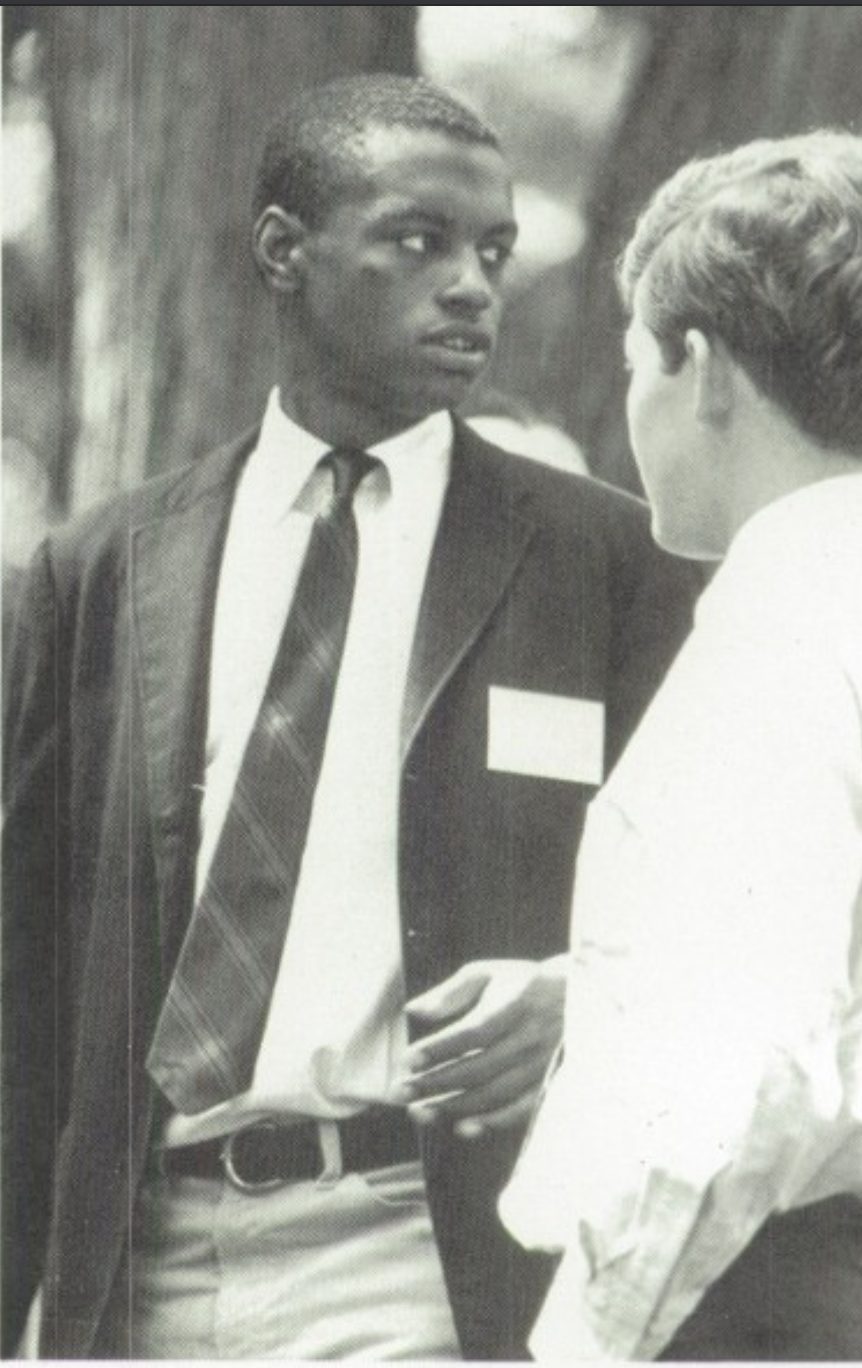

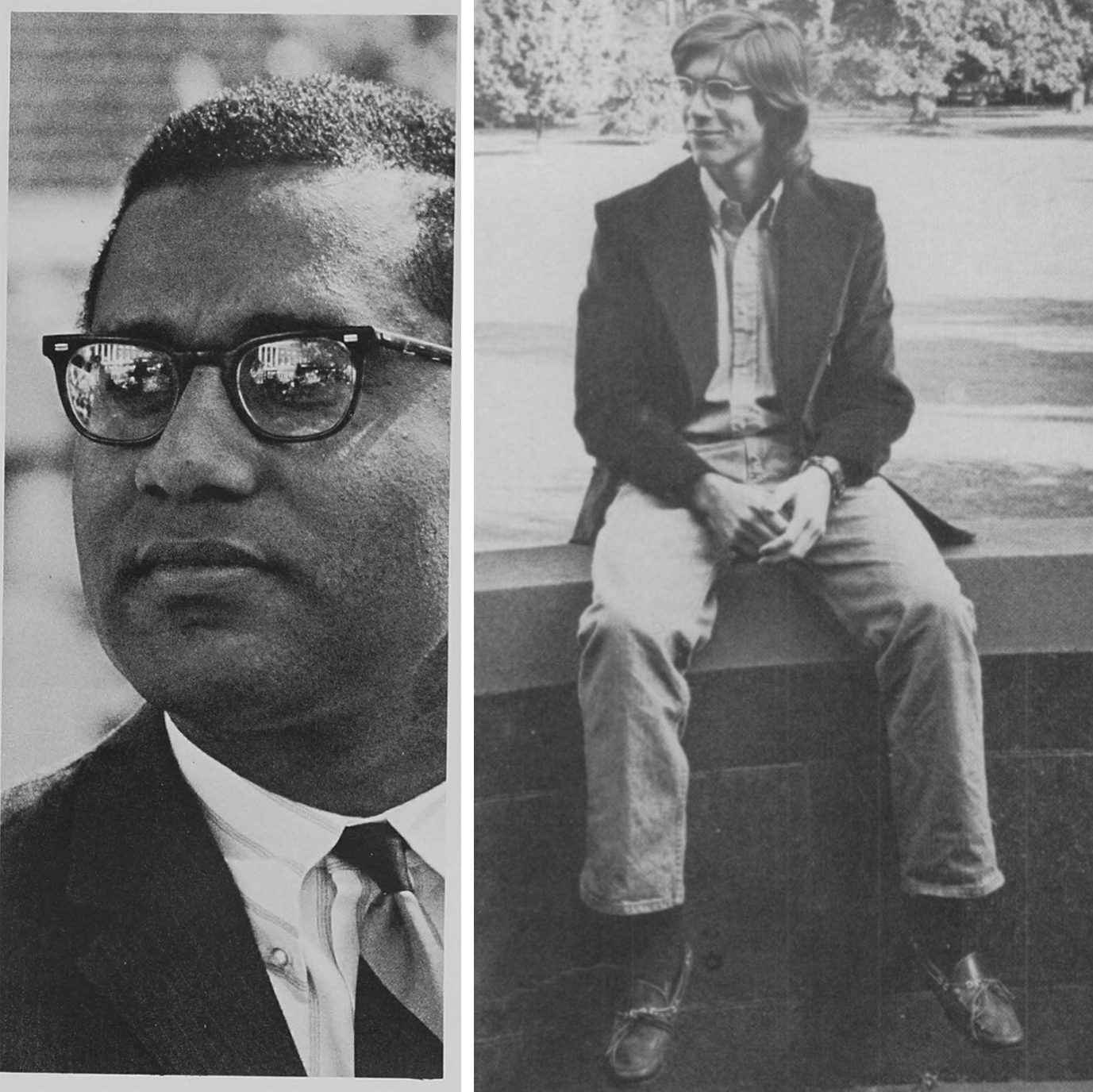

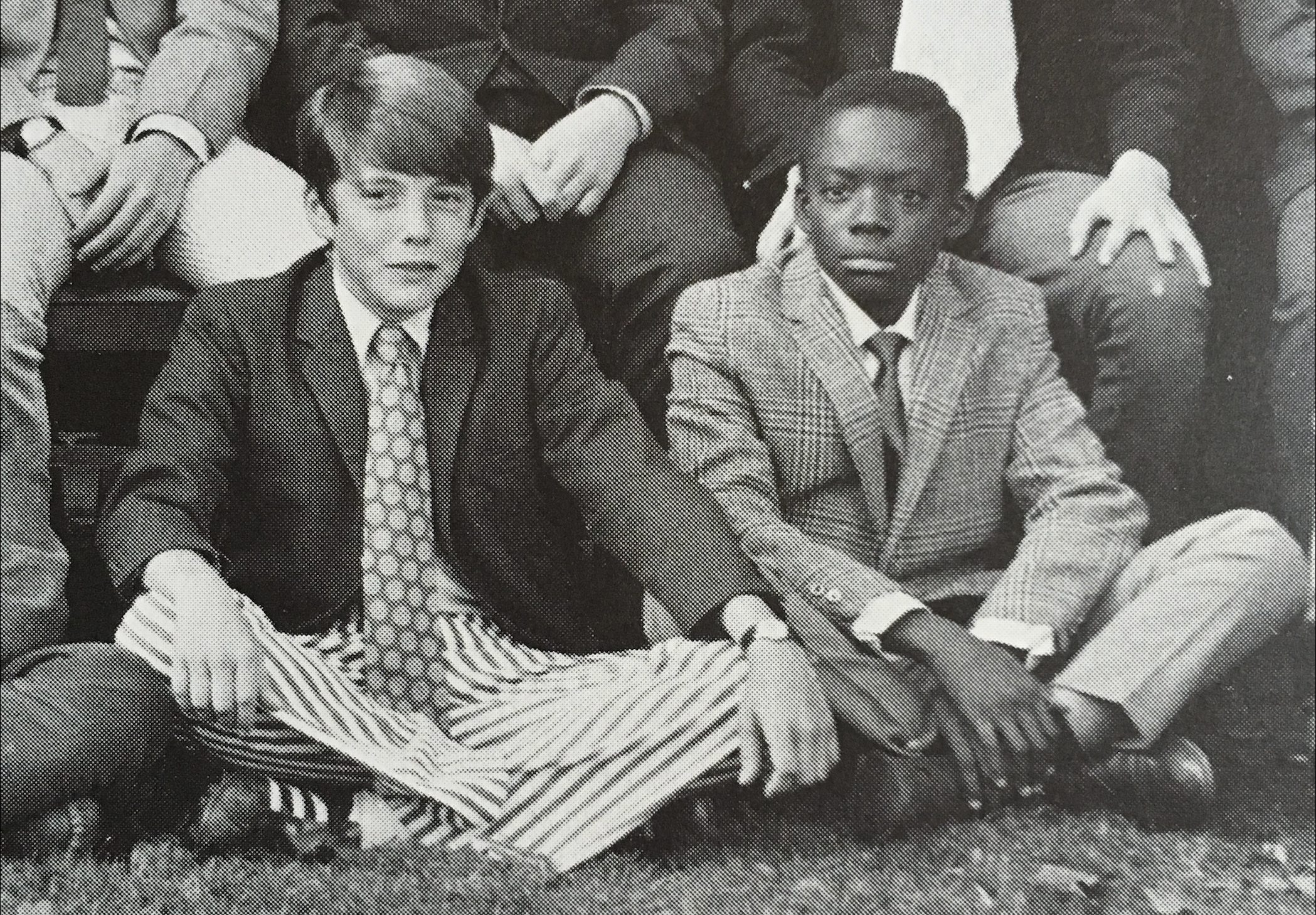

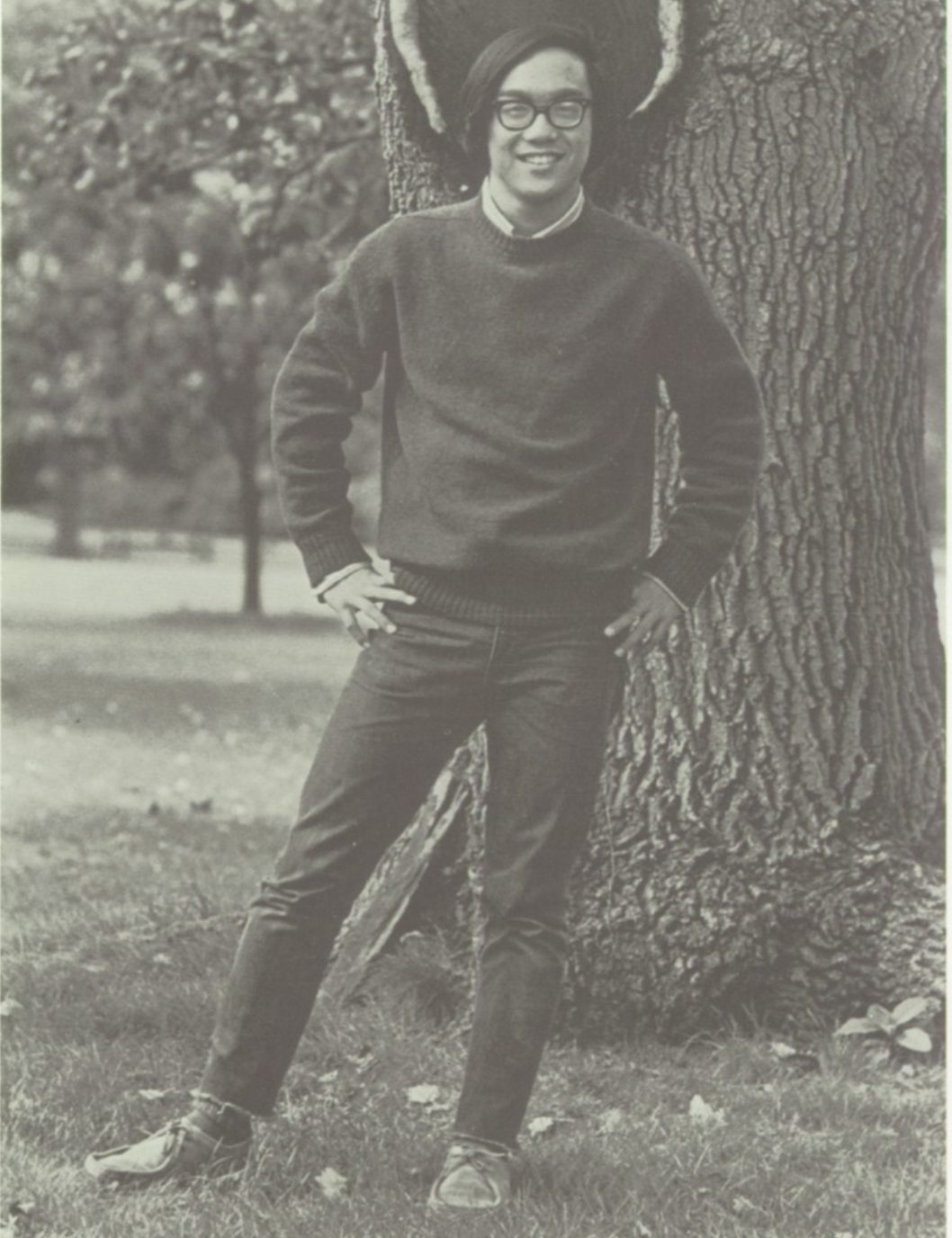

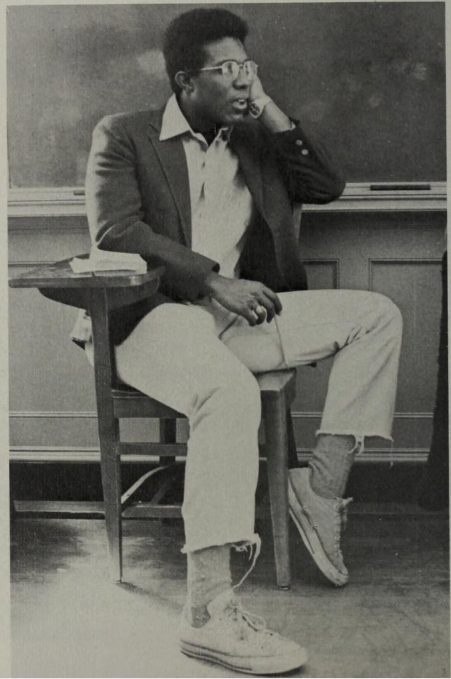

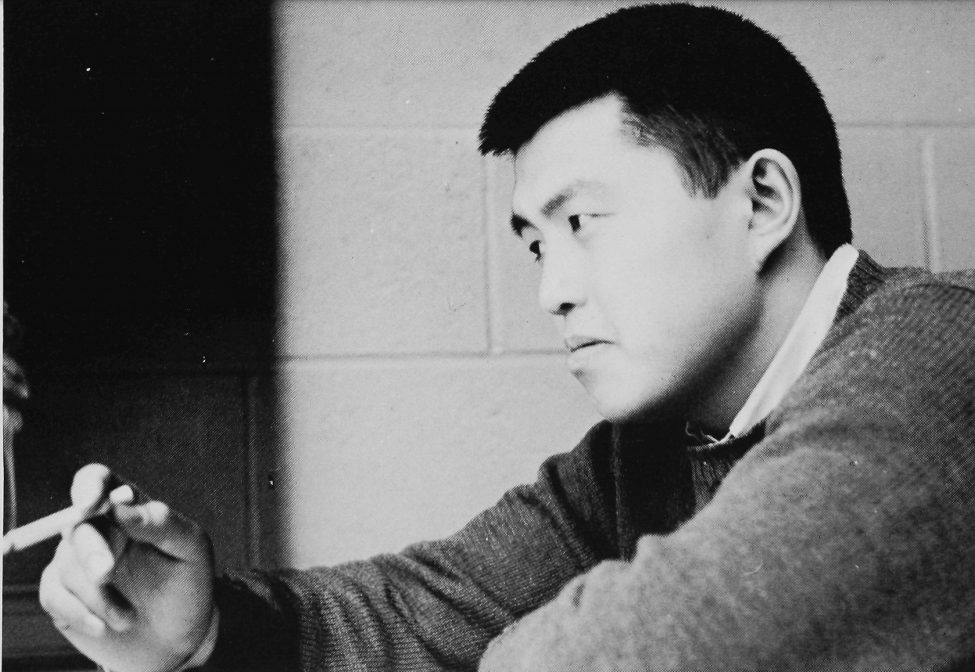

However, when you go into the historical record of yearbooks, you’ll find that narrative doesn’t always reflect what happened on campuses. Schools were very white for a very long time, but then things started to diversify. You just don’t see this record publicized because those pictures don’t fit that Take Ivy narrative. So online culture perpetuates the idea of how this style is supposed to look and what it represents.

I’m an English teacher, and in my field, representation in literature is a big area of discussion. There’s a lot of support now for the idea that students are happier and more successful when they see representations of themselves. Many people in this community like to wring their hands over how no one wears these clothes anymore, but the only way this style will survive is by representing the people who are actually interested in it. The historical reality is that many of these schools were predominately white because of racist structures. But instead of just pursuing historical accuracy, maybe we should try to balance the scales a bit and say, “Hey, here’s this Asian-American student at a prep school who was crushing it.” I’d rather show that person than repost the same photos already shown on a million blogs and sites. It’s about amplifying a part of this style’s history that has been forgotten.

CM: For many people, “Ivy” clothes represent more than just a period in American collegiate dress, it also represents a specific set of conservative American values. As American life has become more politically polarized, far-right politics have increasingly bubbled up in the “only Ivy” community.” Is it possible to separate this look from its associated politics?

JM: When someone is trying to connect these clothes to a particular set of values, they’re often trying to connect them to conservative social values. It’s a bit self-selecting in that regard. If you wear these clothes, you will have some traditional aspects to you. You value the past, history, and to some degree, traditions. The problem comes when people circle the wagons and say, “I’m the last defender of a tradition that others are attacking.” That’s basically every article at Ivy-Syle.com.

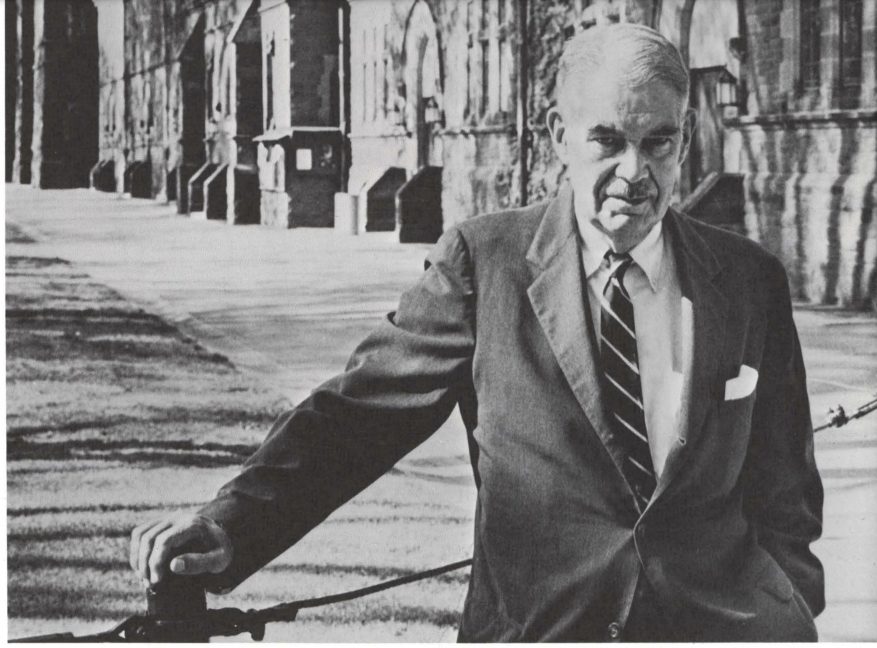

I hope what I’m doing is fighting against that attitude, as these are just clothes. Anyone can wear them, and anyone has worn them. You can hold up as many photos of William F. Buckley as you want and say, “this is the tradition that I’m defending with these clothes.” I can hold up just as many photos of Robert Lowell, Arthur Miller, and Robert F. Kennedy from that same period. There was a time when these clothes were worn by a broad section of society. And as I mentioned, if you show how this used to be a much more diverse and broad field, you can bring in new people today who may have previously felt these clothes don’t represent them.

CM: I think something unique to menswear is how people are continually looking to the past for inspiration. What do you think about the obsession with history, looking at the student archetype and archival material for contemporary style?

JW: It’s useful and dangerous. It’s always going to be helpful to look at what’s come before. It can be something as simple as finding an attitude that you like and bringing that attitude to what you wear today. If you’re looking to the past to ask questions, be curious, and make things fresh today, that’s awesome — I mean, that’s the Ralph Lauren story. The danger comes when you look towards the past for style and feel like you missed out on something. If you’re watching a movie or looking at an advertisement, you have to remember that those things were intentionally designed to make you feel a certain way. It’s easy to look at a piece of media and then suddenly want something — something that will supposedly make you more authentic or recreate a look you love — while not thinking about the emotions intentionally stirred.

CM: Many of the images you find in yearbooks look like they could have been taken a few years ago at some small liberal arts college. Especially when you get into the late 1960s to mid-’70s. It feels like these images are still really relevant today.

JW: I often have that experience, where I’ll come across a photo and feel like it could have been taken yesterday. Some of the outfits are timeless; some are clearly pegged to a period. There are also things in-between. During the 1960s, there were some schools in New Hampshire where many students unexpectedly wore classic cowboy boots. They wore them in postmodern ways, not unlike today, where people play around with conventional rules. And you see this again in the late 1960s and early ’70s, where people felt the power structures weren’t working for them, so they dressed in counter-cultural ways.

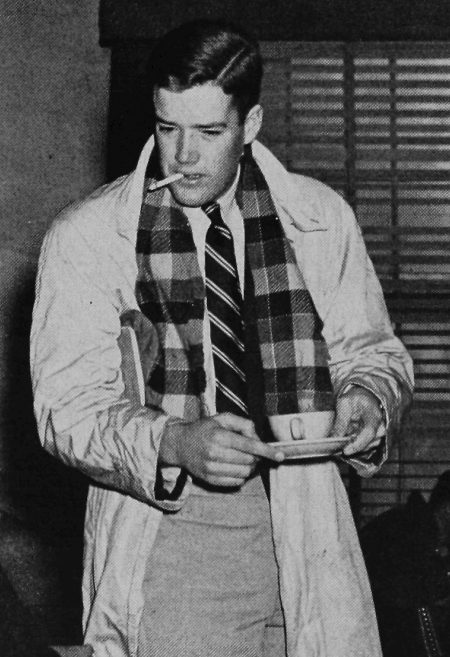

CM: I’m glad you brought that up, as it feels like we’ve been circling this idea of postmodernism in dress. So much of what we’re talking about is our ability to dip in and out of this style at will, and separate dress from its associated values or lifestyle. Do you think “Ivy” or “trad” are thoroughly postmodern at this point?

JW: If you dress “Ivy” or “trad” in 2021, it’s postmodern to some degree because you’re making a conscious decision. Take Tucker Carlson, for instance. Some say his style is natural to him because he went to St. George’s boarding school and later Trinity College. But if you look at the other people in his cohort, they don’t dress like that. Yes, he may have had to follow a dress code while at a boarding school. And yes, he may have grown up in a family that emphasized the importance of wearing certain things. But he also had the same choice as people in his cohort to not buy shirts from Mercer or sport coats from J. Press. But he didn’t; he chose this because it’s a conscious thing to represent something about yourself.

As much as I would like to divorce clothes from values, it’s invariable that people will read things into your clothing choices. This is true if you wear sack suits or cowboy boots. I think the postmodern fluidity comes through context. Our clothing signals are complicated. We each bring something different to those choices — our personality, awareness, and backgrounds — which can change the meaning of even just one item, nevermind the combination of those items in an outfit. That’s what makes “Ivy” style so interesting.

For more of Jonathan’s photos, you can follow him on Instagram at his handle Berkeley_Breathes.