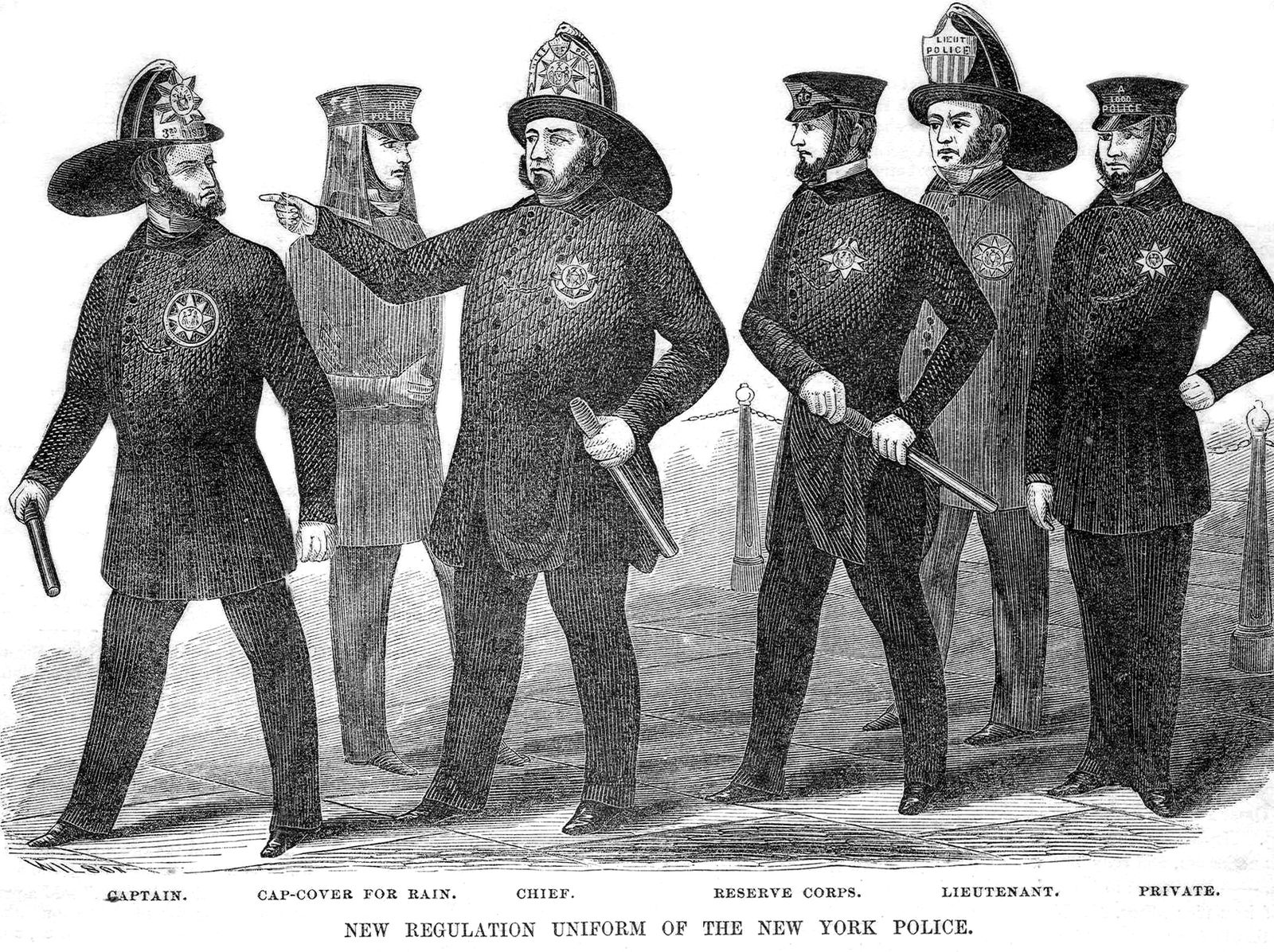

New York police uniforms circa 1854.

In 1974, psychologist Leonard Bickman conducted a behavioral study in Brooklyn. He wanted to test the social power of uniforms. A research assistant donned three different outfits, and asked people on the street to complete small tasks — pick up a piece of litter, step back from the curb at a bus stop, or give a dime to a stranger who needed to pay a parking meter. When the research assistant dressed in a sportcoat and tie, 19 percent did what was asked. When the person dressed in a uniform that resembled a police officer or security guard, 38 percent obeyed. (Bickman also tested a milkman’s uniform, and only 14 percent obeyed. Society just doesn’t respect the milkman.) Wrote Bickman, “A logical analysis of social power indicated that the guard’s power was most likely based on legitimacy.”

Legitimacy is, as they say, doing a lot of work here. Sure, we follow directions from people who dress like guards or police officers, but is it out of respect, or out of fear? The recent protests following the murder of George Floyd demonstrate a more complicated relationship with people in police uniforms, which in their essential elements still call back to the earliest days of modern policing. Black people and people of color were already hyper-aware of the danger of encounters with police in uniform, and damning video evidence and passionate protests have forced a national reckoning with the role of police. On top of that, the police response to the protests has highlighted the creep of military-style uniforms and gear into police departments that clearly changes how police are seen, and maybe even how they act.

The concept of police largely derives from the work of Robert Peel, a British politician who in the early 1800s laid the groundwork for police as an alternative to even more violent mechanisms that had been used to control people. In Peel’s case, he needed to maintain British control of Ireland. Peel subsequently established what is considered the first modern police force in London, colloquially known as peelers or bobbies.

The principles of modern policing broadly attributed to Peel seem reasonable at a glance. The concept of policing by consent asserts that “the power of the police to fulfill their functions and duties is dependent on public approval of their existence, actions and behavior and on their ability to secure and maintain public respect.” Before policing was a profession, law enforcement was carried out by semi-private sheriffs (subject to the whims of who was paying them) or armed militias or armies, who often enforced laws with unsubtle tactics like firing directly on crowds that refused to disperse. Peel’s police intended to more closely align law enforcement with the citizens it ostensibly served.

What does this have to do with clothes? Put This On, at its core, is a site about how you present yourself to the world, about the meaning you express for yourself and others through what you choose to put on your body. What police wear is laden with symbolism and those symbols mean very different things to people who have different relationships with police. And, while putting police in uniform may have practical benefits, uniforms in some cases, and maybe increasingly, emphasize that police are apart from the public.

A Boston police officer in a class B type uniform, with common elements of a police uniform: “bus driver” cap, epaulets, utility belt (often a “Sam Browne” type), identifying patches, and side stripe trousers.

The “thin blue line” concept may be relatively new, but the blue aspect goes all the way back to Peel, whose uniforms were blue to differentiate them from the red-coated British military. The original bobbies wore navy blue tailcoats and were armed, but not heavily — they carried wooden truncheons and handcuffs. England was in the process of industrializing, with many people displaced, jobless, and angry, threatening the established social order. Brooklyn College sociology professor and author Alex S. Vitale has for years linked 21st century frictions between communities and police with these origins: “The main functions of the new police, despite their claims of political neutrality, were to protect property, quell riots, put down strikes and other industrial actions, and produce a disciplined industrial workforce.”

Other cities copied the London model, first in England, then in American cities like New York and Boston, where immigration and industrialization inflamed social tensions. These new forces also largely copied British uniforms. (America added its own awful spin on policing; early police forces in rural areas and the South were rooted in slave patrols, charged with hunting down enslaved people and brutal prevention of organizing or revolts.)

Peel’s police and the forces that followed them were, on paper, expected to enforce the law with the consent and cooperation of the public to which they belonged. But police uniforms — from 19th-century tailcoats to present-day starched shirts and epaulets — reflect their position between the military and the public. And over time they’ve shifted one way or the other depending on how police would like to be perceived.

On a basic level, police officers wear uniforms so they can be recognized. People who may need help can find them, and people who might commit crimes might be deterred by seeing them. Departmental insignia and badges with ID numbers also increase accountability. Without really thinking about it, you probably know what a police uniform looks like, and may even quickly differentiate a police uniform from private security. Depending on your perspective, the uniform confers legitimacy — this person has been trusted with public safety, my safety — or fear — this person is dangerous to me.

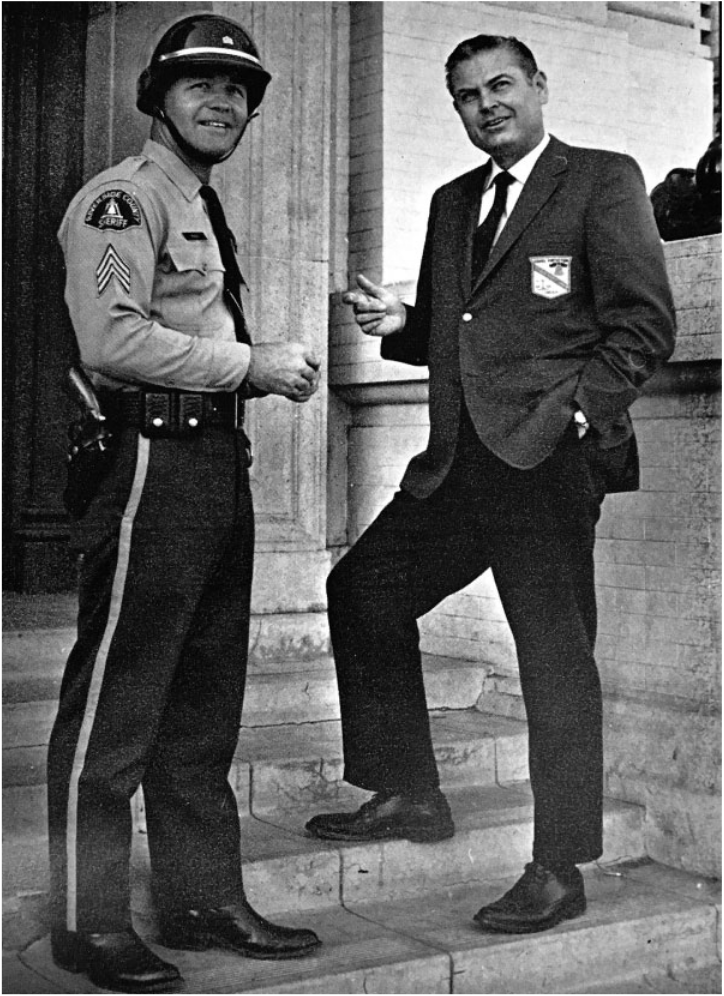

Riverside Sheriff’s Department, 1970s. The man on the right is in an experimental, demilitarized uniform.

Famously, a number of police departments in the 1960s and 1970s attempted a jacket-and-tie uniform in order to look less like paramilitary groups and more like community-minded professionals, following years of erosion of public trust. In Menlo Park, California, data showed a decrease in violence both against and by police officers in the years after switching to a blazer-based uniform. But the trend didn’t last, and the department also implemented other reforms, so it’s hard to say whether it was the blazers that made the difference. In any case, these departments eventually reverted to the peaked caps and Sam Browne belts of traditional, paramilitary dress. Other departments have tried softer tactics without changing the uniform overall — encouraging officers to take off their hats and sunglasses, make eye contact, greet people.

Today’s American police uniforms are split into different classes — generally A and B, and sometimes C, broadly in order of formality. Class A uniforms might include items like a tie or a wool jacket, with formal, creased trousers. Class B might still include a starched shirt, but worn with an open collar, and less flair. Dating back to Peel’s days, by design police departments have been governed by local governments and have not been a united national force, and one of the effects is that uniforms differ from department to department. They’re not always blue — some departments wear black, some gray — white is uncommon in the United States but not unheard of.

These are the familiar uniforms of police — how you might see a police officer in a 1960s cop show, or how a kid might draw one in uniform. More and more, though, police have adopted more “tactical” gear, which can contribute to negative perceptions in the communities they police. In 2018, two law professors, Eliav Lieblich and Adam Shinar, published an article on the creep of militarization into police departments.

There was a time when there was crime without a war on crime; a drug problem without a war on drugs. The war metaphor came about in the wake of World War II, when leaders sought to rally public support to solve social problems. The “war on crime” was coined by President Johnson in 1966, whereas the “war on drugs” began during the Nixon administration. Nixon called drugs “public enemy number one,” equating them with “foreign troops on our shores.”

Like military uniforms, police uniforms have long included sewn-in creases, and designated places for badges, pins, awards, or other insignia. In the years following 9/11, especially, police departments moved strongly toward a military presentation. Tactical elements like BDU pants derive from the American military battle dress uniform. More and more departments require body armor (80% in 2013, according to the National Institute of Justice), which may be practical in what is a potentially dangerous job but also serves to make officers look more like soldiers. Wearing such gear sends a very different message than a jacket and tie — people can reasonably infer police officers are prepared not for patrol, but for combat.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CA_UtnNHqNZ/

Following the 2014 killing of Michael Brown and subsequent protests, where police were seen traveling in Humvees and MRAPs (mine-resistant ambush-protected vehicles), heavily armed, there was a public backlash against equipping local police officers with gear designed, and previously reserved, for fighting wars. Programs that transferred military-grade, surplus equipment to local law enforcement were curtailed. But images from the last few weeks have shown police in just such gear, plus harder-to-identify law enforcement officers, undercutting the accountability factor of the badge and uniform.

Lieblich and Shinar made an argument that calls back to Peel’s principles of policing.

The real problem with police militarization is not that it brings about more violence or abuse of authority — though that may very well happen — but that it is based on a presumption of the citizen as a threat … A presumption of threat assumes that citizens, usually from marginalized communities, pose a threat of such caliber that might require the use of extreme violence.

It may cliche to say dress for the job you want, but as we consider the limits of the jobs we really want the police to do, we should consider how we dress them for it.